Try Something for Me

When I sharpen a plane I have a standard I work to. It's almost always surgical sharpness. Why? I'm not always sure. But I'm sure that most of us ultimately end up with a system and an order to sharpening. Ultimately we should all steer away from abrasive papers and silly names like the scary sharp method because craftsmen of old always sharpened their edge tools to surgical sharpness anyway. Or did they? What replaced the ordinary practicalities of everyday sharpening is a fascination for something that fascinated us away from the literal essentiality of working for a living. Not many craftsmen of old, and I include myself in this, had the luxury of gluing abrasive to sheets of plate glass or half an hour to sharpen and set a plane. It didn't happen. All the woodworkers I worked under took a dull plane to surgical sharpness in under a minute and were back to planing wood in under two. It was an ordinary and simple task and, yes, it was surgical sharpness without the fuss.

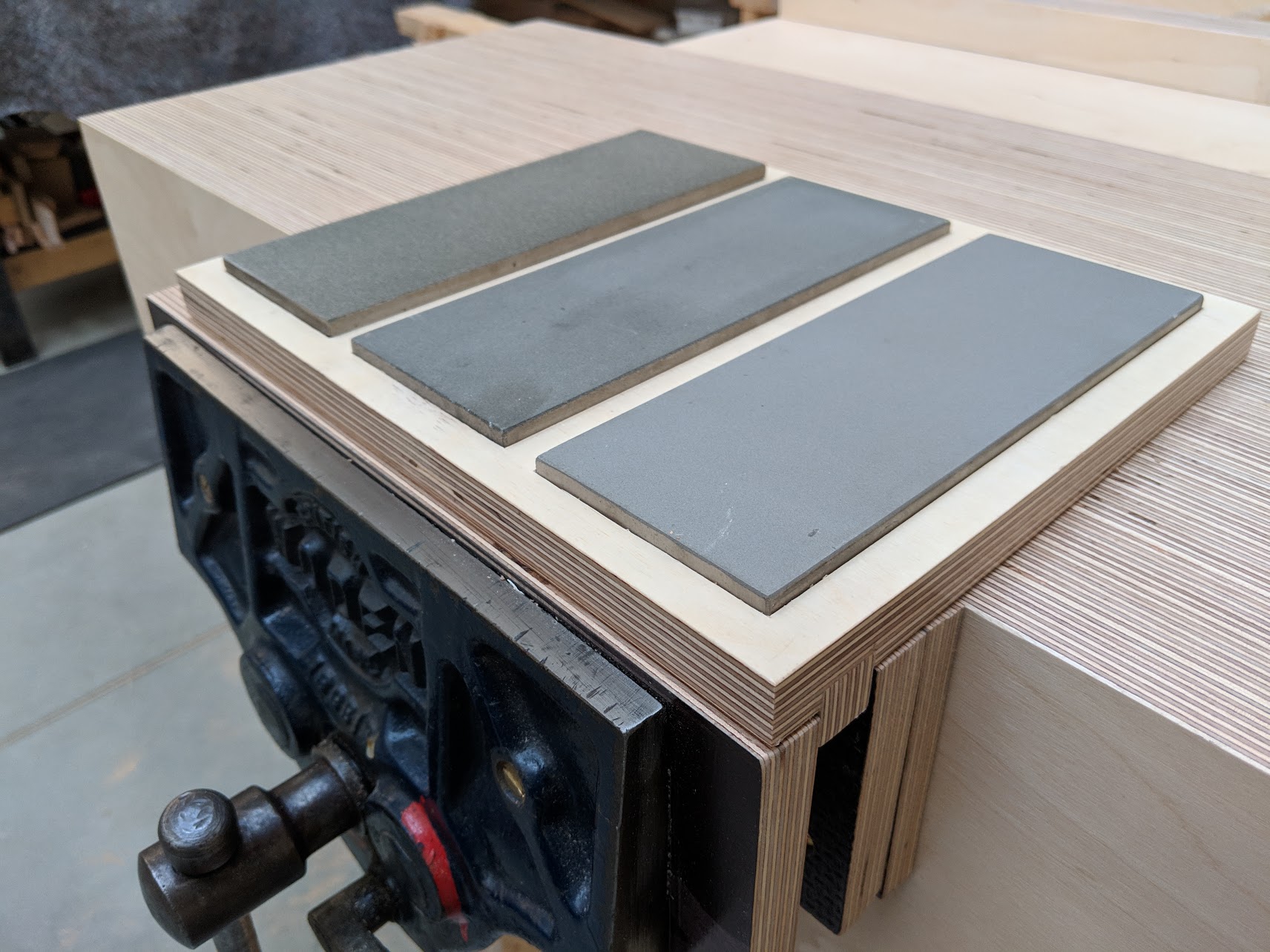

My teaching trains people to go through three stages on abrasive stones and then onto a finer grade using buffing compounds on a strop. It works. 250, 600 and 1,200 on stones, or thereabouts, not rigid, and then any steel buffing compound, around 10,000. This protocol gives you a surgically sharp edge. But the carpenters on job sites I have met usually grab the belt sander with 250 grit belts installed and flash the plane iron across the running belt at around 30 degrees. They are back in the planing mode in a few seconds and for the bottom of a door or the sticking stile of same it gets the job done and it's common practice. In my classes students in training take great pains to get the perfect result. Instead of my one-minute dull to surgical sharpness they often spend 30 minutes and they do so because they can. For me, sharpening is such an essentiality I would not work wood if I couldn't or wouldn't do it. I'm not a perfectionist and can't stand self claimed claims people have of being a perfectionist. As long as we work diligently to achieve good work it is good enough for me.

The job-site demands are generally different to bench work. Mostly the work needs to be finer. Not always though. I've known trim carpenters who work to high and tight tolerances in high end work. You see sharpness is key to ease of cut, accuracy and fineness. It is the most undervalued and least understood in the realms of craftsmanship. Most of the woodworkers I have known and taught have usually, not always, just mostly, shown reluctance to stopping and interrupting the work to go to the sharpening stones. In many cases they simply are intimidated by the process, but then too the reluctance is because they want to keep going as long as they can on the blade sharpness level they are at. The fact is sharpening has to be as much if not more of the planing, sawing, chiselling, spokeshaving, axing processes as the engaging of the tool cutting the wood itself. Though the task of sharpening is very different to the application of the tool to the material, it's important to slide from planing to sharpening and back to planing as seamlessly as possible each time you sharpen: And it is possible to get to a place where you don't even notice you're doing it!

There are levels of sharpness that I use. In my videos, if you see me sharpening up, you see me go through my recommended four levels in quick succession. Three stones and a strop charged with abrasive compound is fast and effective. In under a minute I have my plane or chisel sharpened. A saw takes me four to six minutes and I never put sharpening off no matter the rush - it just does not pay. But I don't always sharpen my edge tools to the 10,000 or more level. It depends on the work in hand. For instance, though a scrub plane might be engaged in scrubbing off large amounts to get down through the grain, sometimes I might not go to another level because it's unnecessary. Using the scrub to bevel corners in an instant, or planing a narrow edge where the edge is not needed to be united to another as i gluing up. At my bench you will generally only three favoured planes I reach for in a given day. I have the scrub plane, the jack #5 and the smoother #4. Tucked away but still close to hand I have a #5 1/2 and a #4 1/2. Behind me I have a couple of extras of each and then a couple of Veritas bevel-ups.

So here I would like to ask you to simply try something out for me, just to see what you feel, so you understand. Sharpen your smoothing plane to 250 or thereabouts. Use it to plane say oak and pine. Take a few swipes, set to deep and shallow cuts. Run your fingertips over the surfaces to see how the surfaces feel to you. Register your feelings in your memory bank. then take the iron out and take it to the 600 level and try again. Now to the 1,200 level. Doing this is sensory. You will register feeling and learn how such feeling works as you work your wood. From this you can evaluate exactly what level of sharpness you need for the tools you need to sharpen. I often find that 250-grit sharpening seems to engage the wood or some kinds of wood better than going up to the 10,000.

Comments ()