Framings and Panels

Framing, panelling and book-matching embraces the reality that we must have wide expanses of wood and that that expanse must be either free to move 'float', or be semi constrained within some kind of frame. Through the centuries we have learned what that takes. We've refined the methodology through our understanding or at least acceptance of a couple of key facts; in some cases a wood and panels, especially panels, must be allowed to move or to 'float' as we call it, or be constrained. Like the weather, we have learned to work with it and not against it.

Tabletops are a good example of 'floating' panels. Most often we anchor them to an under frame on legs, posts or stanchions depending on the design. Turnbuttons are the most commonly used and these little blocks attached to the underside of a tabletop pull the top the the top rail while still allowing the panel to expand and contract at will. Why is that important? Wood will often give somewhere if it's prevented from shrinking.and the give results in a crack or series of cracks and especially does this happen when the wood itself is unevenly dry. Uneven dryness can occur after drying so the ends can absorb and release moisture at the 'open' end of tabletops through the endgrain pores and expand (result below). Conversely they can release moisture and dry more than the centre section which may be unable to release moisture at the same rate of release. this very often results in splitting or, if panels are glue up as a lamination, separation along the joint lines.

Whereas if you shrink the wood to its lowest level by additional placement within a controlled heat source and then frame it, provided the frame has the strength in wood and joint, the frame can readily constrain the panel to prevent expansion. If the panel is so reduced then it is unlikely to shrink less and even if it does it will be so minimal not to cause splitting as the wood itself does have some 'elasticity' or stretch within the fibres. If the panel is too high in moisture it will invariably continue to move by some degree throughout its life - breathe in, breathe out!

Panels of wide solid wood must generally be allowed to expand and contract as they take in and release moisture that comes from any water source be that steam, spillage, rain or the atmosphere surrounding it. Any heat source apart from steam causes the wood to first expand as any moisture in the wood's internal fibres expands until the temperature then forces the water out by the pressure expansion causes. From then the wood continues to release its moisture and the internal fibres continue to shrink until the fibres reach equilibrium with the surrounding atmosphere. Consider a panel to be anything from a tabletop of any width on through framed-in panels held in a channelled frames, things like a door, hatch, cabinet panelling and wainscotting. Although today these panels are more likely to be made from man-made or engineered sheets like plywood and MDF, many of us prefer the look, sound and feel solid wood gives to us.

One of the great advantages to panels is the ability to create wider panels from narrower stock. Above you see two pieces slabbed off from 2 1/2" stock to create a five inch panel. If you rip down thicker, four inch material like a two by four (below) then you can create a more symmetrical book matched panel 7-8" wide that's balanced in colour, shade, and grain configuration. This gives you great control in establishing a balance approach in a project. If you have a thick enough piece you can gain repeat facings either as solid sections or as veneers to be applied to a sub-wood. Whereas many 'disconnected' experts often say veneers are used to save wood and the forests, that is only true in part and in the realms of mass making where its done to hide the ugly innards of MDF and pressed fibreboard. In its origin that was not the case and neither is it in the case of many makers today. No. We mainly want to control colour and grain configuration to give balance and uniqueness to our work. That is the same as those in times past who often veneered fantastic grain onto sub-wood of the same species but a more plain variety.

The methods we rely on mostly are unframed panels as in the tabletops, breadboard ends and then framed panels that can be single frames, as in top and bottom rail and two stiles, or multiple-opening frames as in wainscotting, display panels as in notice boards and the like with signwriting. Think panels with team names as in years of cup winners and such.

Breadboard ends rely on more complicated and therefore additional work that might well make the project prohibitively costly in time, but, also, in many projects they are unnecessary. Solid panels, unframed, as in tabletops can expand or contract by sizeable amounts ranging from up to or down by 1/2", depending on the original point of expanse.

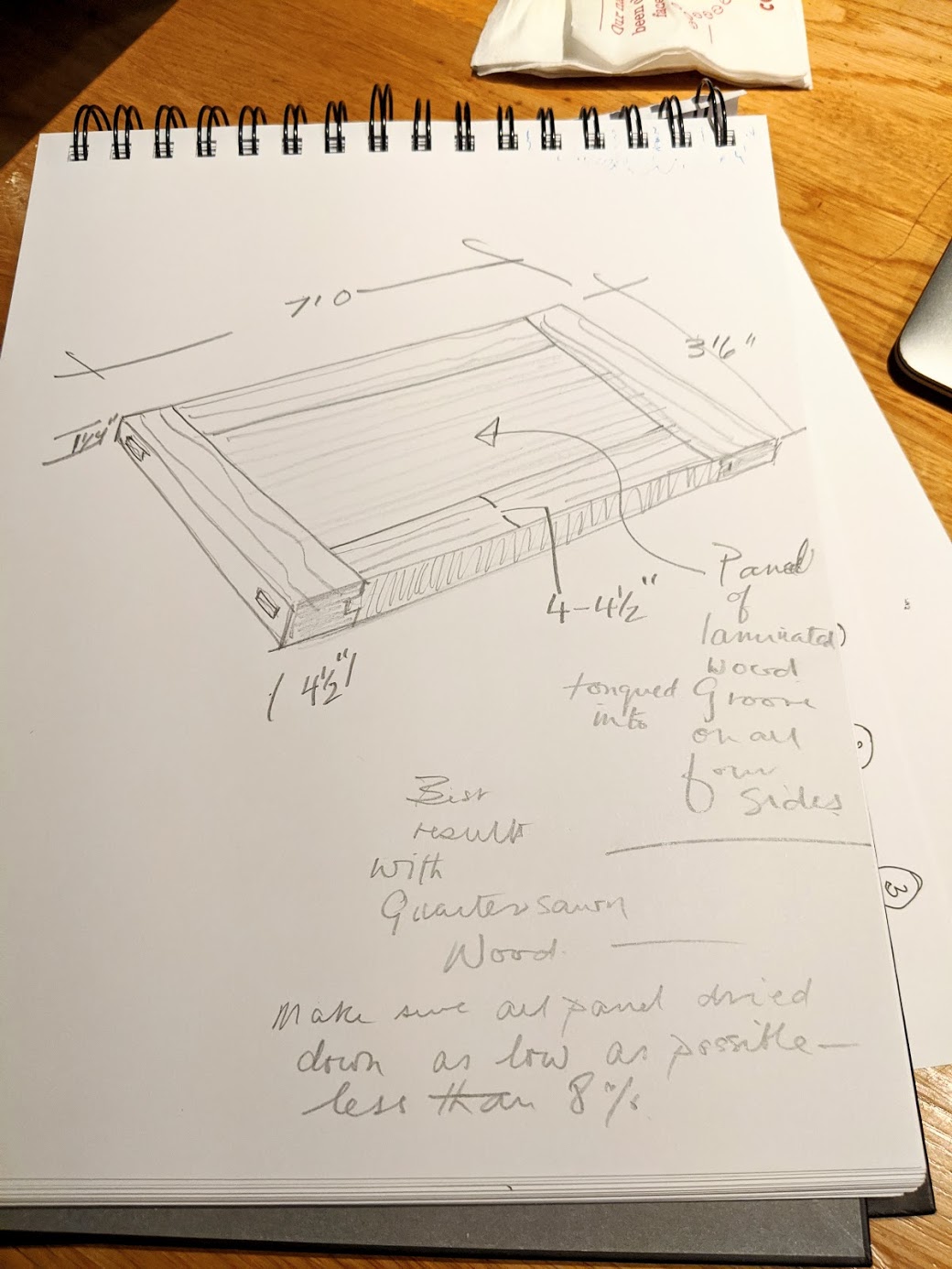

Adding breadboard ends is an option for constraining the mid section of wood by capping what is usually the ends of the panel to keep tabletops from undulating because of grain orientation but, well, it's complicated, as they say. I have had great success with the offering in the drawing below however but the method does rely on dried down panels fitted within the frame. Down to 5-7% would be good I would say though I cant recall measuring with a meter so much as by weight. To get them down that low means a dehumidified atmosphere and the dry heat you get from radiators, underfloor heating and such. This is best done slowly and with moderate heat increases.

Comments ()