Garden Bench Finishes

Finishes come in many different forms. The confusion is great and opinions based only on opinion and little more serve to make things worse. I'll try not add only opinion but tell from my personal experiences. It might work.

Oils intended to soak into surface fibres are supposed to, as they seem always to say somewhere on the can, "penetrate deep into the wood to give maximum protection from harmful sunlight, harsh rains and wintry weather" or worse still, "Nourishes the wood." Most usually don't. Often they do little more than harden up on the surface. Many if not most finishes create layers of thin film to build up coats into a thicker overlaid surface treatment intended to work as a physical barrier that's not unlike a physical plastic sheet basically sucking itself to the wood's surface first and then each subsequent coat sucking itself to the previous coats. Of course all of this relies on some adhesion. Sand it too smooth and the finish often peels off more readily. I'm thinking polyurethane and varnish here, whether they have spar, yacht or any other prefix to the name. One completely water-based finish describes itself as an outdoor furniture oil when no oil as such is used in the manufacturing of the product. At least that's not oil as we might know it where there is an oily substance resembling a barrier to water. Outdoor wood finishes then can indeed have such diversely different chemistry as far as ingredients go it is hard to decipher exactly what the product really is. It would be impossible to take all of the different types and say these provide us with a one size fits all finish. Often they cannot be described even as a particular finish type hence the common use of terms like 'oil', 'varnish', 'finishing system' and so on.

Danish oil, for instance, can be made by six different makers, six different ways and each with entirely different ingredients and they can all be called , well, Danish oil. Whereas on Wiki it might give you a definitive answer, it is also false to declare it as Danish oil because of its formulation. I say all of that to say there is no defined formulation to its composition. As a rough guide Danish oil is very generally a combination of tung oil and varnish with other solvents to aid curing through evaporation. Tung oil would be the major ingredient with varnish usually making up about one third. The fact that there is no such thing as Danish oil as an actual oil, that is it is not an oil produced in Denmark nor is it necessarily grown or sourced there. It is the same way Canola oil is not actually an oil from a canola plant or oil taken from the ground in Canola. Canola is simply a branded oil developed from rapeseed by Canadian developers and the the name partly tells the story. "Can" shortened from Canada, and "ola" from other vegetable oils makes up the made-up name.

Oils, so called, may have little to do with oil as such and will more likely be a mix of ingredients designed mostly to evaporate. As we all know oil, when spilled, remains oily. In general we are looking to apply a finish we can touch and recoat in a few hours and at least sit on by the following day. To achieve that, most finishes must have solvents that make them fluid enough to apply thinly and evenly and yet leave the product on the piece by gradual evaporation of those solvents that thin it for applying. The most efficient evaporatives are what are referred to as volatile organic compounds (VOCs). In normal room temperatures these compounds have a high vapour pressure which leaves the finish to cure to a touch-dry level rapidly. Because VOCs are harmful to the atmosphere we saw the introduction of finishes with low VOCs come to the market, mainly as water-based alternatives. Many oil finishes are a combination of chemicals and naturally occurring oils extracted for the purpose of creating wood finishes. Linseed oil, tung oil and many others have been popular through the centuries. Using some oils on their own and without the introduction of solvents will leave a natural barrier on furniture as a so-called finish. Often these natural products are not so durable and so manufacturers add other ingredients to skin the surface with greater durability. That is why some surfaces, though coated with finishes, like say Danish oil, actually feel like they have a plastic coat rather than a more natural oil feel.

Our minds tell us that an oil finish will be the better for outdoors because, well, "oil and water don't mix." Adding a little polyurethane increases the resistance to moisture absorption and especially is this so when the first coats have been applied. It's what happens over the coming months that changes the game. In seeing how makers sell their products, and indeed YouTubers demonstrating their application methods, you can be forgiven for thinking the oil is indeed actually "penetrating deep, deep into the wood's fibres". You can also be forgiven for believing you are "nourishing the wood". None of this is true at all. Wood does have some degree of absorbency but different woods have different densities and it is this that says how deep any oil finish might penetrate. Mostly you will be applying a surface treatment of zero nourishing value with extremely little surface penetration.

Many things affect the actual finish type applied, whether it is the actual wood type itself, the condition of the wood, maybe the prevailing weather for the area i.e. saltwater, salty sea air, pollution, wet and humid atmosphere and so much more. On the can the manufacturers usually start their application instructions with something like, "Ensure that the wood is dry and free from grease, oil, dust and wet'. For most people this is more an impossibility because most people don't realise that some woods are naturally oily or greasy and rarely do they have the ability to probe the wood deeply enough to know just how wet the inside of the wood actually is. Wood is rarely consistently dry to the same level throughout each stick and stem of wood in a project.

Buy wood that has been stacked outside for even a few days and the wood will be wet inside. When wood is still fairly wet with say 18% moisture in the wood, exposure to heat and sunlight will cause the wood itself to express the moisture to the surface through the porosity of the wood with its millions of cells.

Before this happens, and we've applied our three coats of finish, any increase in temperature will adversely affect the finish to the point that it effectively parts off the skin of finish applied, often resulting in a separated coat. Also, generally, what any manufacturer gives out as a general guide for the user is very, very general and to the nearest of possibilities relating to that product. In my experience it has yet to become an exact science because conditions are so diverse surrounding the place of application, the skill levels of the user, the wood properties and condition, type etc. Applying some finishes to say oily woods or extremely hard and dense grained woods is often a sheer waste of time. The truth is you can only generally believe what it says on the can because it's the diversity of conditions that dictates longevity of any applied finish. We are talking about outdoor conditions in which we plan to leave outside our outdoor furniture pieces. In most regions of the world they are either completely unpredictable, utterly extreme or both. As I have said, some woods, because of their containing natural oils or high levels of density have their own inbuilt resistance to any longterm reception of finishes.

Some finishes arrive in the can as a thick gel with instructions to either stir or not stir depending on the type of finish. Stimulation to some finishes by brush or roller causes what starts out as a gel to become more viscous and flowing. These thixotropic finishes are different to other varnishes or other oil-based or oily finishes. As I said, many oil finishes are a mixture of oils, resins and evaporative solvents. Older products like Spar varnish and others used to protect long term literally result in a series of coats that cover the surface as layers of skin. The solvents used to liquify the material for application evaporate over time and leave a hard and resilient skin. On a mast or spar, rounded in profile, this works really well as does the simple outer of a curved surface like a boat. Often there is no beginning and no end as the coat connects with a full revolution of wrap-around wet-edge-to-wet-edge painting whether brushed on or sprayed. Because it is seamless and there are no internal or external corners the finish will always last well. Here I am talking paddles, oars, spars, masts and other rounded parts and such. It is when you do get to a complexity of interconnecting parts as abutments that you face the reality that the skin applied stretches and or shrinks to cracking or separating points. The 'pull' and 'stretch', caused by the extremes of cold and heat, result in surface cracks and separation somewhere be that near the changes in direction or over a wide expanse where the surface skin fails to expand at the same rate or speed as the wood. Moisture enters any fissure, freezes or heats up and before too long the skin has parted from the body of wood or previous coats. The main reason we remove the corners by planing or sanding to a slight radius is not so much for personal comfort but more so to increase the likelihood of creating a continuous surface that 'bends' around the corners to realise the desired continuous skin. Many of the older finishes and indeed many used today are solvent based and this generally means they have high VOCs. We have seen a public shift from various finishes with high VOCs to waterborne finishes that are easy to apply and clean up and are considered less harmful to the environment even though that may be questionable as we are now finding out with plastics. Many varnishes are made from a wide range of different ingredients. Some innocuous and some harmful.

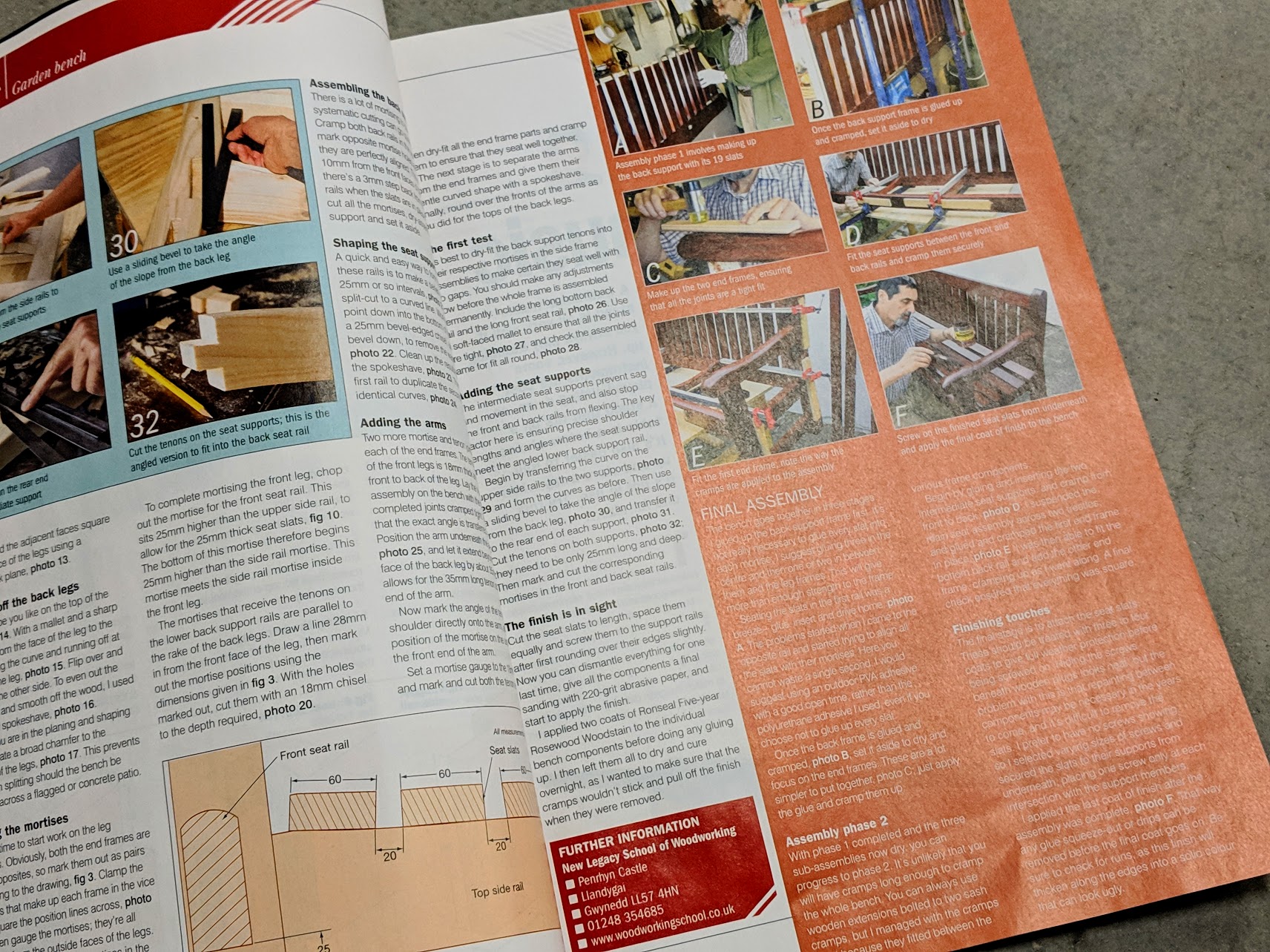

Many oils are supposedly safe. The question, as with many things, is do we really actually know? Stir it and it thins to a liquid. Usually they come as a surface skin brushed, sprayed or ragged over the wood to leave layered coats as a final protective finish. Though often espoused as long lasting and protective, most varnishes cannot literally seal off the inner wood from the harmful elements of weather over the long term and certainly there is no such thing as an indefinite finish. In reality the protective seal usually breaks down with the sun and weather and it almost always breaks down at any and all intersecting junctures around joints and the corners of the wood. To reseal is to allow the fluid to flow down or into the corners again and the reseal elongates the length of protection for another season. That's at least the theory. My most successful record for a finish to date has been on an outdoor garden bench I made in 2010 for an article I wrote for a UK woodworking magazine in 2011. I used a waterbased product made by Ronseal called Ronseal 'quick-drying' Woodstain. Anyway, I'm about to recoat with the same varnish. Whereas I think it is true that we generally want to protect and preserve the inside wood for as long as possible to get maximum use for whatever outdoor piece we have made, I think it is equally true that we really like a smoother surface to sit on, rest on and keep clean that a varnish of some kind gives us.

Leaving wood with no finish on will result in a rough surface even when we wet the wood to raise the grain and then sand. Wood left with no finish containing inhibiting properties for ultra violet rays will ultimately lose all its natural colour. Makers of unfinished products use this as a marketing tool to say the wood will take on a natural silver grey colour over time. In reality it is not taking on any colour at all as it is an achromatic colour literally meaning it is a 'colour without colour'. It falls somewhere in between black, a non colour, and white, also a non colour.

I am not yet fully settled on what to use on my new garden bench. The pine pretty much has to be coated with some protective coat because of its lack of durability. Remember some woods, teak, and several others are almost completely rot resistant (which gives it a life expectancy in excess of 25 years intreated), woods like sapele and oak fall somewhere in the mid range so generally lasting around 15-25 depending on whether you take it indoors for some of the worst weather years or keep it covered periodically. Pine, without any protection and left out in all weathers will perhaps last only last 4-6 years. With finish you can expect longer life, I believe, but it will as said above depend on your determination to finish well and be prepared to recoat every five or so. I cannot guarantee this for all of the reasons given. Coating with oil will give you a couple of years of colour before the breakdown begins. It's a matter of personal choice.

Varnishes can now be resin-based, chemical based or water-based. Oils are available but the reality is they are often unpredictably evaluated. You must remember that the longevity of finishes can be dependent on the wood type yet the wood type is rarely mentioned by paint and finish manufacturers. Some woods have a very short lifespan if left to the two most damaging elements. Wet wood succumbs to fungal attack, pure wet rot and a range of other degrading affects. Sealing wood can seal water out AND seal water in at the same time. Once a piece has been left outside for ten years the wood may well be saturated inside in areas you may not be able to find. Applying a coat of varnish without taking the piece inside for a few weeks or even months may well result in sealing water inside the fibre of the wood you are trying to protect. When the sun shines the wood shrinks or expands depending on the amount of moisture in the fibres. In a new build it is best to allow the wood to acclimate to its surroundings but not too much. A 10-11% moisture content will work well. Applying three coats of a reputable wood finish will work well before exposing it to the permanent outdoors if indeed you do want a finish. With waterborne finishes. I prefer to coat some parts before assembly because of awkward access. It is up to you whether you glue or use draw-bore pegs to keep the parts permanently together. I am of the view that glue, any glue, waterproof glue included, will hold in water, disallowing the release of water from the wood in most cases On my two benches I am going to rely on the draw-bore pins alone and no glue. I plan to finish the pine one with the Ronseal outdoor finish again. the oak one I will leave for a year and see how I feel then.

My concluding thought is this. We all want to believe in this or that finish as the best one or indeed our own concoctions that may well be as good or bad as a leading manufacturer. In the end it is only by trial that we discover what is best for own environment.

Comments ()