Milling Oak...

...For My Garden Bench Parts

So it's oak. It's 5" thick and you need 3 1/2". There is no doubt that the bandsaw makes shorter work of ripping it to size but there is still plenty of labour surface planing and squaring up adjacent faces. My hands slowly and tentatively slide over the surfaces of beams.

I feel pin pricks from the surface in my fingertips, especially the forefinger and ring finger. I can tell the grain direction from this one act. In one direction and smoothness in the other pin pricks. I sense what's not seen to determine where the grain rises against the tips and I stroke the surface with the plane according to my senses. I'm always reading wood beyond sight. My ears tell me what cannot be seen. Those subcutaneous senses sense too what's inside the fibres and defy sight. It's subtle. I use to take such things for granted in the same way the men I worked with did when I was a boy. I'd watch them flip boards and beams from face to face and edge to edge, this way, that way. All the time rubbing their hands over the length and breadth of it. This dark art of board and beam flip stayed with me.

At 15 I'd start doing it too. It started to become a habit. They would spend minutes searching the surface with their eyes and tracing the patterns left from bandsaw teeth and the kerf from circular saw cuts, as if listening with the ears of their fingertips. Everything revolved around the tips of their fingers and then one day I sensed what they sensed. There it was. Vibration! Echo of flexing fibres above hollows and voids. For months I tried this and the minutes of trying led to gain. The insights they had and knew meant nothing at first but with perseverance I gained insight to the inner fibres of wood. I could feel for density through weight. Compression from between my fingers and thumbs. Though at first I had no register recorded to make comparisons to.

They, George, at first anyway, chuckled. "What do you think you're doing?" I didn't answer. I didn't have an answer back then. I was studying, searching, striving. I had to know what it was. I went to pick up wood this week, twice actually, and the man watched me and then asked me the same question George had fifty plus years ago. What is it you're looking for. He couldn't see what I was doing even though he'd worked with wood sales for years. "Just listening. " I said. "What for?" "Oh, this and that." I couldn't really say 'a sort of a voice.' I could hear the voids and the parted ray cells, open pores, denseness and such. I don't know. It's what I can't really see so much as what I might feel and hear. I gave more explanation than I thought to be any good. I thought he understood though.

When I got back at 8pm I wanted to slice of an inch in the width to measure the moisture level. It varied between 17-20%. A garden bench lives outdoors all the time so that works for me. It will check when the sun hits it for a few days, I know that. Unless I coat it with something. But then if I coat it I have maintenance every three years and even then there are no guarantees. I had some oak beams in but they were only a year since cutting and stickering. The MC was 28%. In a years time they too will be down to around 17%. I'll save them for a couple of years. You can always use heavy stock.

My first pass into the bandsaw was nice. A new blade always does well. get the tension right and it will keep its track. I decided on a six tooth per inch blade and it sliced without effort. One blade did all of my garden bench stock and it is still sharp so it will keep going for a while. Generally I don't discard my blades because they will usually cut thinner stock up to an inch for much longer. Usually I will use them for freehand work until they give up the ghost. It is important to see bandsaw blades as consumables. I meet too many woodworkers when expect a year out of a blade. Though it depends on the wood, wood type, thicknesses and such, blades should last for a few hours of cutting. For around £13 I have my wood resawn from heavy stock to planeable sizes. Enough to skim off but not more than 1/32". I use my bandsaw differently than most. We are planning a video series to show exactly what I do.

My steps give me minimal waste. My sensing helps me to make good choices. Avoiding subsurface voids as much as I can leads to make the most judicious cuts. It doesn't always work, but if it does nothing more than slow you down and think then that's enough anyway. Listening to that still quiet voice inside can only be a good thing, right? And if you're right you've gained, if your wrong you will have tried and probably lost less at least. Prior to this I had bought some oak boards to cut down to narrower widths of 5", 3 1/2" and 2 1/2". The board are 1 1/8" to 1 1/4" thick so with judicious cutting and planing I can just about get what I want/need. On some of it I can go thinner if I need to. Up to an eighth or so would be fine. the beams I bought must make 3" by 3 1/2" stock so bags of extra to cut from and enough to let dry for other products later.

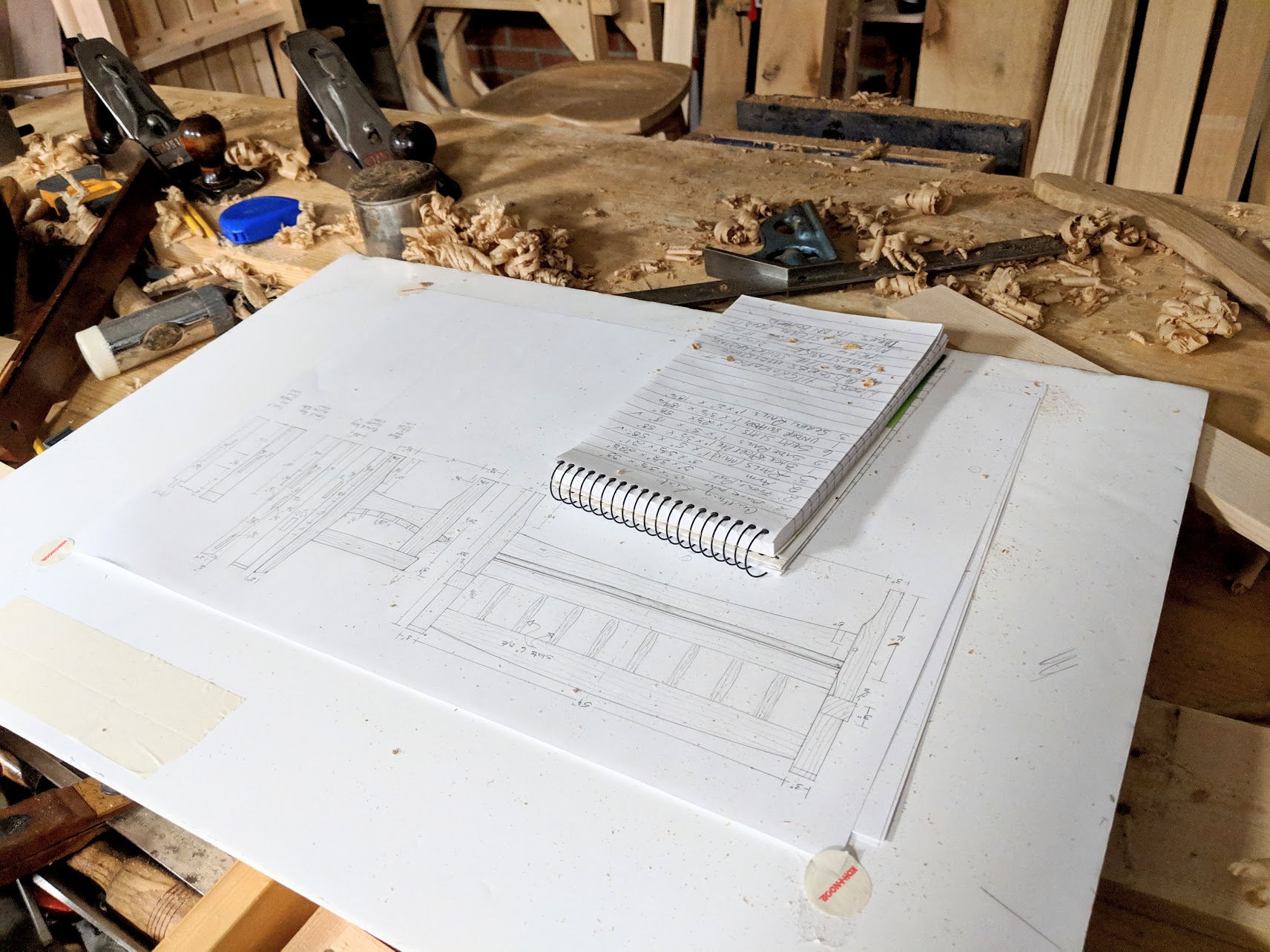

My steps are pretty standard. Mostly this is observation work. My cutting list and drawing is close to hand at this point. One thing I hd noticed is that much of recent stock had never had painted ends. This means that stock kiln dried had higher levels of checking in the open ends of the boards. This results from the ends drying out much more quickly than the centre body of wood. `the end grain releases its moisture much more readily than surface grain does. Usually the mill paints the ends to slow the release in the ends down. It generally works well even though some splitting can still take place. Split, check and shake all mean the same thing. The drying process finds the weakest point and shrinkage results in an inevitable split. Only when the moisture levels drop below around 10% does the wood stabilise and the risk of splitting lessen. Even if you get the MC down to zero, were that possible, no wood can remain at that level in a natural environment unless of course there is no atmospheric moisture. People generate moisture in the environment they live and work in. Homes have high MC. Showering, cooking, breathing and living generates humidity. It's a given. Yes you can lower MC with heat and ventilation but it's not healthy to remove all moisture even if that were possible. Whereas my legs are at 17-19%, my thinner stock is a perfect 5-7%.

Tonight, by 5.30, my oak was all milled and hand planed on every face. 30 pieces of so and then a few spare just in case. I feel happily tired. It is still quite a work out even with the bandsaw doing the donkey work of rip-cutting, but I am not sure I want to change a thing!

Comments ()