Just Some Thoughts Surrounding Saws

I bought a panel saw on eBay just recently. The plate steel it's made from is quite thin for a western saw, but it's thin on two counts; through maker design first, and then long-term wear. And it's plate tapers too, like the more modern taper-ground saws of the 1900s, but this one tapers by wear not from its making. You find that in older saws, you know, 'thin to back' but not manufactured that way at the time. In this case the saw is indeed tapered by redirecting the saw in the zillion cuts it made, which causes wear on the sides and top edges of the plate through a century or even just a half a century of daily use. Anyway, at .68 of a mil at the thicker part, and then with a spring steel resistance factor I have yet to find in any modern saw; in use it has just reached perfection itself.

Experience tells me we're unlikely to see innovative changes for better handsaw making not even in replication of the levels of what our forebears left to us. At least it seems that way for the foreseeable future, but I am open to possibilities. I see backsaws being better engineered than the low-grade versions British and US makers stooped to after the 1940s by the key makers of that era. The ones living off their founder's reputations who shamefully introduced the new plastic-handled versions using low-grade standards of manufacturing and quality. Most higher end back saws on the market are replications copying old models from the 1800s. I suppose this to be because the quality of old back saws was so utterly good. But as for handsaws, no one seems to want to touch them for some reason. So thankfully you can still buy good quality secondhand ones for reasonable and even bargain prices if you are not in a hurry. Often they go for much less than half the price of the newer versions that don't really come near to measuring up. I would like to see just one of the modern makers (course there are really too many around) step out of the risk-averse safety zones and take on the challenge of making a set of really good handsaws. Anyone can make a back saw, but not everyone can make what I speak of with regards to handsaws. I'd like to see one of them do the research, do the experimenting as those must have done in the 1700s, and come up with saws not too thick, not too thin. Ones that don't wobble too much in the cut or then buckle under the slightest pressure too. Who is the man or woman up to this? I still do the research and come up with new ways of working, even after 50 plus years.

Cleaning, restoring, sharpening and setting

Well, anyway, I took a little time to clean off the light surface dirt and the hint of rust on the plate came with it. Thankfully there was no evidence of any pitting in the plate. I probably would still have bought it because of the rarity of the saw, but I was so, so glad it came up for sale. Good old eBay! I really don't like pitting, even if it makes little noticeable difference to the functionality of the saw in use. It's just looks, I know. I wanted this saw because it concludes my gathering of like saws by a like maker I respect. Probably I would not have wanted one that wasn't so well used and worn as this one was. Whereas I like other makers too, especially those that set the standard in the 1800s, Philadelphia Disston, early Spear and Jackson and others, once you find a maker you like you will gather your own preferred models.

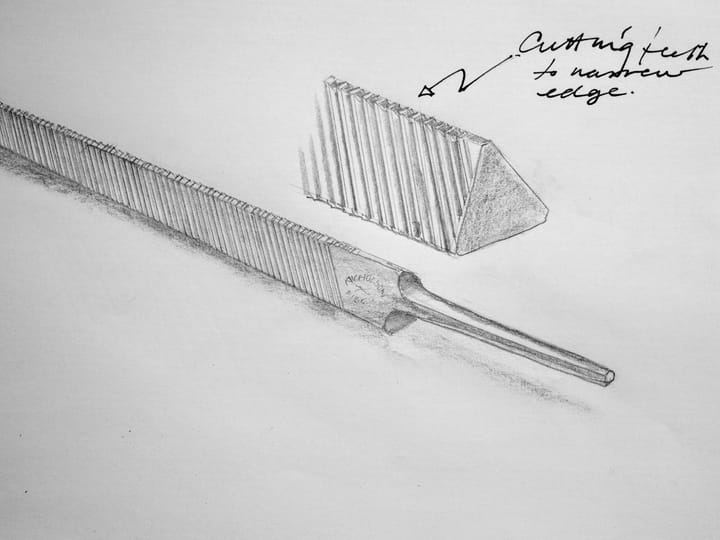

The teeth were a mixed hybrid of composite tooth shapes. Some cross-cuts others rip-cuts, sporadic shapes side by side, which I hadn't noticed until I used it and examined why it would cut nothing. I enjoyed the challenge of redefining and reshaping the poor things. It felt hard and harsh at first. The heavy grind on some, topping (jointing USA) was essential to remove the unevenness and the resultant undulations that so trip up the saw in the cut.

Comments ()