Beyond George

The ever important element to my life was and has always been the constant moving forward in my craft. I read all that I could and went to where I needed to go to learn more. There was no world wide web and all mail was delivered by had through a letterbox. The library was restricted but there were specialist book clubs that sent out catalogs every month for you to choose from. Events of consequence were haphazard but things did get more organised with groups forming based on like mindedness. I enjoyed Bill Goodman's book on the history and development of moulding planes followed by the Village Carpenter. Even so, I always sensed there was more; there has never been a point of having arrived. In fact, completing my apprenticeship was immomentous if not trifling. Its significance seemed only to be recorded in my wage being increased to a man's full wage. I was paid the same as the other men around me. The papers surrounding my being indentured as an apprentice were signed and returned via the post. It was over.

Every point of change is simply a stepping stone to something new. Learning your craft is an unfolding continuum into new future. To see it as less is to stunt your growth and side step your personal upskilingl. Whereas I am grateful for the dedicated years where without financial pressures, developing extraneous relationships, I could begin to own my craft. My apprenticeship seemed to me to be more the equivalent of my learning to read and write in school. Writing sentences comprised basic grammar, learning to spell and understanding that it was, like talking, a basic form of communication. At the end of my formal education, being programmed to make sense in structured sentences, I see now that it mostly provided a skeleton—a framework upon which to add flesh in the form of muscle and sinew—substance that conveyed meaning to others. I'm not at all a writer. I am a woodworker. My apprenticeship was merely the skeleton. The punctuation of interconnecting junctures where change of direction comes in sentences and paragraphs. It was only after my apprenticeship, knowing the sizes of components and the stability of different woods, understanding wood and tools and the union of will and problem that my life as a craftsman became the culture I could truly immerse myself in. Just as I faced the issues of structuring sentences to communicate, I found myself communicating my inmost feelings for woodworking and craft work as a whole through what I would make. It was here that I found myself moving readily and openly into an ever unfolding future.

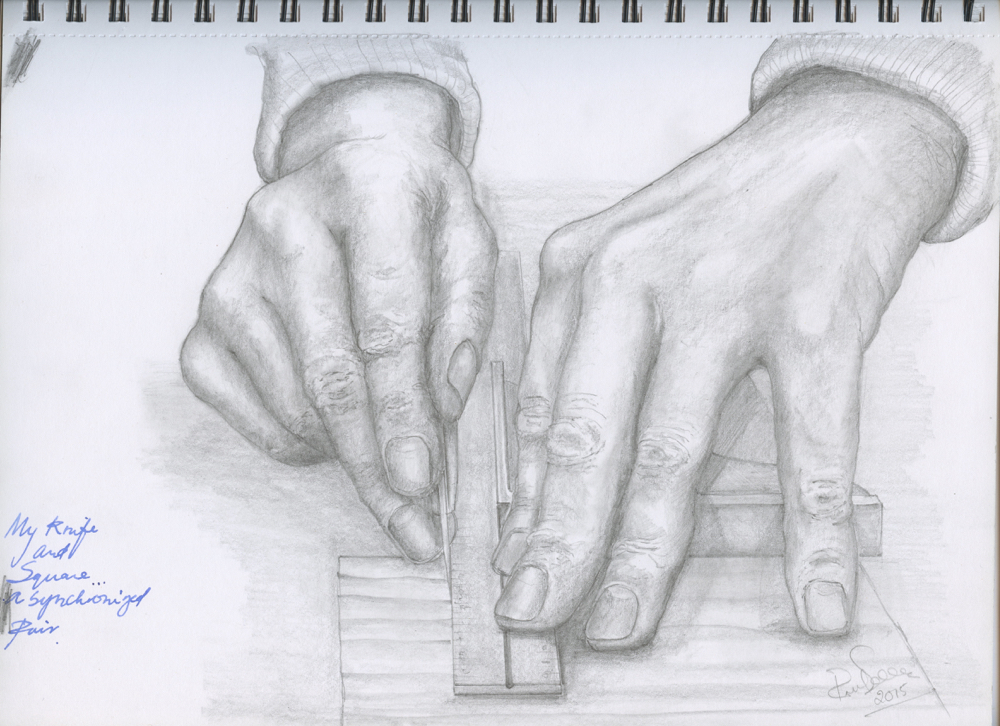

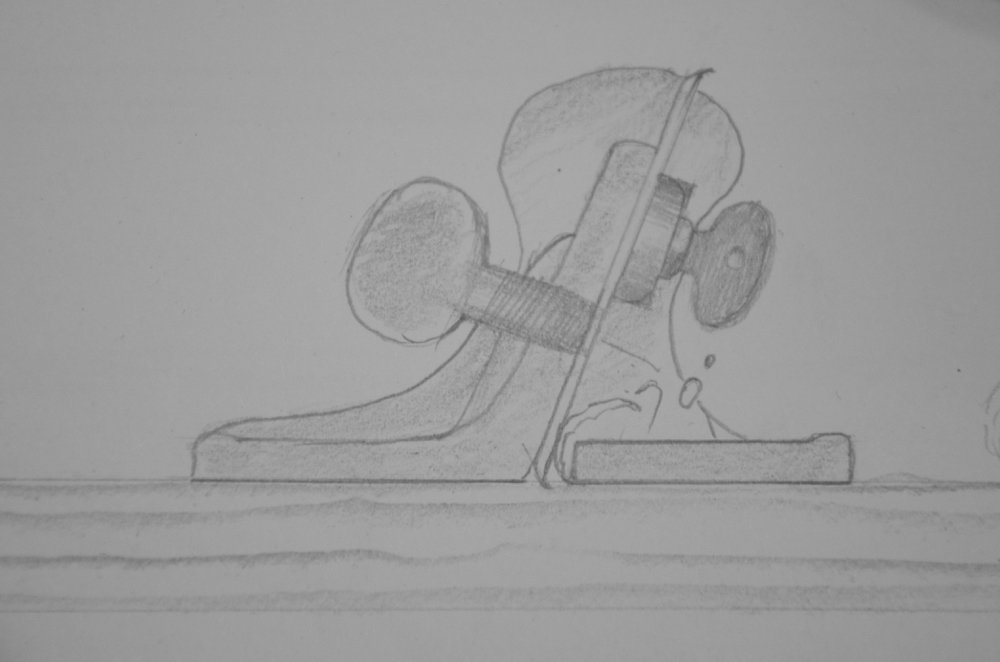

In woodworking I discovered the sciences. Biology made great sense to me in the photosynthesis in a leaf, the porosity of certain wood types over others. Things like that. I discovered mathematics and physics in leverage for lifting and shifting pressures, transferring energies, controlling direction. What made no sense to me in school made great sense in work. In woodworking geometry became fascinating as did private lessons with George at the bench after every question I asked.

In the beginning I found the pen awkward to hold. Dipping the nib into the inkwell seemed always to overload the internal reservoir of the nib and that always resulted in what was called an ink blob. The Bic biro came into being but of course it was an inexpressive substitute resulting in the kind of standardisation schools seemed to love. Despite my intermittent ink blobs, my dip pen gave me the ability to express my inmost feelings. I rediscovered the fountain pen 30 years ago and never looked back. I shook of power equipment when I decided never to mass make again. It took some dismantling because OI had lost the exercise hand work demands. After three years or so all of my understanding of why I loved woodworking returned to me and I fell back in love with my opening experience of woodworking. In a sense I found my first love of woodworking still waiting for me. This was to understand the significant purpose of exactly what vocational calling was. It wasn't at all where you sent the thick kids who couldn't maker it in a more academic clime, it was where any kid could actually determine what they really wanted to achieve in their lifetime. Crossing that line enabled me to never work for money again. Money was the insignificant ingredient and not at all the driving force behind my work. I never worked to develop an idea to make me rich again. I never became rich in money, I became rich in relationships in a growing world of likeminded people, not just woodworkers, who wanted to become significantly skilled. Every video we have ever made comes with maximum forethought. What is best for my audience. What can I give that will make them grow, experiment, investigate, search and seek what has in fact been lost to the age of technology that seems always to be the resource people turn to for answers.

Many things that I make hide the reality of my struggles. Most people never see the work it takes, sometimes the agony, the self examination, the inner battles. Have I hit the mark. The last thing I want is to pad things out. The last thing I want is to hide anything. You know, speed up a process by using tablesaws and routers, such like that. The last thing I want is sponsorship by some giants. The last thing I want is to compromise my work and my freedom to be forthright. Manufacturers want me to use their hand tools, but the ones you see me use in the videos are the ones I bought from somewhere. High end ones too. I'm researching bandsaw blades at the moment. I buy them. The makers offer them for free. Hundreds of pounds worth, but I buy them. Hand tools I usually buy anonymously. Not always but I always because the sellers may know me, but I always buy at full price. I never feel compromised this way. I stopped writing for the magazines for the same reason. An editor of a magazine once said to me, "No, we don't want a full article from you, we want short sections of an article in pieces so that people keep coming back." I never wrote another magazine article. I started blogging instead.

So between blogging and writing my books, making our own videos instead of for others, I live my life in the style I have engineered with the help of several others who support my work. It's a freedom to life an expressive woodworking lifestyle. The shelves that hold my tools and things are real. Nothing is placed for effect, nothing decorative or designed to lure or tease. This is my life.

I have more to write of my life under George. I do this because it undergirds my early beginnings. It's the foundation of me as a woodworking craftsman. Where it ends I will not know yet. Perhaps I never will until the very end.

Comments ()