What's 'Knifewall'?

It's just a more active word when the two come together—less passive without a hyphenation. I like knifewall because it's more punchy, but really I like it more because it so describes what I want people to see. It's 20 or so years old now, not much more. It's not that I invented its work, more that I defined the result of using it. Knifewall didn't exist when I thought it up, started using it and then penned it, but it isn't all that easy to come up with something you can actually name and then go ahead and name it. It was a knife cut and a crossgrain wall side by side. Why not bring them together? Unite them?

So there I was, looking at my knifewall and standing in front of 20 students when, right out of the blue, I just said it. 'KNIFEWALL!' I said it again and then again, to solidify it, you know, and, well, it just fit. I'd said the word knifewall for the very first time and it meant exactly what it said. It was made with a knife and the knife made the wall you see. So I coined it, the word 'knifewall', in the absence of an accurate term, to take its rightful place in the vernacular of woodworkers. Cutting that knife line and sharing the new term with others meant something significant. I should perhaps have coupled it with another word I used at the same time, shoulderline, because 99% of the time the knifewall creates a shoulderline, which is the intersecting line creating that critical juncture between two pieces of wood.

I don't know if any other craft develops such a physical wall this way, it doesn't really matter. Knifewall says it just the way I said it and the way I wanted to say it and no other word or phrase exists that gives it such succinctness—certainly not 'make a knife mark' or 'strike a line'; two terms I heard in school as a boy at thirteen—hence 'marking knife' and 'striking knife'.

Back then they did give us "striking knives" with 6" long points on, alongside pencils, to work with, but neither pencil nor striking knife gave us what we really needed; neither could give us the parting off we didn't know we wanted. It's also something that back then we may have feigned stabbing or lunging actions playfully but it never entered our psyche to actually injure someone. What changed?

For my craft, woodworking of any and every kind, it's wood that demands the definition because wood generally has unidirectional grain. The grain develops following the longitudinal aspect of the tree's growth as it follows its up-reaching growth toward the light and warmth of the sun. Just as surely as the word apricity has value in describing this action of being 'warmed by the sun', though not used so much any more, the term knifewall describes cuts across the grain to prevent the wood's surface fibres from ripping and tearing because it's counter to the course of the tree's grain. When other cutting-edge tools follow to advance deepening cuts adjacent to the knifewall, the knifewall serves both as a guideline and a line for other tools like chisels, planes and saws to register to. Thus the knifewall becomes both the guideline and the wall that separates the waste from the wanted.

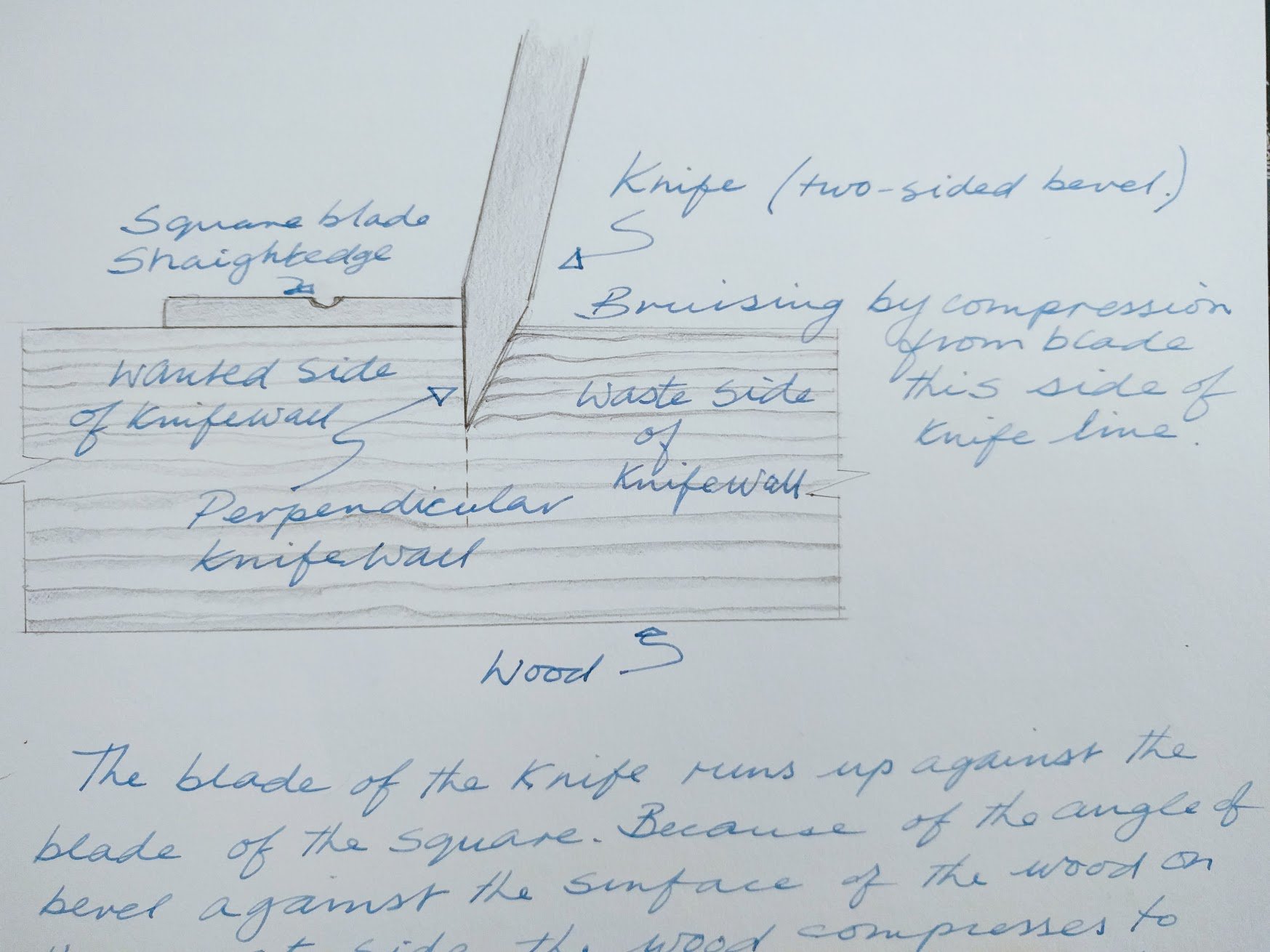

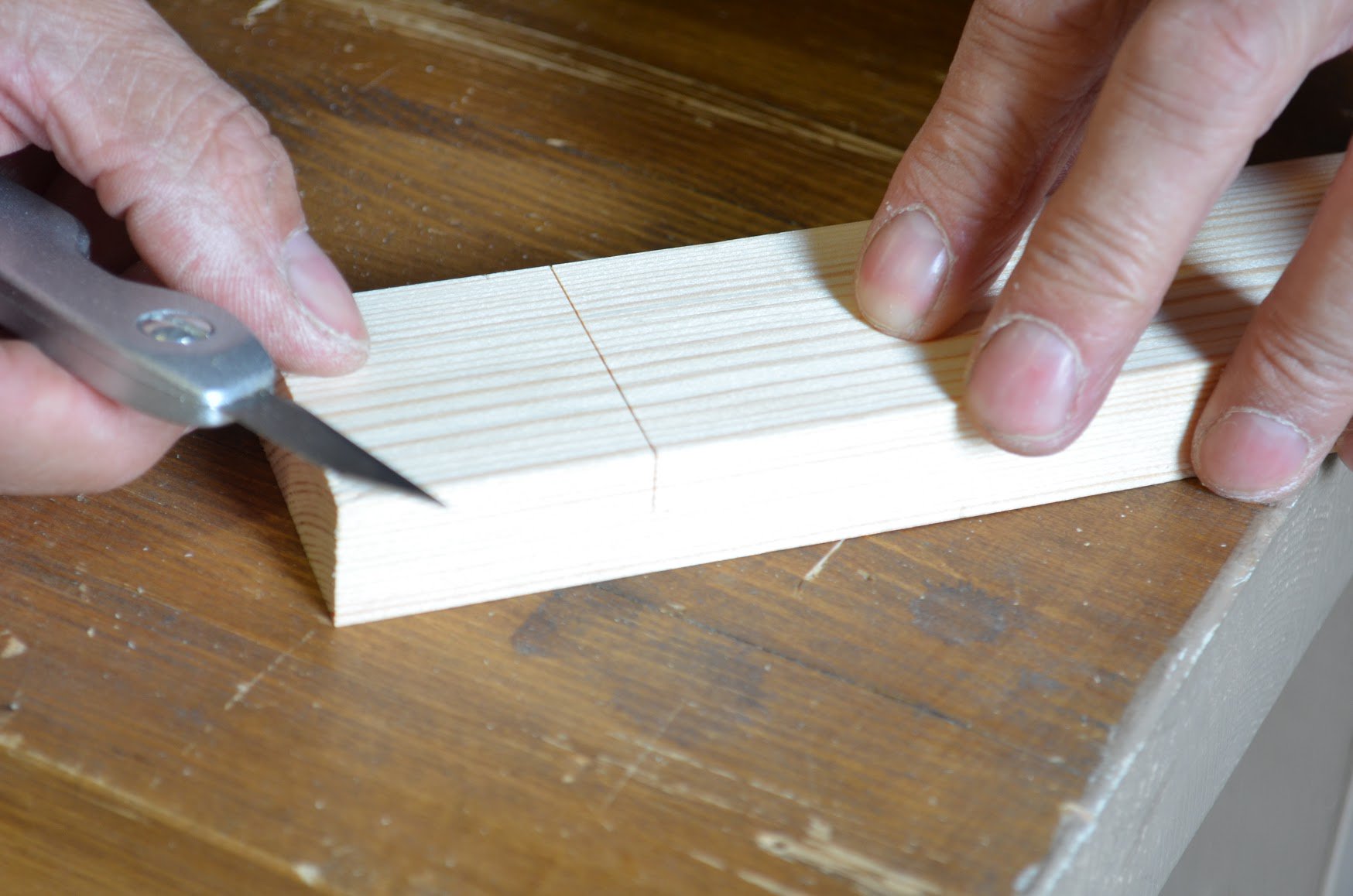

Note: One thing that often takes a little while to understand and register surrounds the issue of bruising from the bevel of the knife: that this should be on the waste side of the wood, and therefore that the knife be held so that the bevel rides against the square in a deliberate perpendicular presentation. This then means leaning the knife slightly to one side. I think the close up photo at top shows this well enough, and helps cement this idea by seeing it from this angle. The result is shown below.

In contrast, the knife mark was relatively under-defining even though the square would be placed dead in the line or mark. Impressing a less than sharp knife onto the wood's surface leads only to the knife scoring the surface rather than a severed knifewall. This then develops more a trough-like indenting and one incapable of severing the surface fibres as happens with only the very lightest pressure if the knife is truly sharp.

The fibres compressed thus along the line both to the side of the square and also beneath its beam, develops only a 'vee' channel and no true knifewall at all. For some work this would be adequate and permissable but to develop cut lines leading to perfectly closed shoulderlines it's not enough. Woods with contrasting density surrounding growth rings, pine, fir or spruce for instance, leaves the line undulating as the wood compresses at differing levels across the width. I say this to avoid confusing knife mark with knife nick as the nick severs and the mark indents.

After many years of my using the knifewall, decades, I began teaching others the method the same way because it did indeed seem to be the missing link between the pristine accuracy we saw in old work and what was coming from the hand tools of the day. I had taught myself the method of combining the knifewall with a chisel cut angled low toward and into the knifewall that thus created the slight step-down I needed for saws and chisels to register against. The step meant that the shoulderline could be progressed deeper into the sub fibres of wood being cut.

I wanted something that would replace the term knife mark because, well, knife mark just did not quite cut it. It was teaching that changed my consideration of how we approached the creation of good joinery by hand. Such was the reality that many things ordinary to me needed a boost to a new level. The commonplace things craftsmen often took or take for granted, like 'knife mark', needed a reality check. Was 'knife mark' right or did it need a brand new word? It did!.

Mark just did not cut it in the way I needed it to. Mark meant more to mar rather than slice-cut crossgrain to the long axis of the grain of the wood. Something had to redefine what was taking place because the shoulderline markings we did in school with a pointed piece of steel or a dull or dulled blade seemed far from being an apt tool for accurate levels of workmanship, not at all what a craftsman needed. I could never mar the wood with a broadish bruising stabbed at a position. What we needed was a definitive cut line parting off a pristine wall and then too something that definitively said exactly what it was—knifewall!

Crispness is critical to shoulderlines, so to develop that level of crispness meant developing an attitude towards sharpness and sharpening. The term has become more commonly used for defining the work itself.

Whether it will ever make the Oxford or the Merriam Webster dictionary requirements remains to be seen and is perhaps doubtful, but woodworkers around the world use knifewall in their work today even if they only need to say it in their heads as they work!

Comments ()