Bits and Braces

I took another exploration into my Essential Woodworking Hand Tools book to look at the boring things of woodworking. I know, it should be belts and braces but I'm more talking about a safe practice than risk aversion. Brace and bit woodworking is a safe way to bore holes. It works at your speed and none of the energy becomes wasted. Of course there are disadvantages too. It takes both hands to hold the brace and so there is no free hand to hold the workpiece. Another thing is the swing of the brace as you rotate the handle to drive the bit into and through the wood, a good ten inches. Internal corners in tight spaces are hard to negotiate even if the brace mechanism does have a ratchet for forward, lock off or reverse actions. But it is all too easy just to reach for the drill-driver and that means the total abandonment of another tool that still has truly practical options for us to work wood with. All I am saying is for adult woodworkers with all their faculties there is a place for both. My worry is that 99% of woodworkers do not know that the brace and bit are well proven methods of work and that they were not necessarily replaced by something better or even more advanced. This is especially important where total control is essential and an overactive trigger finger might cost the work in progress. Drill-drivers wear out the component bit tips at a rapid rate: that's twist drills, pozis and so on, a hundred times faster than when relying just on your manpowered alternatives. One badly aligned drill-driver often ruins a pozi tip in a single spin off-piste - even in experienced hands.

I know what most people think about the brace and bit: outdated, old fashioned, why use one? Slow, inefficient, hard work and so on. Of course none of that's really true at all. The brace and bit is just less suited to modern-world workers in all categories of work where users have no longer been taught even how to sharpen a pencil let alone how to sharpen and maintain cutting edges to tools of this type; of course they are living worklife on the conveyor belt - mostly they have little option. But, think of it this way where in my world I grew up using the brace and bits most days. They needed sharpening every few days so I not only gained those skills but understood the essentiality of such actions. My work wasn't just to beat holes through stud walls but to create crisp clean holes with unflawed rims. Sharpness is always critical to fine work. Trades rarely comprise the fine work demanded by artisans in craft in the same way. They operate completely differently and that's in general is just the way it is. There were of course electric drills in my early days starting out. Mostly they had poor ergonomics and developed better ones over the ensuing decades. I doubt most electricians would get by with a brace and bit and a saws-all of some type these days but back in the day, before battery driven drill drivers, they worked better as the original cordless equipment, even for them. But mostly their needs are not the needs of the artisan. Mostly they are assemblers of component parts, same with plumbers, where bolt on wires and threaded connectors unite tubes to connect water or wires from source to supply, just not in a factory setting. In my work the brace and bit is irreplaceable for several reasons and not the least of which has been the safety in work they provide. Somehow they slow down my world to a workable rate within an acceptable pace best suited to my humanity. It's more the feed rate that matches my humanity that I always try to look for. I feel always in control. I'm always concerned about any possible damage to my workpiece and that mostly revolves around slippage, out-breakage, excessive energies resulting in damage and so on. I'm not mesmerised by speed and I hate the fact that a drill running a 3/16" bit through a 1" section of wood takes 2,000 revolutions when my hands turning a brace takes no more than 20. You pay for that. One way or another you pay for it. Of course boring holes for wires in 2x4 stud wall is of no consequence. A high speed auger bit does that well, but in other situations, in furniture making, I'm never really in a hurry.

A drill driver can and does go through drive bits in a heartbeat. That's why they sell them in packs of 20. A misaligned bit in the hardened pozi-drive screw knocks the corners off the bit in seconds, possibly unusable after the first use if badly really badly used or loosely held.

Anyway, I thought it was worth trying to see what the difference was between a drill driver at 1500 rpm and a swing brace at manpowered rate. It took 4.5 seconds to drill through 1" of oak with a 1/8" twist drill using a drill driver. It took 10 seconds and 19 revolutions with the brace using the same bit to do the same. So twice as long with the vintage brace and twist drill but but only one fifth the revolutions. Now for a 3/4" hole in pine using the brace and bit it took 8 seconds and 21 revolutions - very quick, I thought. With a powered 3/4" Forstner bit in a drill-driver it took 12 seconds for the same sized hole set on 1,500 rpm so took many more revolutions for the same sized hole and half as long. Anyway, I thought that the difference was not so great as I thought it might be. Of course we're not comparing apples for apples in that case but it was still interesting.

One thing I enjoy most about the conventional swing brace with its forward/reverse ratchetability and its auger bits, and it's a part that people seldom see or at least consider, is that with each hand turned revolution the bit achieves a controlled and measured depth of cut. This governance is in accord with the thread on the spiralled snail point. This snail pulls the bit ever deeper into the wood so we have the perfect controlled feed rate according to our human speed. On power-drill auger bits nothing of this synchrony takes place. You have 1,500 revolutions per minute with a threaded snail that does indeed pull but with not synchrony at all. Its the sledge hammer and nut scenario where the bit blasts through the wood uncontrollably ripping away in the hands of the macho-man. Such a wretched invasion of the workplace.

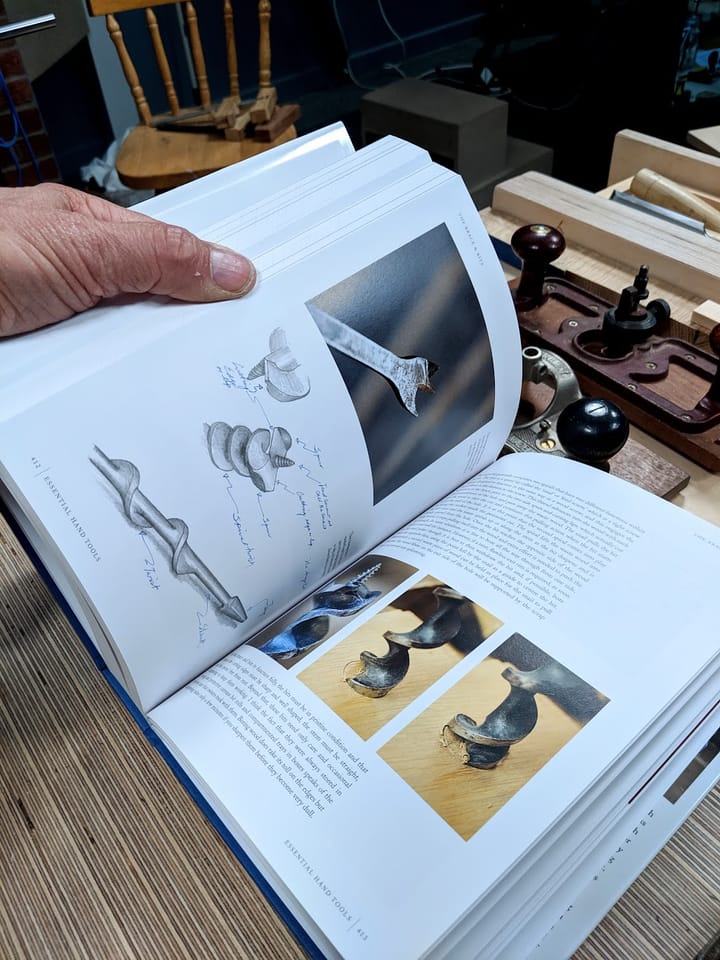

Let's look at my bits. The snail threads are uniformly even at 1/16" increments.

This reality governs the feed rate at 1/16" depth per one revolution. In this case , from the point hitting the wood, it takes 6 revolutions before the outer wings cut the rim of the hole.

I make one revolution and the whole rim of the hole develops the circular equivalent of a knifewall circumference. Lovely!

Once this rim-cut is done, subsequent revolutions engage the raker cutters between the outer spurs and the conical threaded point to bore the 3/4" hole. I took a total of 17 revolutions to pass through the stock that was over 3/4" by 1/16". This starts once I've cut the rim so the rest to excavate through to the other side. That means that each revolution deepens the cut at a specific cut rate, give or take, of 1/16" of an inch.

My depth of cut is therefore countable. A half inch depth starts when the rakers engage the wood surface and 8 full revolutions takes me to depth.

Comments ()