Finishing Your Wood

It's the number one fear for most woodworkers, a little agitated skip from foot to foot as you toss the rag from hand to hand. I understand this. Mostly it's because it's an area of work that is indeed the least predictable for a guaranteed outcome and especially if your read up on the subject or ask other woodworkers. Ask ten woodworkers which finish to use and you'l get ten different answers. I think that that is why people in general plumb for any kind of ragged-on oil finish that's wiped on, left for a few minutes and then wiped off vigorously to minimise runs and gummy puddles of unevenness.

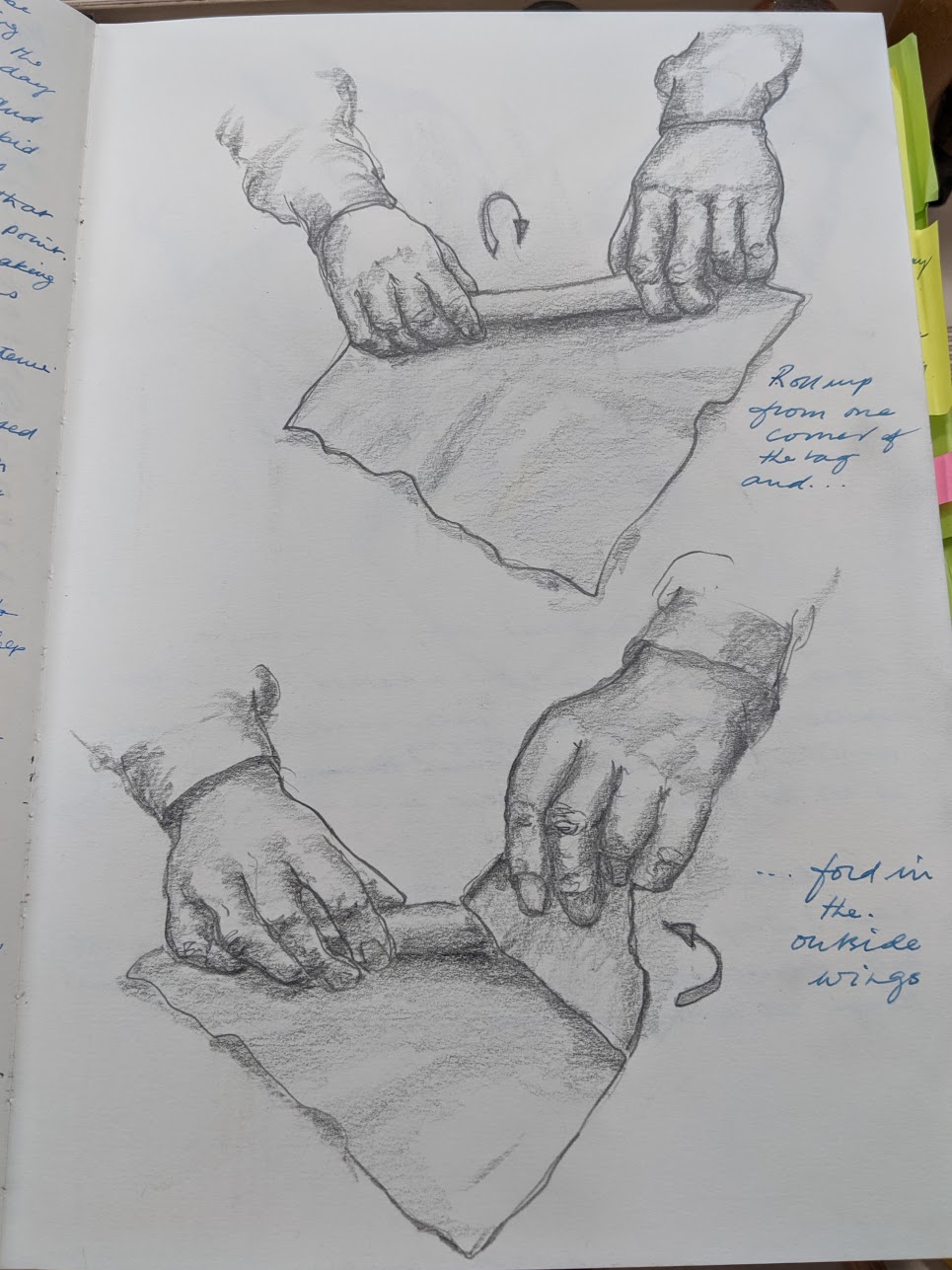

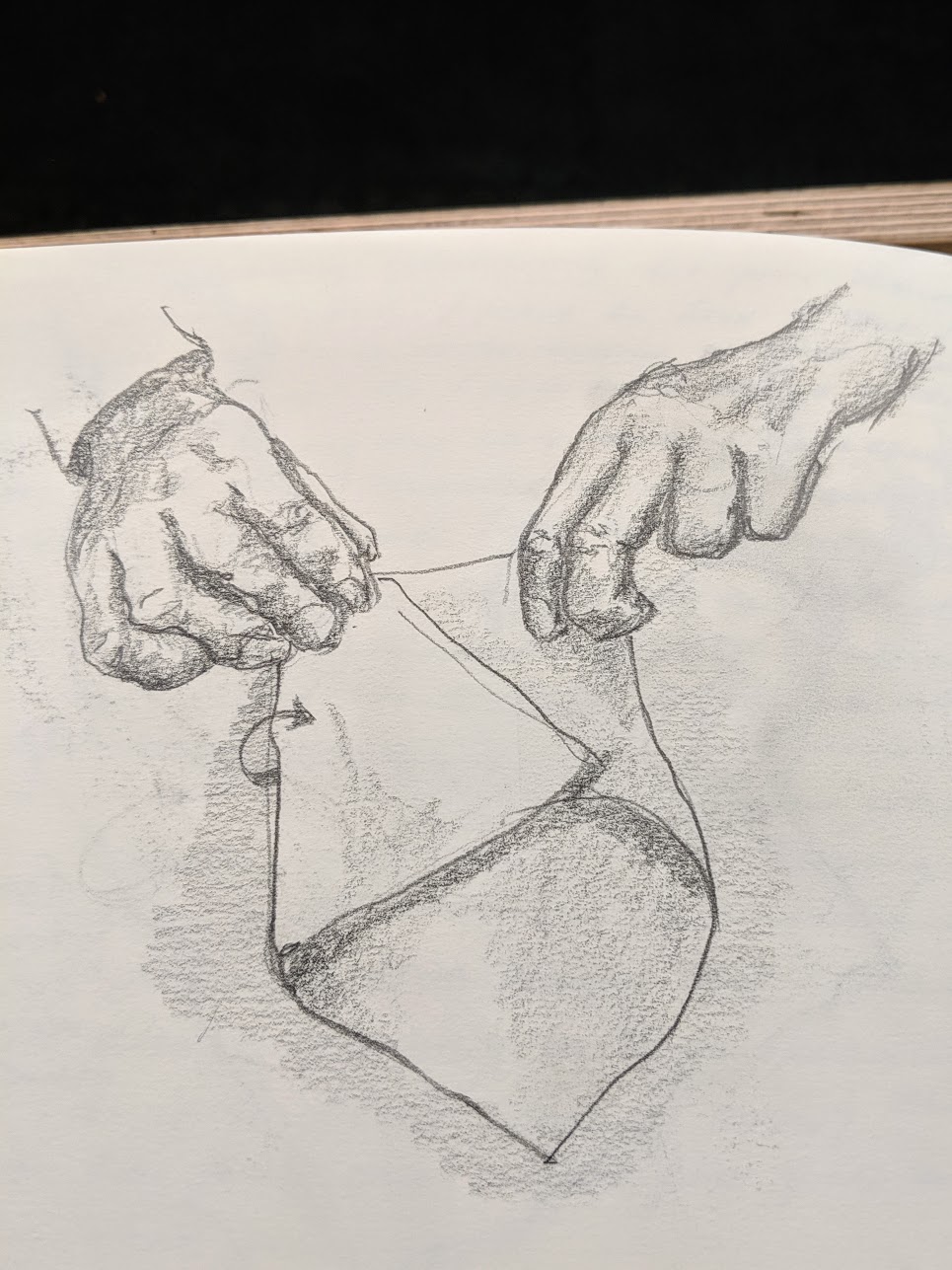

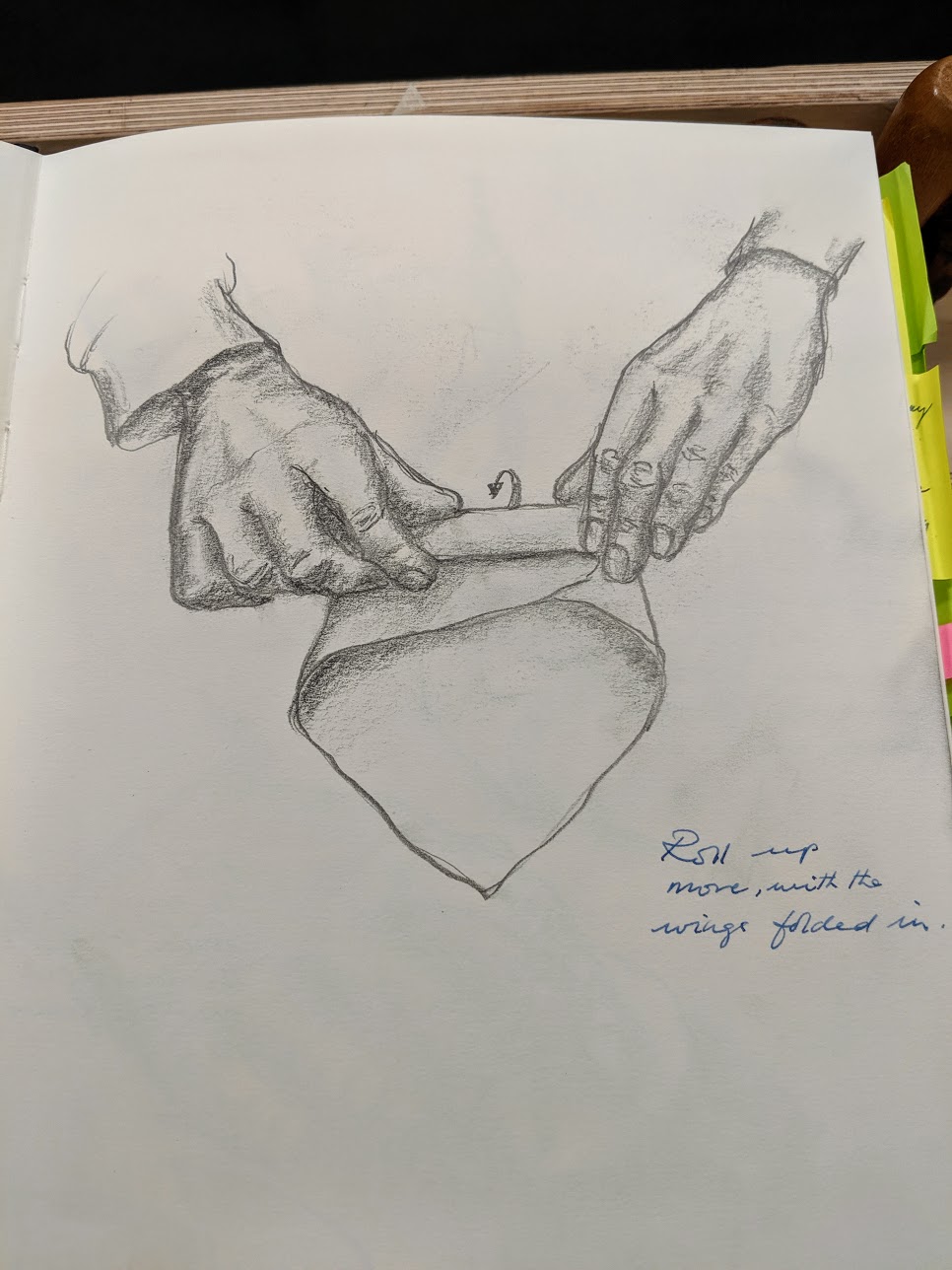

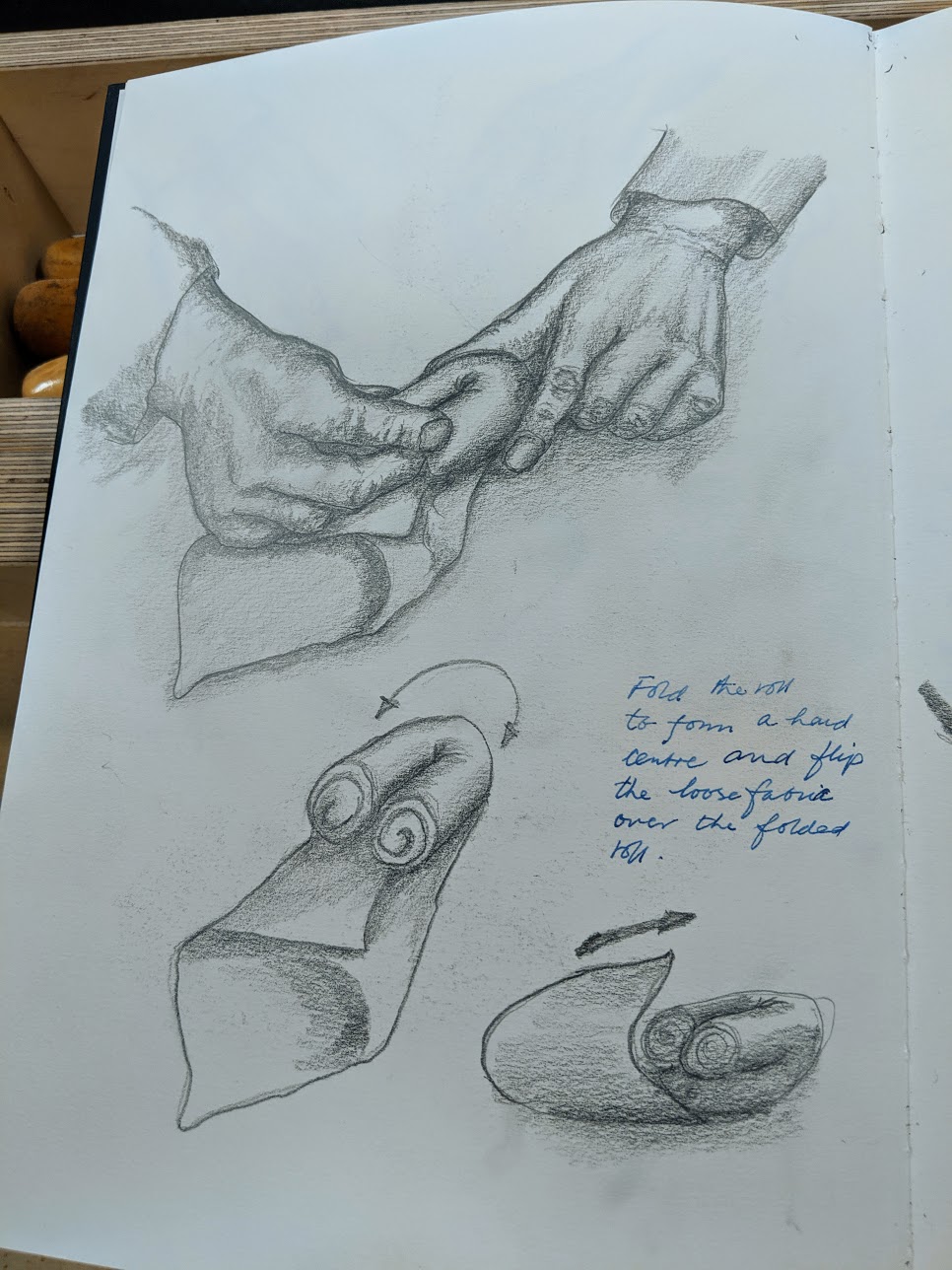

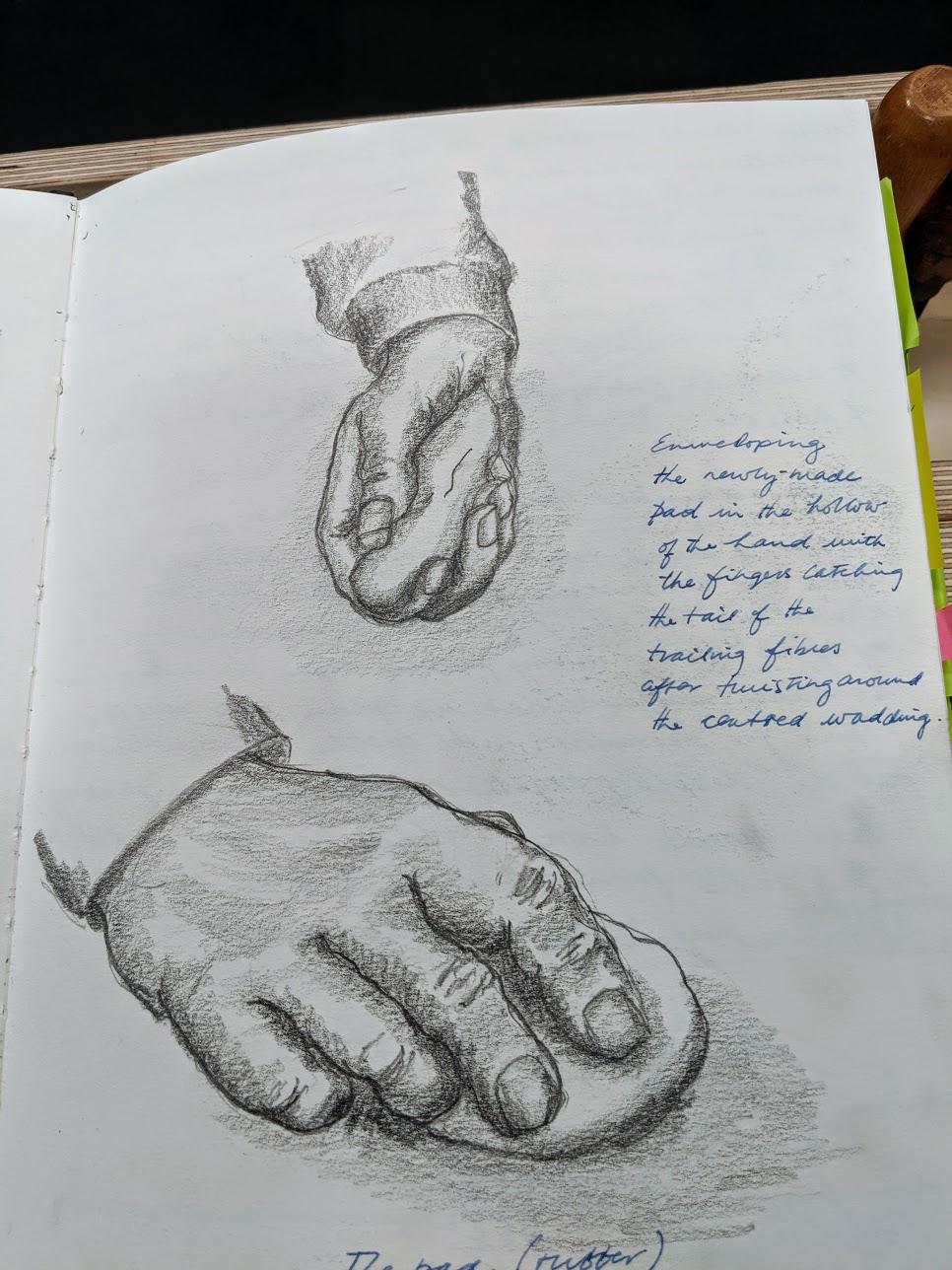

Hand rubbed is often used a bit disingenuously by many if not all makers. They take advantage of the ignorance of their customers as they extolling 'hand-rubbed' as the final highly skilled refinement of the project. The artisan usually presents hand rubbed as a method paralleling something like French polishing work because, well, both are indeed applied by the hand rubbing a cloth over the surface. But even here I should point out the difference. The application of oil is simply dipping the clutched rag into oil and applying it to the surface and spreading it out. On the other hand the well-proven method for applying shellac as in French polishing is uniquely different. In this case the cloth is folded in a very specific way to wrap within it a ball of cotton wool. The wool itself is charged with small amounts of shellac repeatedly and squeezed through the cloth by the forefinger and thumb at the fore area and the three fingers behind. This applies ultra thin measures of shellac to the surface being treated and layer after after layer of thinness results in the depth and chatoyancy true French polishing is known for.

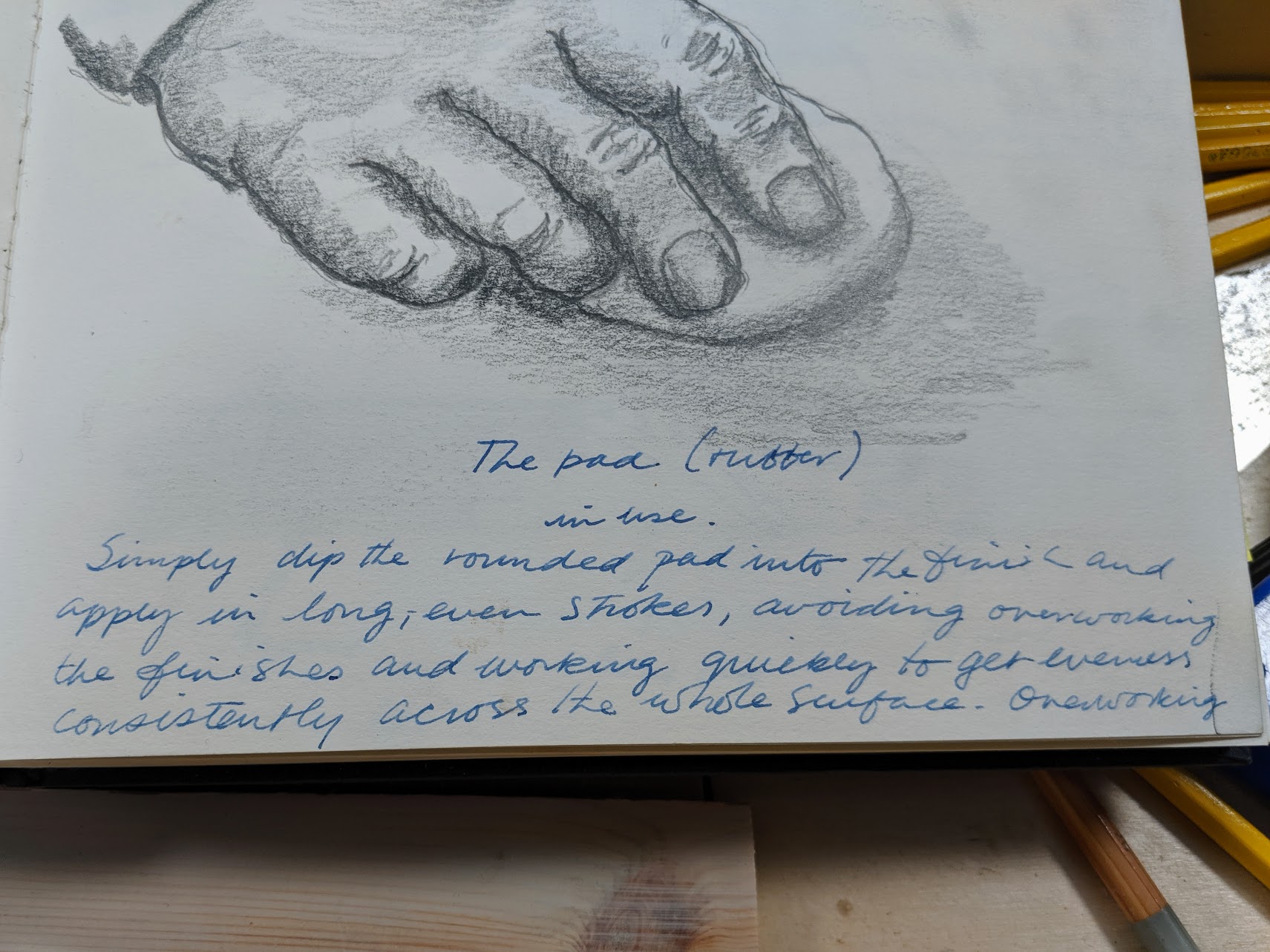

Below is a simple pad I use for french polishing that works without cotton wool stuffing that can be dipped rather than internally loaded with shellac.

Notes and drawings from my April-August 2010 woodworking journal:

So in reality, the two areas are as different as chalk and cheese. One, the French polishing, is indeed a finely crafted art form that takes a long time to master in all of its many diverse ways of treating the expansive range of pieces it's used on. All oils on the other hand require about the same effort as wiping down a cafe table or a kitchen countertop. That being the case, why should you fear it?

A contrast I saw between my living and working in the USA and then Europe were two things in general. In the USA I noticed the massive use of wood stain to change the colour say of one light wood to make it resemble a more expensive dark wood. This seems much less likely and not to be the case in Europe and indeed Britain. I think that that is due more to the influence of Scandinavian makers both in the mass-made realms and then to in the realms of individual designer makers. Another predominant difference is the use of classic mouldings to trim out corners, soften outer edges to surface mounted doors and such. The highly ubiquitous power router with its routerphile following is on the constant lookout for something to use their screaming machine on.

The development of wood finishes as all in one topcoat and stain products are available in different forms by various manufacturers. Polyurethanes are available as wipe-on, brushable or padable types or as a sprayed on finish also. These are the easiest finishes to apply and are easily touched up in the event of damage. The main advantage of these finishes is the open time you have in applying them and then their durability and ease of repair. Looking for finishes can be confusing but all of them can be applied differently and a little experimentation will help you to develop a better understanding of their different properties.

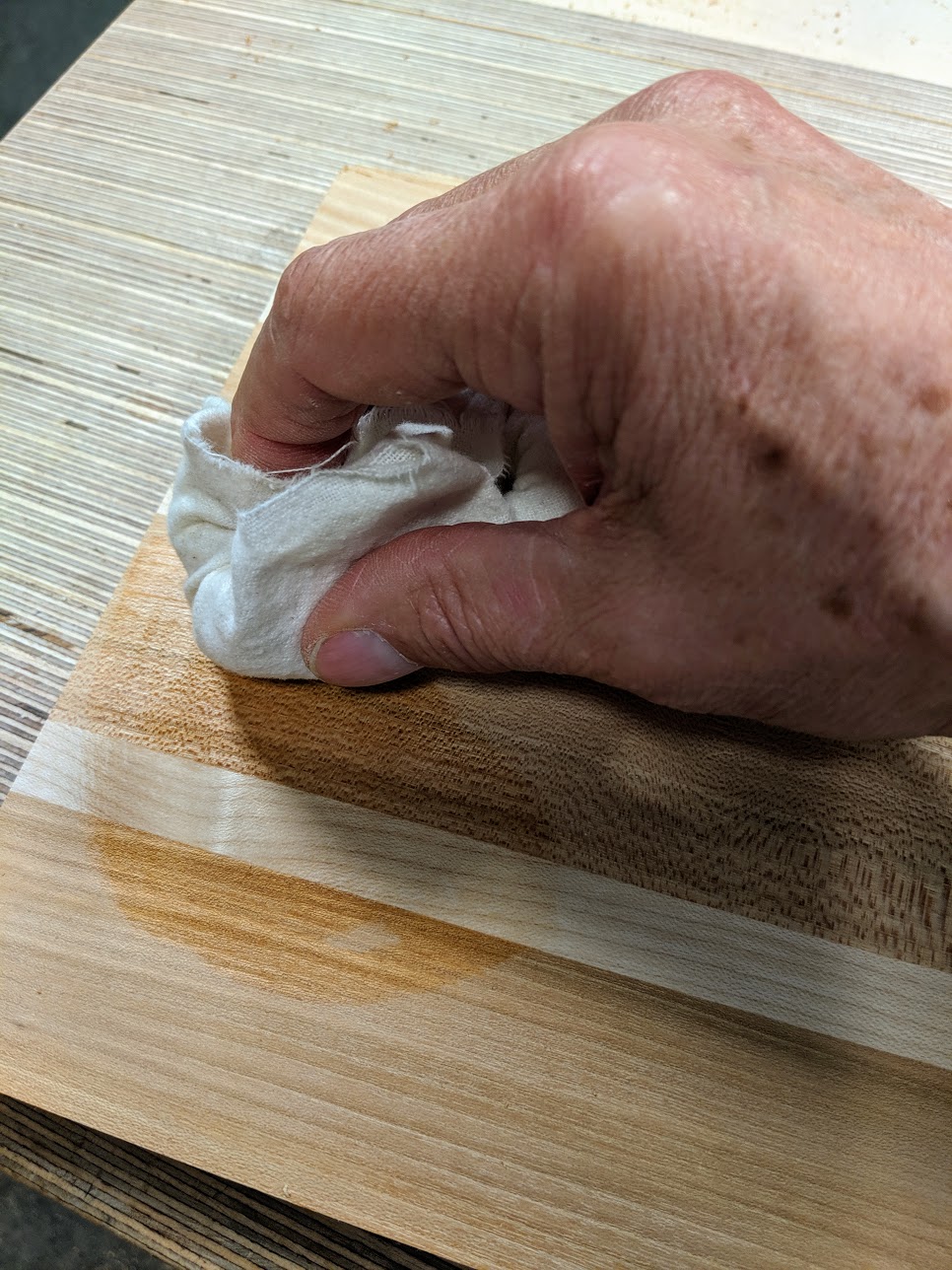

Oil finishes in general can comprise a wide range of substances some of which have zero oil of any kind at all in them. Some waterbased outdoor finishes are sold as oils yet the vehicle for distribution is water and mist of the residue after evaporation is actually plastic. Reading a bit between the lines, if it says water clean up it usually means it's not oil, at least of the kind we might be associating it with anyway. Boiled linseed oil (BLO) tung oil, Danish oil and so on are usually a combination of different oils with solvents designed to evaporate. They are often described as wipe on finishes which require only a clean soft cloth to apply the finish, though some can be brushed and sprayed on too.

Lacquers come in many forms with some being chemically based throughout and other being completely natural. Shellac is completely natural and comes from the excreted juices of the lac bug. Some lacquers come from tree roots and again are completely natural. Sprayed, rubbed or brushed, these are very versatile but can be tricky to apply in some contexts

On my new bookcase, made from east European redwood pine, I decided on my own concoction using outdoor finishes. Having sanded the finishes to 250 grit I was satisfied that the surface would receive and hold the light colour of the stain-coat (for want of a better name) and also result in only minimal raising of the grain. Indeed it was so minimal I didn't sand between coats and I got a very nice finish. It is always good to remember that the level of sanding will affect the colour. The coarser the surface the darker it will become. This is because of surface absorption. What I wanted was translucency, sufficient to still see the grain and knots through but enough to temper down the contrast. I also wanted to reduce the colour contrast that often occurs when pine ages.

I don't like the orange or redness that exposure to light ultimately results. I also like the way my choice evened out the overall appearance to produce a controlled outcome. I padded on one coat but I could have done two. The pad was the best method as this gave an ultra thin and even coat with zero texture. I applied two more coats of clear finish and no grain was raised at all. Very unusual. You might need to experiment as there are no guarantees, even within the same species. Bookcases take the least wear of all furniture pieces I think. Whereas the base coat of light colour is in fact a layer of coating, and the subsequent two coats of clear too, a third coat brushed on would give ultimate protection should you use this on other furniture like tables, chairs and so on.

Conclusion. If in doubt as to your skill and speed, a wipe on poly or Danish oil, boiled linseed oil and such are all ultra easy to apply. Shellac applied using a French polishing technique is not for the faint hearted and definitely requires a working knowledge of the medium, technique and so on. Start to learn on practice boards and see how you feel. Shellac is indeed brushable but your brushing technique will not be the same as applying emulsion paint to walls. It requires more method and good brushing technique as well as speed and accuracy, sensitivity and such. A sprayed shellac finish can come very close to a hand applied French polishing if you are experienced using an HVLP spray rig. I like to use this myself. I also spray on waterbourne clear coats using an HVLP sprayer and with care it will result in pleasantly smooth and acceptable finish.

At the end of the day I do like the look of a carefully applied brush finish where the hint of brush strokes kiss the surface with evenly parallel lines lengthways along the whole. It looks neat in the two senses of the word; cool and ordered!

Comments ()