Purpose of a Stopped Housing Dado?

There are good but perhaps somewhat hidden reasons that we use stepped housing dadoes that may or may not be obvious, especially not to a new woodworker. Actually, many seasoned woodworkers are more likely not to know than know. There are three types used mostly and then variations on the theme that are scarcely used. It's actually perhaps quite less usual to use the common or through dadoes in our present climate of hand work than in previous centuries when so much woodwork was created for factory and workshops used between the 17-20th centuries. Rarely would a through housing dado be used in the manufacture of fine furniture pieces. What replaced wood in those previous centuries for use throughout the last century and on into this one was sheet metal, plastic and composite sheet goods made from a wide range of mixed materials. That being so, we saw the gradual demise of the through housing dado because we saw a massive reduction in wooden cabinetry where it might be used the most. Beyond that we saw the steady development of a wide range of metal fastenings that were originally designed for industrial manufacturing and have now spilled over into the domestic suppliers. Is the dado extinct then? No, at least not in the realm of the hand tool enthusiast. Housing dadoes are practical and made with ease by hand methods so let's look at them and see how and why they exist for us.

The through housing dado was more the utilitarian form of housing dado joint; used as it was to build masses of equipment and furnishings such as shelves in kitchens and sculleries, below-stairs rooms where staff catered to the rich were filled with functional equipment ranging from butter churns to clothing presses and then drawer backs, firewood boxes, carriers and so much more. The working environs where pretty was unimportant and function key to speed, simple joints like the common through housing dado was a must in the making.

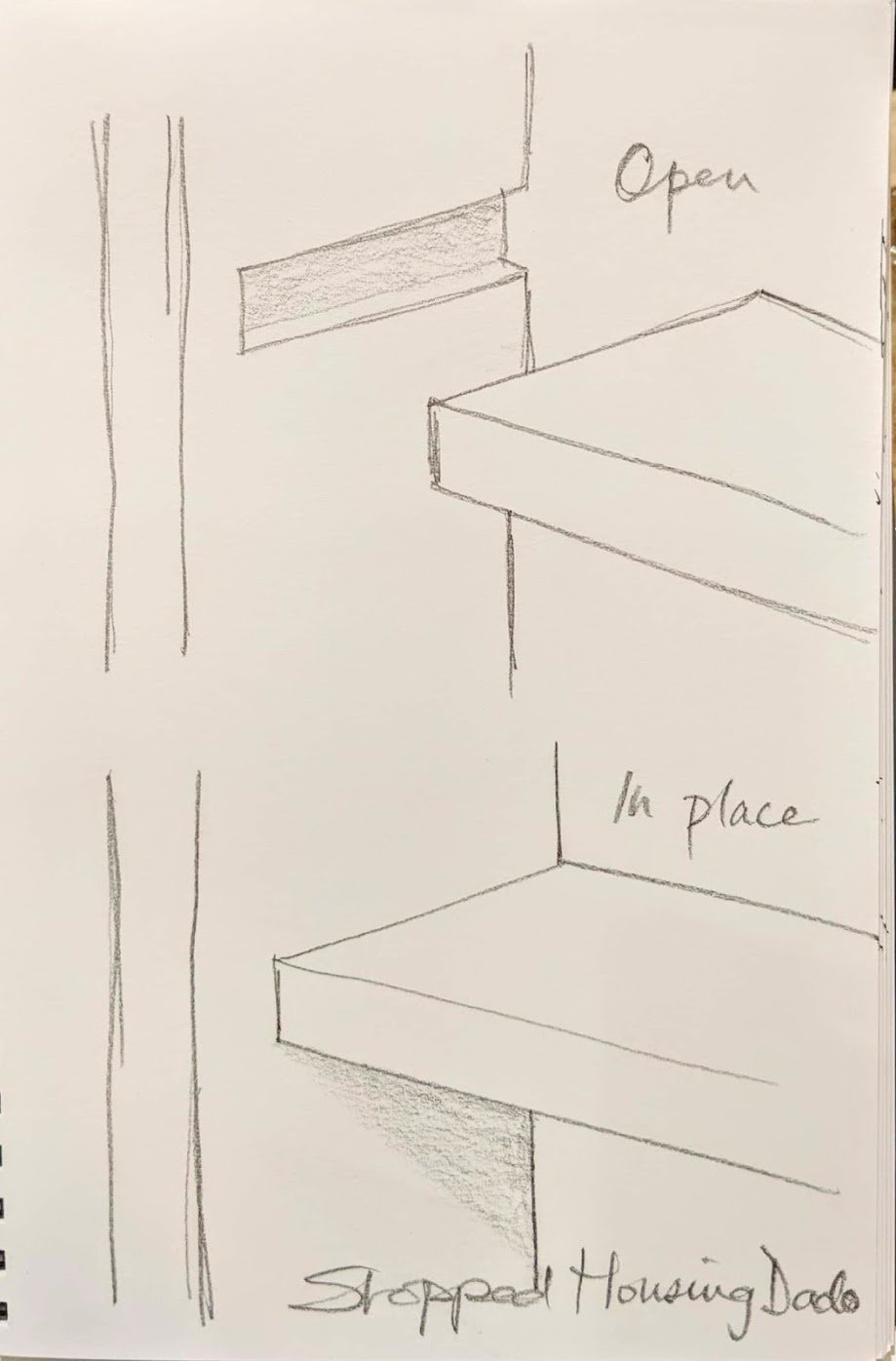

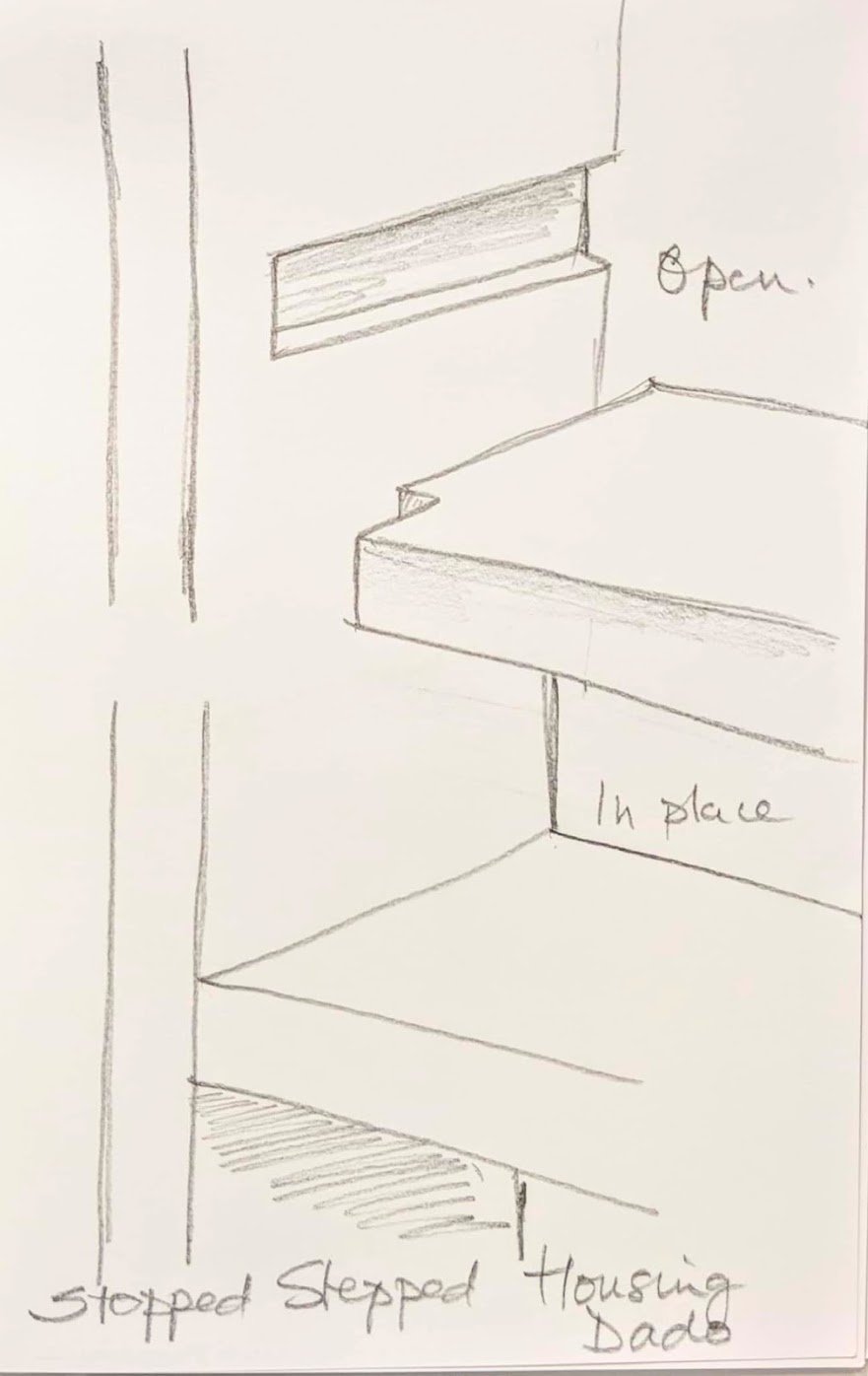

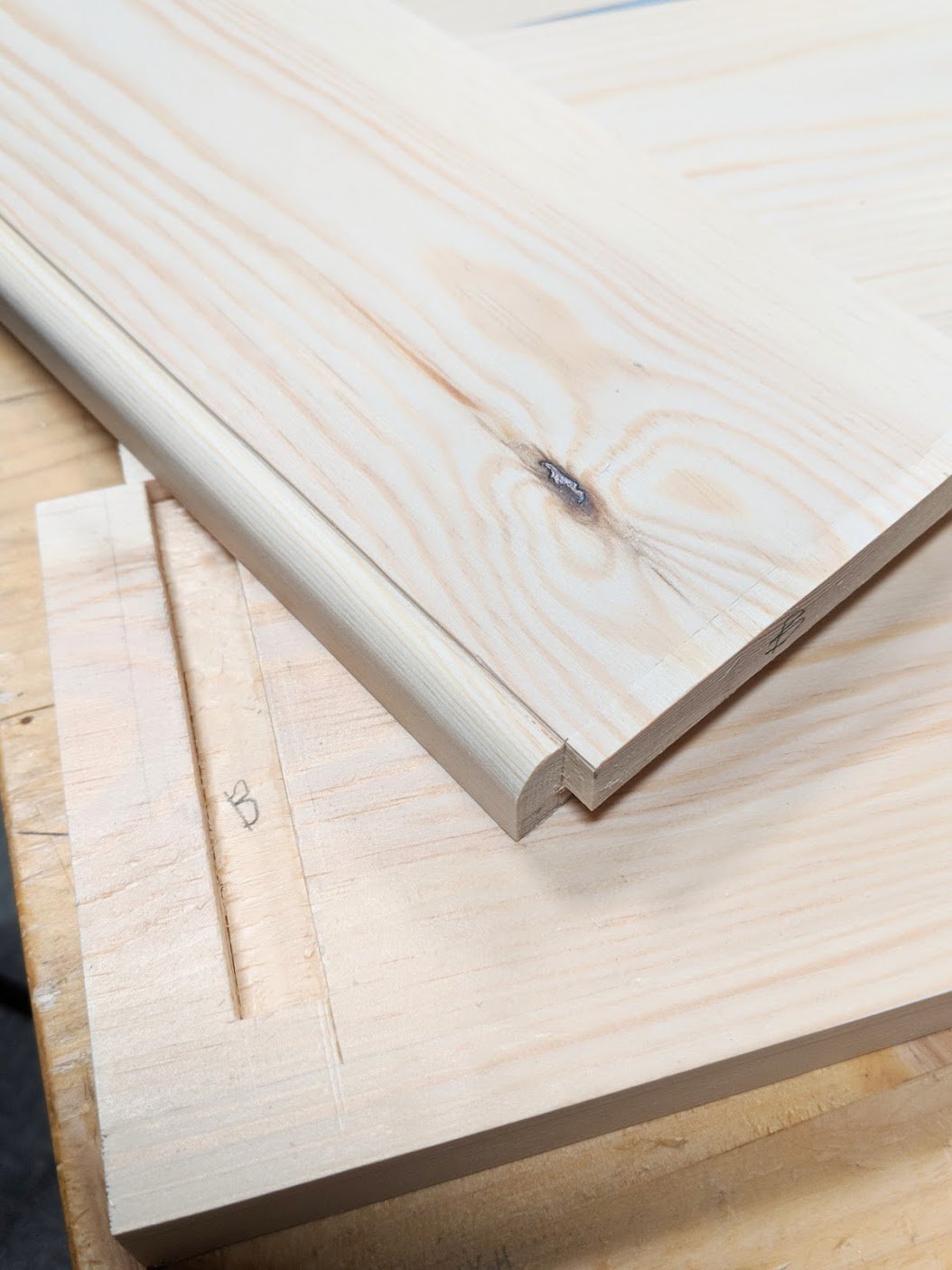

Stopped and stepped housing dadoes hid the front edge of the joint line so as not to draw the eye. The through type is not at all a good looking joint. Not even particularly mechanically strong. Without additional joinery in support, the joint offers little lateral stability. What the joint does do well, better than any other really, is it bears downward weight exceptionally well. Masses of it. I think we can all relate to the housing dado more as the bookcase joint than any other. That being so, and the fact that few materials in home and office weigh more than paper, its load-bearing capacity is well proven. Think of a five-shelf bookshelf unit three feet wide and you begin to understand the accumulated mass of weight bookcases are expected to withstand. Push the top of the bookcase laterally from one side to the other and there is almost no chance of moving the bottom because of the combined weight the books send to the two sides either side. What you will do though is you will easily break the glued joint lines at the bottoms of all the dadoes. Ultimately this weakens the whole piece. So we see that what this joint does best is it takes on dead weight. That's mostly where and why we use it. In my work I generally combine the housing dado with some other type of joint. At the backs of drawers I use it with through tenons or sliding dovetails. For bookshelves I use through tenons in rails to undergird a middle shelf. This is what we joiners and furniture makers consider when we design a piece.

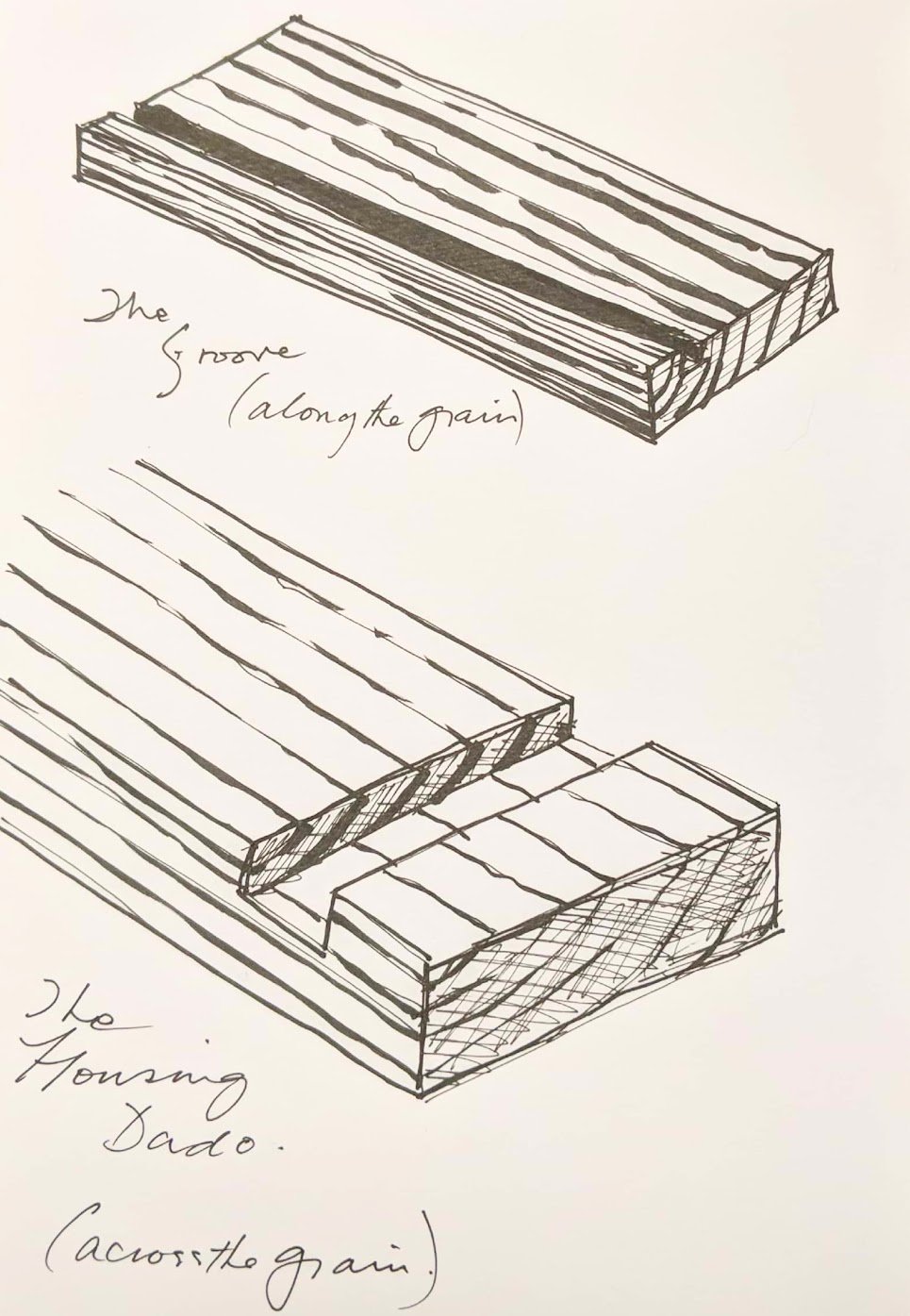

Identifying a Dado From a Groove or a Housing

In the UK the use of the term dado is less used than in the USA. Generally, the Brit's use the term housing or housing joint, but this term can be used so broadly that it sometimes fails to specifically identify what would benefit us. I discovered dado when I moved to the USA and it made sense. Whereas a housing joint can go with and across the grain, in the US dado is used for across the grain channels and grooves go along or with the grain. Simple and descriptive. I named the joint differently to better define it and to connect the two countries (two countries divided by a common language) as a compromise but the compromise really works without diminishing anything at all. Hybridising housing with dado tells me and others that it is an across the grain channel. A groove needs no further defining and then a housing makes great sense for with or across the grain and is used for recessing mostly, be that then to receive the end of a section of wood or a piece of hardware.

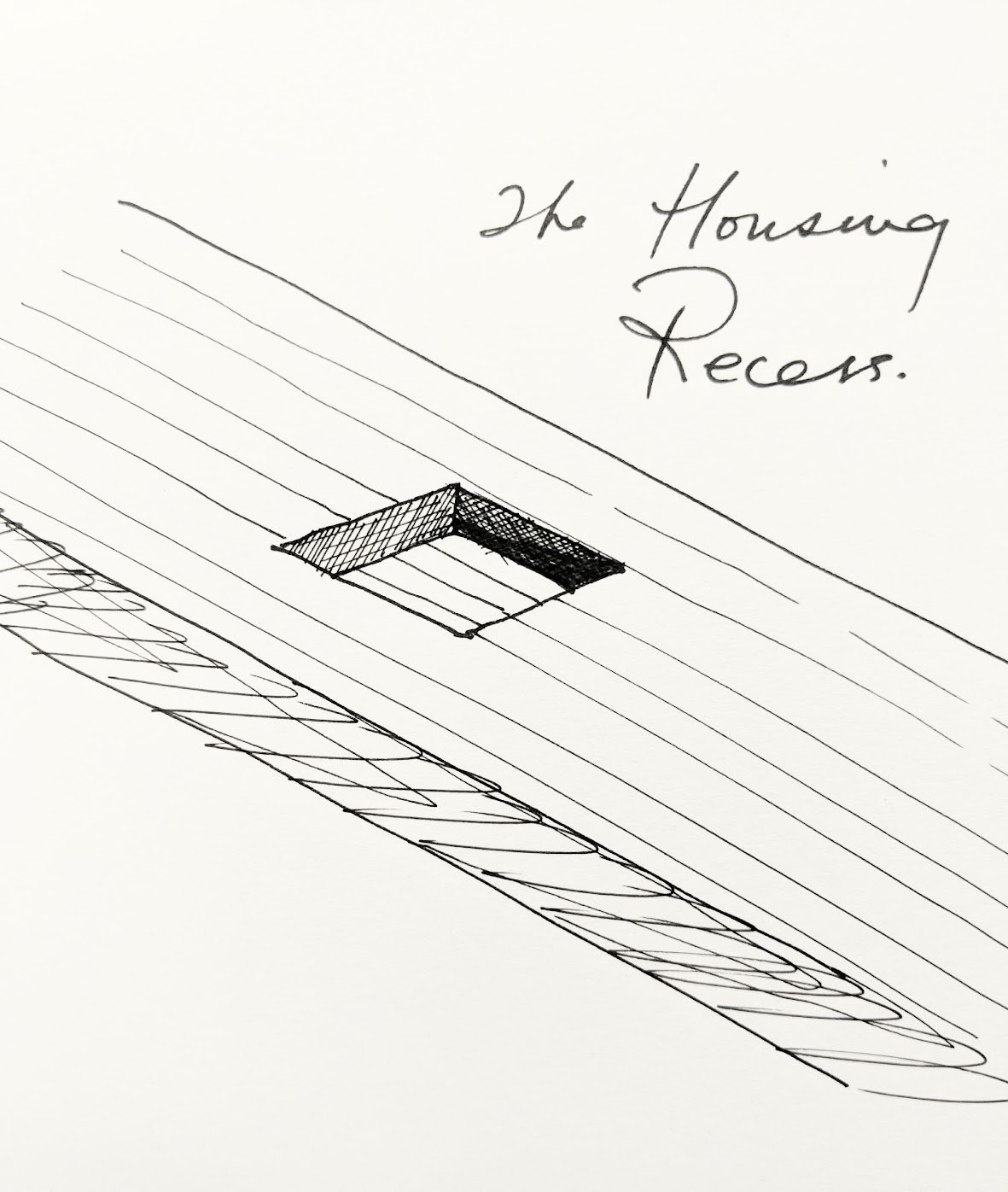

The Good Reasons For Stopped and or Stepped Housing Dadoes

One, the shelf might shrink at a different level to the adjacent receiving members, the shrinkage will not be visible because it's behind the stepped part. Remember that these joints were developed centuries ago when the only way to really measure moisture content was by local knowledge of local atmosphere and the local craftsman knowing his stock wood. He knew how long since it was cut and how long it had been drying, give a year or two. Today we can use a moisture meter or weigh the wood over a given period to see if the wood is stabilised or increasing or decreasing according to the atmosphere we live and work in.

The second reason for using stepped housing dadoes is we can shape the fore edge of the shelf or shelves so that as it butts into the adjacent housing piece the moulded fore edge isn't left unresolved at the meeting point. Yet another good reason, the third, is where a stepped housing dado is used in conjunction with a stopped housing dado and the fore edge of both shelf and adjacent housing pieces are aligned without any step back. This gives a clean and crisp line to the joint which is hidden inside the wood.

Often the stopped housing dado allows us to set any inner shelves back from the fore edge of the main carcass to facilitate hingeing a door within the the main outer carcass.

Comments ()