George Goes the Extra Mile

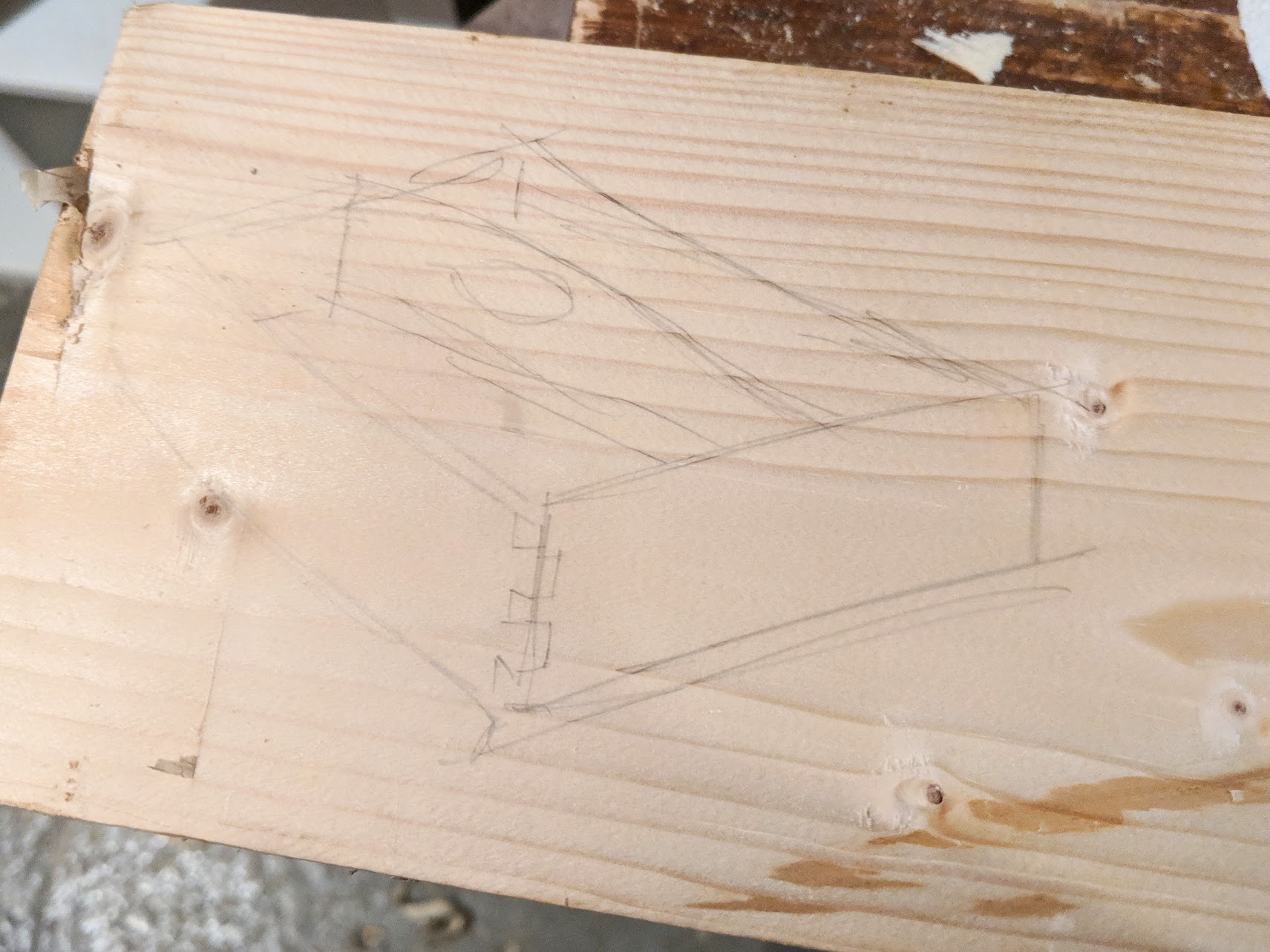

George was watching me from his side of the bench. It wasn't so much that I felt it but more noticed he'd stopped moving. "What's that?" he asked.

"It's a cutlery tray for silverware." I answered.

"What's it for?" he enquired.

"It's for Mrs B, the cook at the outdoor pursuits centre where I go at weekends to help out. A present, actually" I said.

"Looks like a spider criss crossed the board. Bolder. Bolder! Stronger lines. Prove your intent. It's a sketch not a technical drawing! Look like you believe in it, Paul. Believe in yourself!"

Drawing things out on wood as a note has become common all through my life. The plane works as an eraser for a clean sheet and it's cheaper and more eco friendly than paper. That wasn't the reasoning though. Mostly it was convenience.

George looked more closely and saw that it was more technical drawing than sketching. He asked about sizing, thicknesses and such. Digging in the scraps he found two thin pieces 3/8" by 2 1/2". We'd never done dovetailing together before and there we were in work time laying out the cut lines, shoulder lines and angles. I was in the best place I could be. The mystery of school dovetailing was about to be dissolved before my eyes with the myths and mysteries busted. This one lesson would be the way I would do them forever. I added the knifewall technique. I hated the marking gauge bruising and refused to do it after my lesson.

The first thing George did was make me clean up all the faces with a #4 smoother, one he had loaned me at the start of my apprenticeship. We used a tenon saw for cross cutting and a shooting board for squaring the ends. These were fundamental methods that would always remain with me as foundational. I felt clumsy and George said, "Own your plane!. Grip more loosely. Smooth out your action. Press confidently only when you have confidence to work with."

George took my wood pieces and checked them for square all around. He checked them for parallel when one end was square from one edge and out of square from the opposite edge. It was out. He explained about accuracy being multi-dimensional. That plane geometry can be cross referenced in the same way accounts can by three column accountancy. I got it!

George tore down the shop on his massively long legs with my note board in hand. Five minutes passed and he placed the thin sections on the benchtop. "Tonight we begin!" he said. "When we're done here."

George and I walked up to the chippy at five thirty. Fish and chips in those days came wrapped in newspaper. Until the EEC, subsequently the EU, stopped it. We walked down the cobbled streets eating our supper. It was cold but the chips were piping hot. All the men had gone by the time we got back. George reached up the top of the door lintel for the padlock key and we went in. Lights flickered over the benches and we started making dovetails. We did a corner each. It was only after half an hour that I realised. George and I had become friends. That he was truly enjoying this as much as I was. We chatted back and forth; bantering was very much a part of our being with one another. George never swore, ever. When things went wrong he was self controlled. He was fine example to me. All the other men swore all the time. This evening would capture the embryonic moment when conception would eventually birth many things for me. It was the birth of understanding accuracy of the absolute essentiality of sharpness. It was where I learned to plan, master the tools, to release true power of woodworking. This was the juncture skill and the important thing for me was that I absolutely knew it. This was where a man took a boy and freely gave him the true altruism of pure knowledge. George was teaching me to give freely anything that I might learn. He was ensuring the skills I might ultimately master would be passed on into the future. The skills and knowledge were of course for me, that goes without saying, but it was also for those I might come across in the future generations. It was all because of a simple cutlery tray.

A man wrote a sign for his shop wall. It said, It's not what the boy does to the wood. It's what the wood does to the boy!" His name was Sam Bush. Sam was a woodworking teacher in the USA who ended up with multiple sclerosis and the man that gave him this saying was a man from Eastern Europe before the wall came down. I'm giving it to you with the caveat, "It's not what the child does to the wood but what the wood does to the child!"

Enjoyed it!

Comments ()