It's All in the Joinery

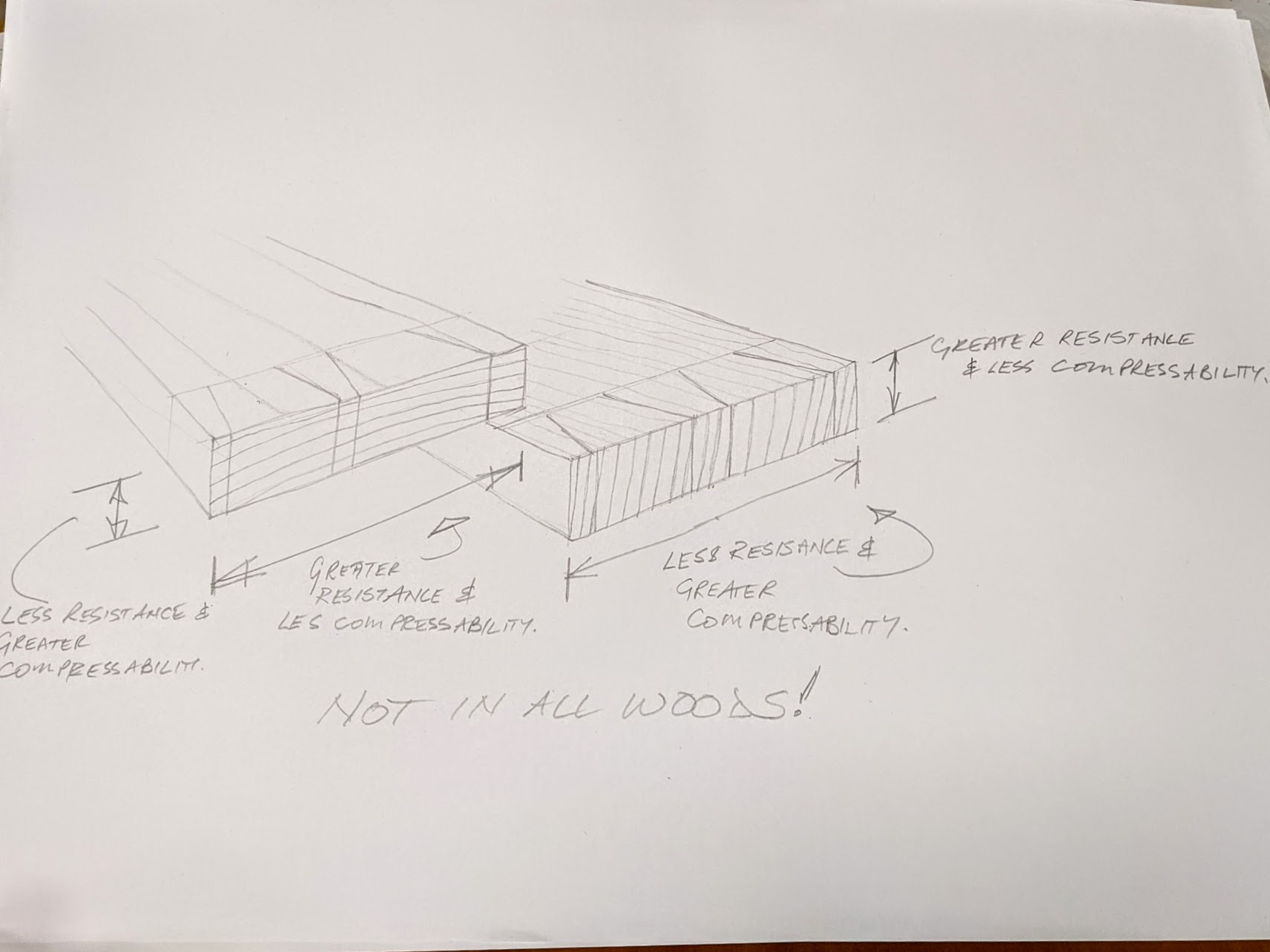

It's all too easy to take accuracy for granted, especially when you've been cutting them for so long. Many people think that it takes my fifty-five years in the saddle to become competent but that's not at all true. Fifty-five years just leaves you with fewer excuses. Reality is I have simply come to know my woods more than most, and by more, I mean differently. And that then is mostly because of my working the woods primarily with hand tools. I know what compresses and where and why and then too by how much. Different woods compress differently and then too even within the species there is great contrast too. This knowledge advantages me more than anything and it is this knowledge that can be explained to some degree but gain comes only from experience. It's at the bench where we hand toolists learn the most about our different woods and their workings, their properties, characteristics, strengths and weaknesses and so on. We hand toolists may not work always by dead-on fits even though we can and often do. By that, I mean that we may well choose not to. No, we often make those minute tolerances that come from our experience as developed intuition. We take one shaving less to leave something a thou' fat. Grain orientation is the critical factor and so too the grain configurations that come in the wood from its various positions when it was alive and then simply remaining within the growing the tree.

A branch weighing two tons extends ten meters out from the tree stem. With nothing but the interlocking grain to hold it there something happens to the wood and it shows mainly at the bench in the cutting of a joint or the planing of it. Chop a mortise in a knot or the intersection of the crotch grain and you experience a wide range of resistance factors ranging anywhere between pure brittleness to just plain out and out, wiry, stubborn, awkwardness.

Dead knots, live knots, these are all too familiar as are areas surrounding crotch-grain and such. There is then short grain too, where the grain changes and seems to be standing up in its own swirl of contrariness to the long axis you are working. The mortise in the middle of areas like this runs contrary to what you expect. It's a pain. And whereas it may be hidden by the tenon shoulders when it does, if it's a through tenon it may well be too late and the visible edges to the corner rim of the exposed outer face might end up splintered off.

As a machinist, I always simply dialed in the exact sizes I needed. It was a zero-tolerance requirement of industry. The chisel mortiser delivered perfect symmetry every time with no possibility of variance. The tenon from the tenoner did the same. Slip the tenon into the mortise and it was nigh on a frictionless fit. In the industrial world that was what might be wanted. A thousand joints in a day made up a hundred doors or window frame sashes. The boss (I was self-employed) was happy with production. Making a hundred thousand walking canes with mortise and tenon handles needed mass production methods too. That's what I left behind. When I make a coffee table from oak or cherry, a dining chair from mesquite, perhaps a dining table, I find myself off the conveyor belt and then shunning it for lifestyling of choice. When I offer the corner of the tenon to the mortise my senses totally engage for the feedback I get in sensing compression and compressibility. It's this communication my work now demands constantly and indeed I truly want it. It's this that I want to interact with. Too much pressure? There's the crack sound. I stop, ease, pare cut and refit. Too much and the joint is sloppy. A little pressure here and there and lo, there it is, what I see as that perfect joint. That's my aim in the working of the wood. Not one relying only on glue alone but one relying on a combination of both mild levels of compression and then glue too and then perhaps a draw bore pin or a pair of wedges dovetailing all together forever. Somehow its the inaccuracy of accuracy that appeals. The draw bore seems at first clumsy, but then you see how the wood has yielded, bent and compressed in its elasticity to conform all parts in one common goal--to stay together. It is so very permanent, you see. My accuracy is to understand by how much I should offset the hole in this piece or section over that one. Too much one way results in a negative in the other way. My goal is to sense within the mortise just how much tension there is between one part to the other.

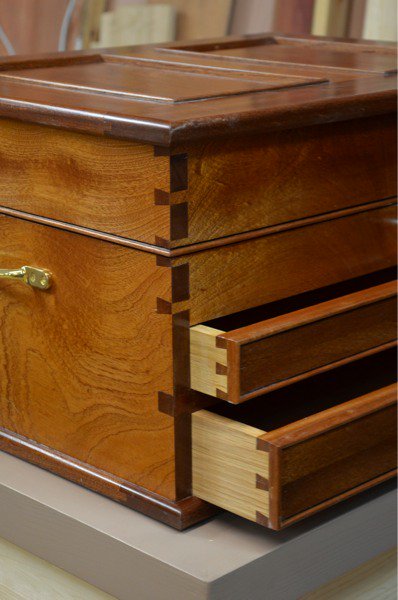

When it comes to my dovetails there are a dozen variables of which I may only know half a dozen. One day I pick my wood and I learn something completely different and new. This is wood. This is why I love my working of wood by using hand tools and my senses. For me, it is the unpredictability that results in challenging work. I do not want a guaranteed outcome of predictability. I will never make a thousand tenons in a row again in my life and nor will I ever want to again. I suggest you do not go down that pathway either. But, as I have written often, sometimes you have to see what something is not to see what is. To me, mass making methods led me to feel I was just button-pushing, stacking and loading and pushing in and taking off. By far one of the dullest, mind-numbing periods of my life. But more than that, it was soulless and soul-destroying enough to help me see both what I did not want and then what I valued the most. My handwork. Now I want to be careful here because I do like machines. There is nothing wrong with them, but in my world, the key to being well is finding some degree of balance that matches you and your particular situation as an individual. I feel I have found my balance with the use of my bandsaw.

So my dovetails are for me high-demand. They require my total attention and no part of my sensing can ever be diverted to allow another distraction mid-flow. My inner easings reduce certain frictions but disallow over tolerances. I don't use gap-filling expanding glues as happens extensively in some courts. Oak dovetails are sized differently to cherry ones and pine ones vary from spruce. It will take you a lifetime, but oh, what a lifetime of discovery.

Comments ()