The Shinto Raspy Thingy!

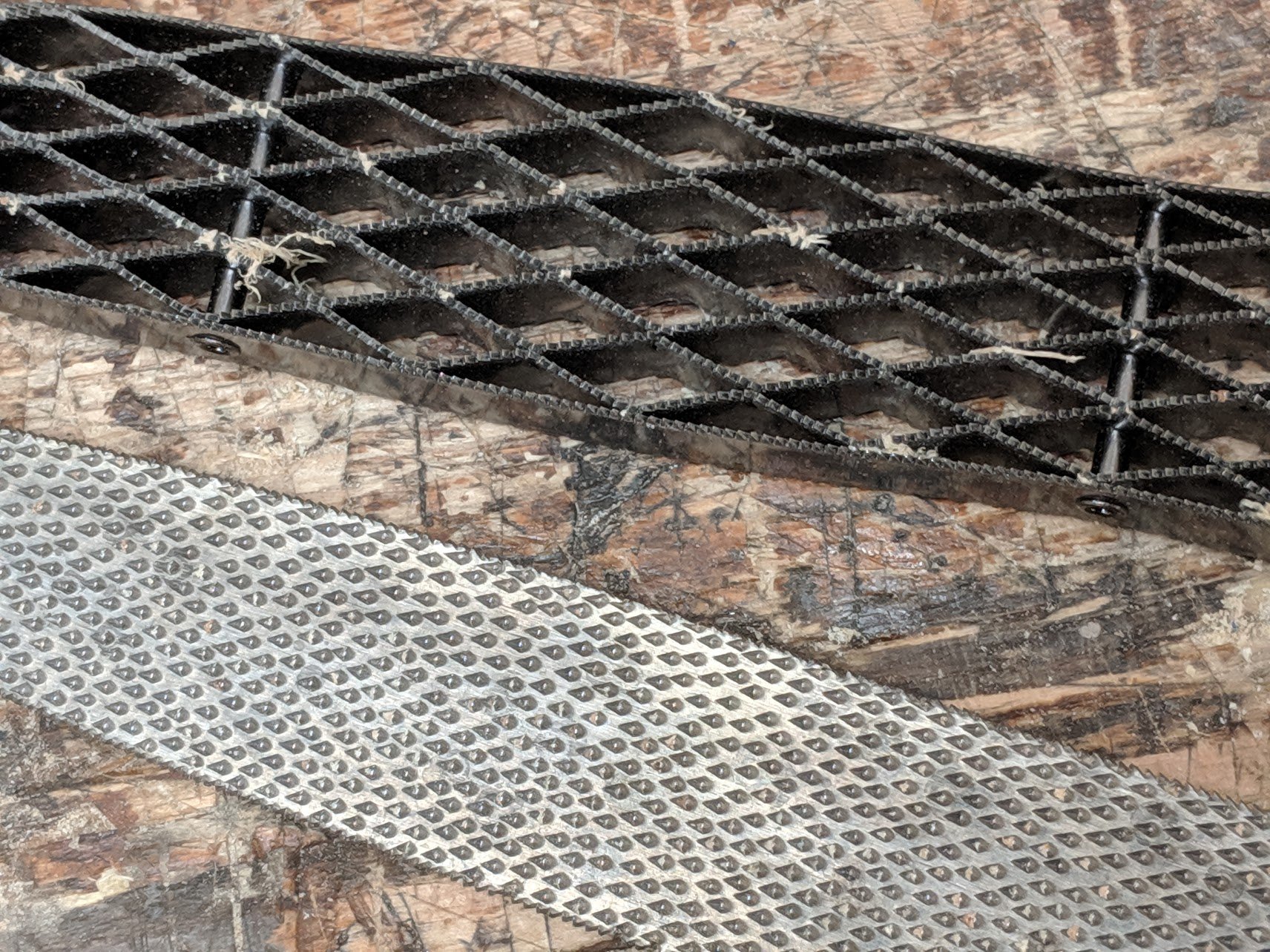

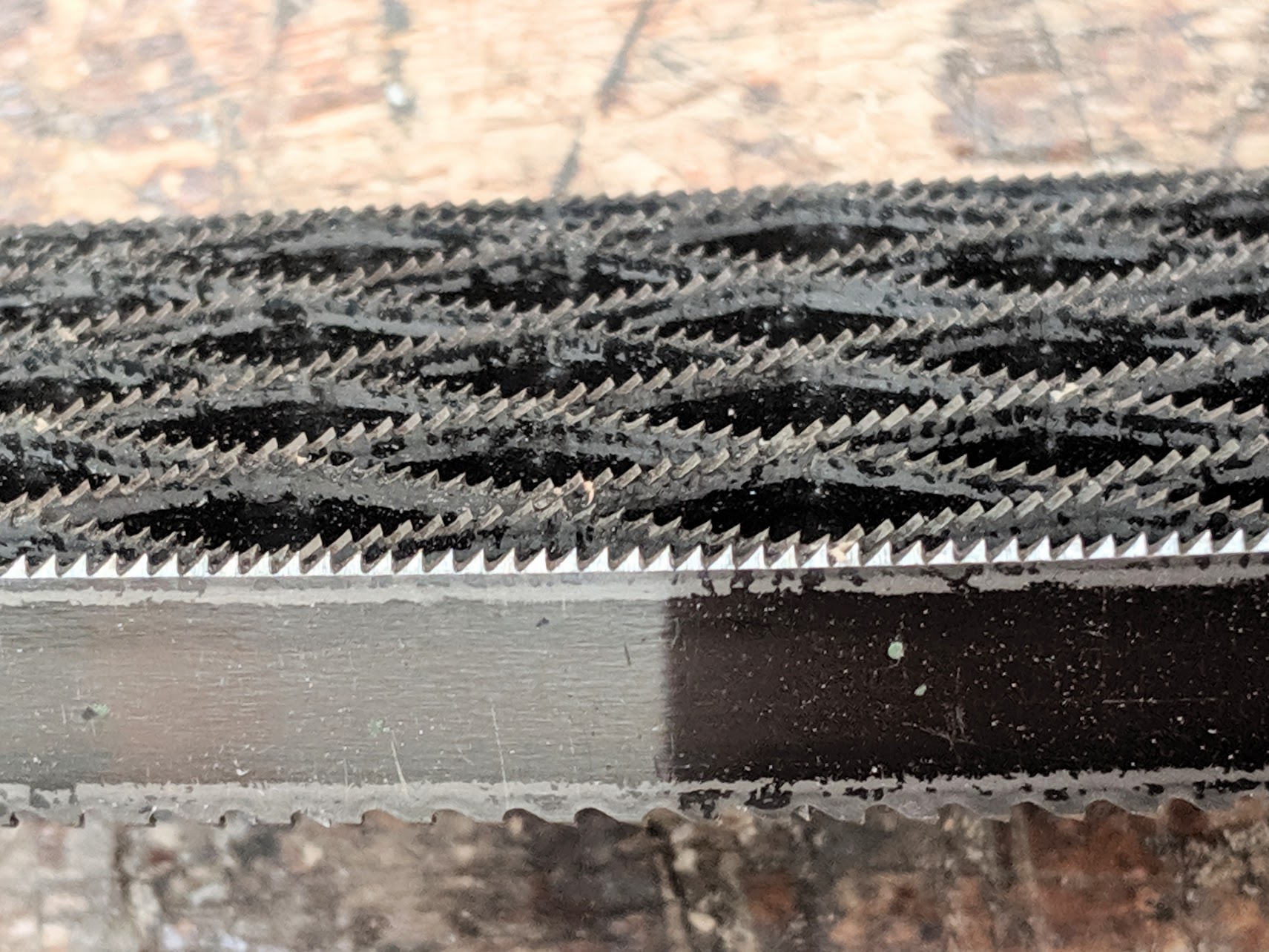

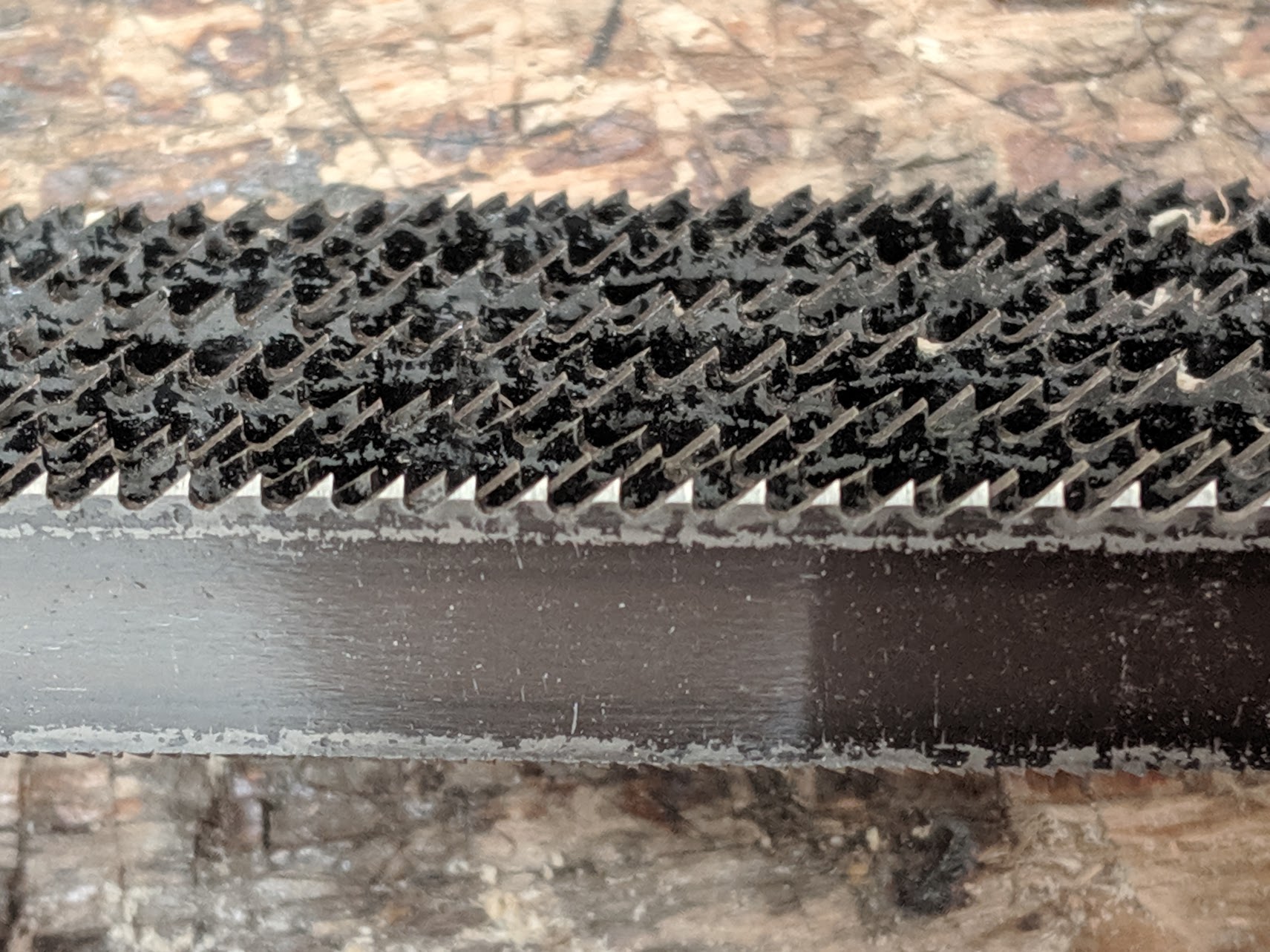

When is a rasp not a rasp? When it's a series of saw blades strategically locked together to form an aggressive cutting tool for shaping wood. Sounds like a rasp but it's not. Really it deserves its own title but then no one would know what it is because most of what we use is recognisable first by its name. As it is with many new designs in tools the maker somehow has to bridge the divide to say it does what this other tool does but it's not that its this. The maker or inventor must make a tool that identifies its function and purpose, otherwise the category and title might displace the tool and people are unlikely to discover it. Hence planer, filer, filer rasp, file, rasp file rasp and finally Shinto saw file rasp. The makers usually don't care too much about coming up with any other name than their brand. All they want is a saleable piece. The tool is one of those tools that relies only on assembly work and not a skilled artisan. There's nothing wrong in that, but comparing or naming a tool a rasp does not make it a rasp so nomenclature is everything. When we talk about a rasp in it's traditional sense we are talking about carbon steel that's been systematically and rhythmically stitched by eye and hand. Using his skill, the maker employs a hammer and a punch to cut and lift the surface of the steel in a series of arched cutting teeth according to his pattern of stitching. The pattern he establishes with each stitch becomes his signature and no two makers follow an identical pattern. With each stitched tooth forming a strategic presentation he optimises the cutting dynamic to what becomes the natural sweep or arc of the new user-owner. The smoothness in cut of a true rasp is the most amazing sensation with depth of cut and rhythm set by the user according to his working. But, as with all tools, not all tools are created equal. You can get good and bad rasps and a hundred levels between the two extremes. Once you have used hand stitched rasps by makers like Auriou or a Logier you are hooked (pun intended) and you will never go back to a cheap rasp. But cheap rasps work short term to see if you really need them for your type of working. Here is another truth. If you are shaping or making only one product such as a spoon, and you do not intend to make more and on a grand scale, buying a £110 rasp becomes prohibitive to most if not all woodworkers. I cannot imagine life without one.

The Shinto rasp justifies the title ugly. It's not a pretty thing like a well made and finely tuned rasp so let's not pretend. It does however have one critical characteristic that makes it stand out from the rest of the so called rasp family and that is it works and it works well. Running this tool alongside a finely made rasp you will reach for the finely tuned, hand made version over all others - hand stitched rasps stand out. But run it alongside a cheap rasp with machine stitching and the Shinto wins hands down. What I am saying is that often we are not comparing apples for apples.

The Shinto saw rasp is two cutting surfaces in one tool, coarse-cut one side and fine-cut the other. The coarse-cut face removes material as rapidly as a hand stitched cabinet rasp, almost, but I will not say that the surface is as good. It's not. I'm not sure if that really matters though because usually we do further refine coarse surfaces with more work, be that from another rasp, a scraper or sandpaper. In the case of the Shinto it's simply a question of flipping the rasp over to where you have the refining face of finer saw teeth that indeed produces a smooth finish. Follow on with a fine, 10" flat file and the surface smiles back at you. Now a cabinet maker's rasp is also two rasps in one too. This rasp has both a flat face to one side and around face on the opposite side. Something a Shinto cannot match.

So just what is the difference between the true rasp and the Shinto alternative? There is a rhythm that comes from using a hand stitched rasp that I did not get using the Shinto and my feeling was that you cannot get the same feel because the teeth are not hand stitched and are therefor perhaps too uniform. When teeth are perfectly uniform in any saw type there is a harmonic that sets up that is not so much a mere sound as such but more the 'wolf' you get with bowed instruments like violins and cellos. This 'wolf' robs the instrument of its pure note; not all the time but often when you least expect or want it. This harmonic I speak of in the rasp means that the tool motion you use is more counterproductive than effective and counters the effort you make in the same way any vibration can become counterproductive to energy. Think the shudder of bike brakes, an unwanted vibration in an engine that just keeps developing and developing, that kind of thing.

Conclusion: A definite positive buy. I found that a combination of two or three tools maximised my efficiency and reduced the wear and tear on my premium rasps. Using the coarse and fine on my Shinto did well to reduce the stock down close to size and then the follow up with my rasps gave me the refinement I wanted. The file smooths everything to a glass like finish. Very effective.

Whether you are making a canoe or kayak or a new surfboard, or refining the neck of a guitar or cello, this Shinto thingy will take you pretty much all the way. It's a serious tool.

Comments ()