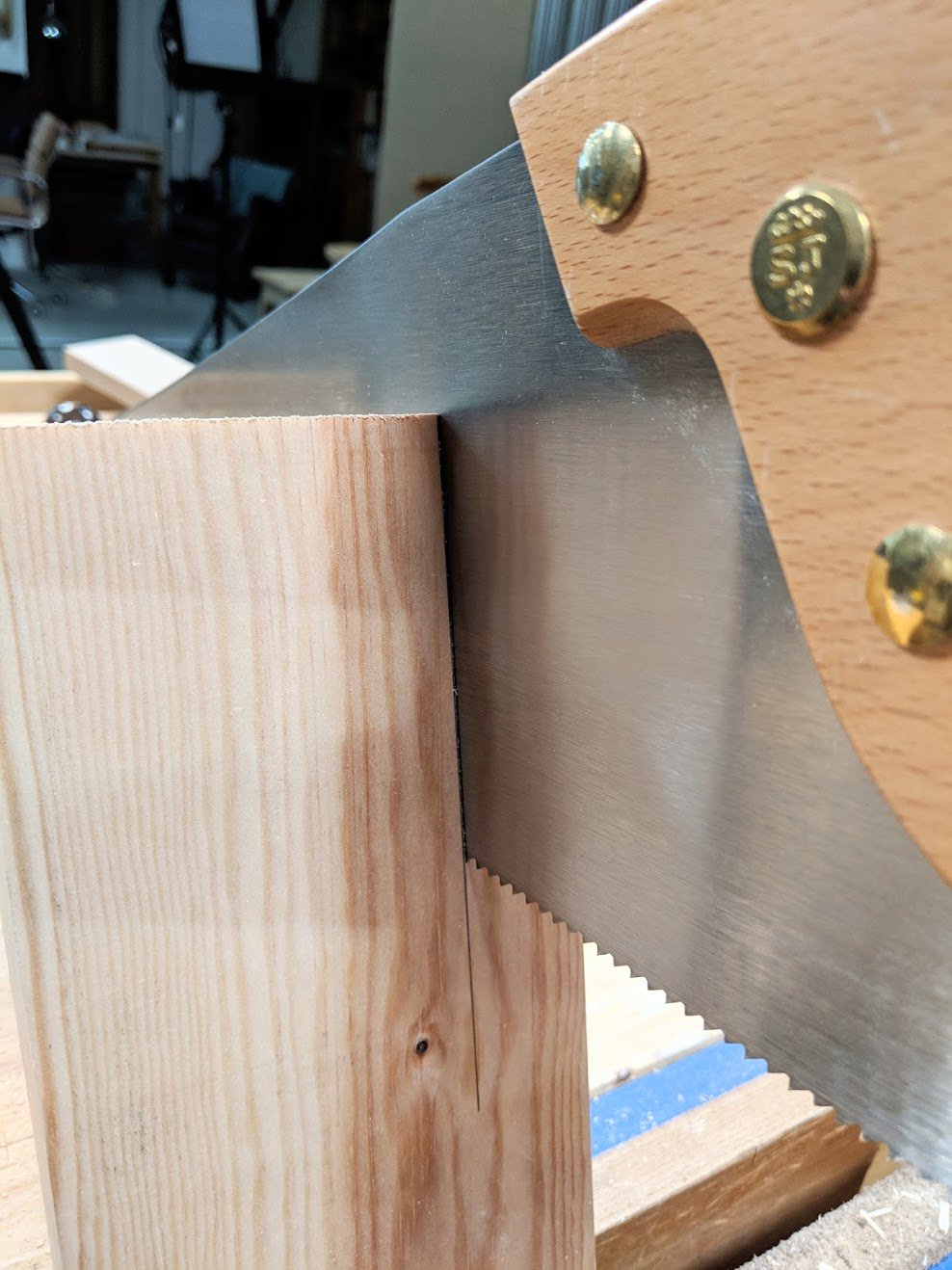

Can't Saw Straight—Practice More Often Before You Begin

Saw won't cut straight, man can't cut straight, wood won't cut straight...

I think most people, young people old people, those in between look at someone sawing and think to themselves, I could do that; it's just manual labour after all. Not much to it. In the cut they find it's not quite so easy. The saw wanders, tilts and it won't cut square. Realisation hits and they usually give up, not necessarily always thinking it's them but blaming the wood and the saw. But sawing is an art and it's quite an art at that. If all of the coordinates are set right chances are you will still drift if indeed you are a novice. Sawing takes practice and that practice should be applied to every saw because no too saws are exactly alike. Add to that that no two woods, even in the same species and from the same section, are alike too and you begin to see that the diversity of permutations means you must be prepared to alter your attitude each time you pick up a saw.

Sawing demands self discipline that requires ongoing practice, which means picking up a saw as often as possible and not substituting with power equipment to dumb down your skill development. Taking a week out from woodworking means that you may need to have a few practice sessions in advance of your stroke work with a saw ahead of actually applying the saw to a project. Entering the zone this way reacquaints you with your saw and sends the right signals to your brain for processing. We don't consciously think about things this way but this act actually begins the flow of released chemistry through the brain. Personally, I use my saws minute by minute every day. Scarcely will ten minutes go by without me plunging the saw into a dovetailed angle or a ripsaw down the length of some board. I say this with my bandsaw standing next to me. Those new to woodworking and then those who use hand tools less frequently because of other work pressures may not realise that their work suffers when they don't practice the art of actual hand sawing.

In my view it is a question of practice through exercise and it is no different than when singers train their voice, or the violinist strokes the bow on their instrument. Why should it be any different than an athlete training every day for prolonged periods to engage in competitive sports? I have experience the need to 'get in shape' every time I take a week or two out. It's amazing how the little nuances of sawing that give expected results get lost when we neglect practice by doing. It's also amazing how people of every walk think that they should automatically be able to perform these simpler manual tasks with certain ease because it is to them a low-demand exercise requiring no thought but just action. A friend of mine is a rowing coach. He's 60 years old and he himself practices many days in a given week. Why? "I have to feel the water with the oars, If I do not I am 'out of sync'.

On a regular basis someone contacts me to say they can't saw straight. With those new to hand saws of any and all types, from dovetail saws to 4ppi rip- and cross-cut saws, they almost immediately blame themselves. Whereas of course it could be them, it's not always. Even new saws have issues and that includes some of the high-end ones. Saws are often at their most aggressive when newly sharpened and can function more amiably after the first hundred strokes. Whereas a newbie can exacerbate the sawing issue to worsen the situation, often it is indeed the saw itself too. Too sharp and not sharp can present issues. With new and well sharpened well set saws it's a question of conditioning yourself to be less aggressive and heavy handed. Until we are indeed used to the saw we tend to press hard instead of allowing just the weight of the hand and the forearm apply the exact pressure and focus our attention on the course the saw needs to take. I thought this might be helpful for the self deprecating. As I said, it is definitely not always you!

Then, on the other hand,how often have seen wanna be carpenters thrusting handsaws into 2x4s mindlessly at the big box stores and watched the saw buckling under every thrust. They throw the saw down with heartless cursing, never seeing themselves as the problem. Used to power equipment not handsaws they draw their conclusions. They began with an attitude before they picked up the saw and concluded that they were right.

It is no doubt confusing and frustrating too when the saw does seem likely to drift and wander back and forth from the line; it demoralises your ambitions. It happens to all of us at one time or another though, I know that. What did we do wrong? Well, some times it is our fault, of course it is, but sometimes it's not ours at all. How can you tell? This is what practice is all about. Mostly it is to familiarise yourself with the elements engaged with. The saw, the wood and you. Saws respond differently in wood when say sawing a 1 1/2" thick piece over a 3/4". The growth rings on woods like pine, that have hard and soft aspects to each growth ring, can 'lead' the saw to a less resistant course. add to that a dozen or so other influences and you begin to understand the dilemma. Practicing to begin each session will help you in all areas of your understanding. Taking this time is the equivalent to say limbering up before athletic sessions begin. Go ahead, kick the ball around a little!

When the saw binds in the cut stop, stare, look at your body position and see how things are aligning. Ease up, lighten the hand, feel for where the saw lies and make those micro-adjustments to the saw. A bulldog attitude rarely works for us. `we have to feel inside the saw kerf to make our bodies respond to what we feel rather than what we can see as we move. A binding saw always highlights that something is wrong. The problem can be one of a few. Wet wood, misalignment, poor set, uneven sharpening, worn teeth, unevenly worn teeth, buckling in the saw plate, a kink. That's the saw alone. Within each example there can be multiplication,. Take saw set for instance. An overset saw usually does not bind, but it does allow the saw to choose an alternative path of least resistance. Remember the example of pine above for instance.

Comments ()