The Mary Rose Exhibit Makes Sense of History

Sunday 16th April 2017

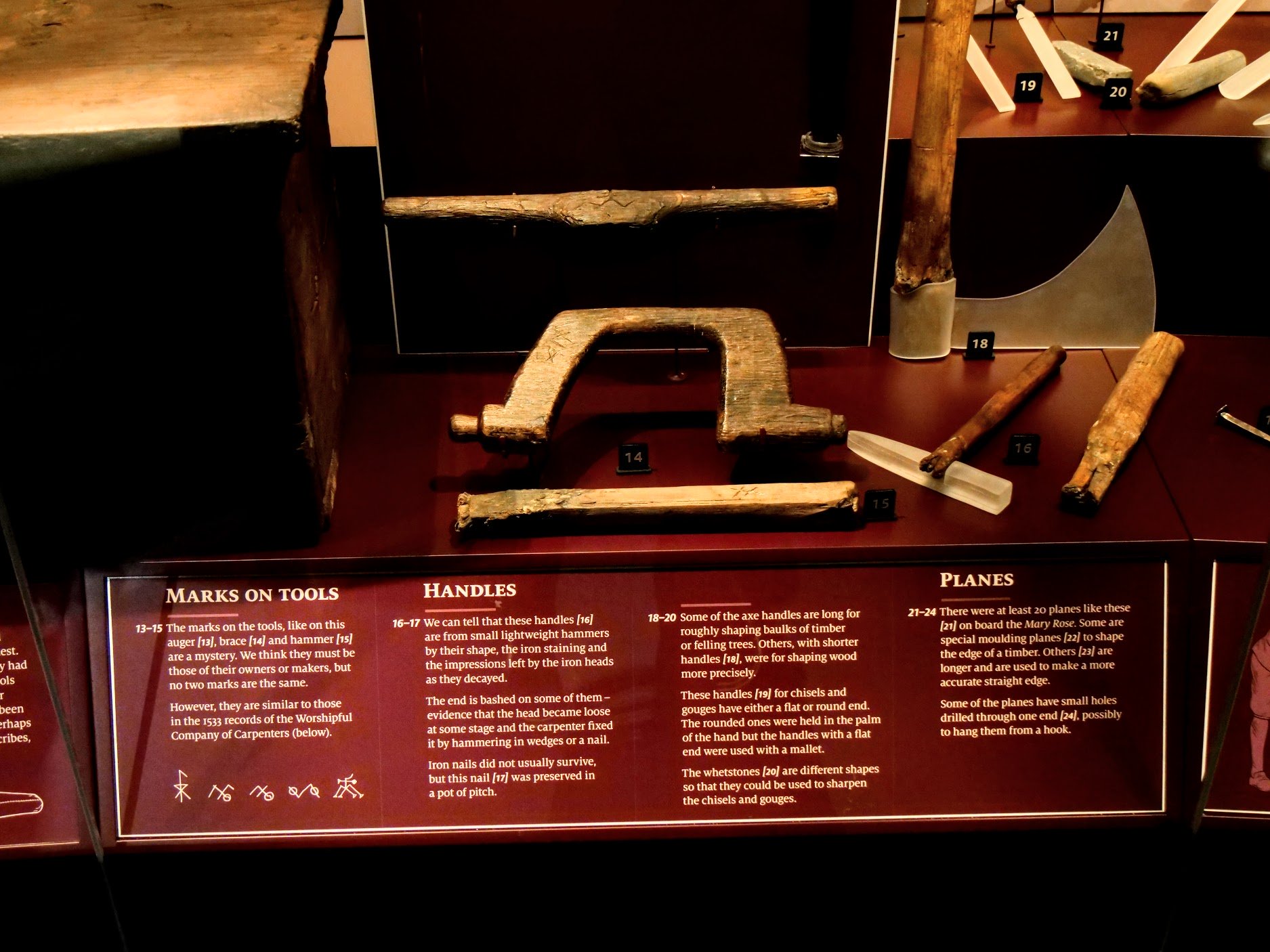

Most metal had long since corroded in the rigours of a corrosive salt washing of 5 centuries or so, but handles are almost always obvious. Combine that with location and the pieces literally come together. Had it been for me to be a part of the discovery I’m sure I would have had many sleepless nights. But the museum for me was as much about the living as the dead. I enjoyed watching the reflections of children’s faces in the glass as I did the encased artifacts. They took in the shapes and colours formed in wood and steel, bronze and copper like sponges. What it all meant to them I am not sure. Try comparing a bit-brace and centre bits blacksmithed in a forge to our now more ubiquitous modern-day battery-powered drill-driver and you might glimpse what I mean. Parents seemed to me once again the result of our modern analytical age where nothing shown reflected any experiential knowledge; nothing really related even to the older parents with the children. Skip two or three generations where handwork is gone and relational knowledge disappears. The new generation can then be forgiven for thinking the old ways are indeed old and inefficient when in reality they worked efficiently and effectively. What they didn't do was keep pace with a mass manufacturing society if industrialism. That did not mean what was did not work. Nothing of the sort. That's why what I do today really works if indeed people have a mind to open their hearts to its reality. You see, even what was written in the legends at the Mary Rose museum to inform became lost information to the child because it wasn't really explicit enough. Add to that that ordinary leather shoes hand shaped and formed and stitched together by a man's hand became "swimming flippers for underwater swimming", according to one dad, and to another axes were "weapons of attack and protection" instead of dressing tools for trimming replacement sections in the repair of a cannonball holes in the ship's hull.

I wasn’t altogether sure accepting of why plexiglass was used to replace steel auger bits and saw blades of steel and why some got the treatment and others didn’t. Visually it did work for me but without clear explanation a child might not make the correlation between our plastics of the 20th and 21st centuries and metals of the 16th lost to corrosion in seawater. So I am sure a note or two more of explanation interspersed here and there would have helped.

Considering the lowlight my images came out fine considering also that no flash or tripods were allowed. In actuality, with a little enhancing, what I could not clearly see with the naked eye because of darkness I could clearly see at home. The show-cased goods were nicely presented and protected. Even so, I would have liked to hold some of the pieces to feel the weight of the wood, examine it and then go on even to replicate some of them to better understand the workmanship, workability and the tools. It’s surprising how much more I could glean from handling the pieces and examining the tools with them actually in my hands. As a working craftsman I am sure I might add further to the discoveries to complement what was indeed fathomed under the microscope as it were.

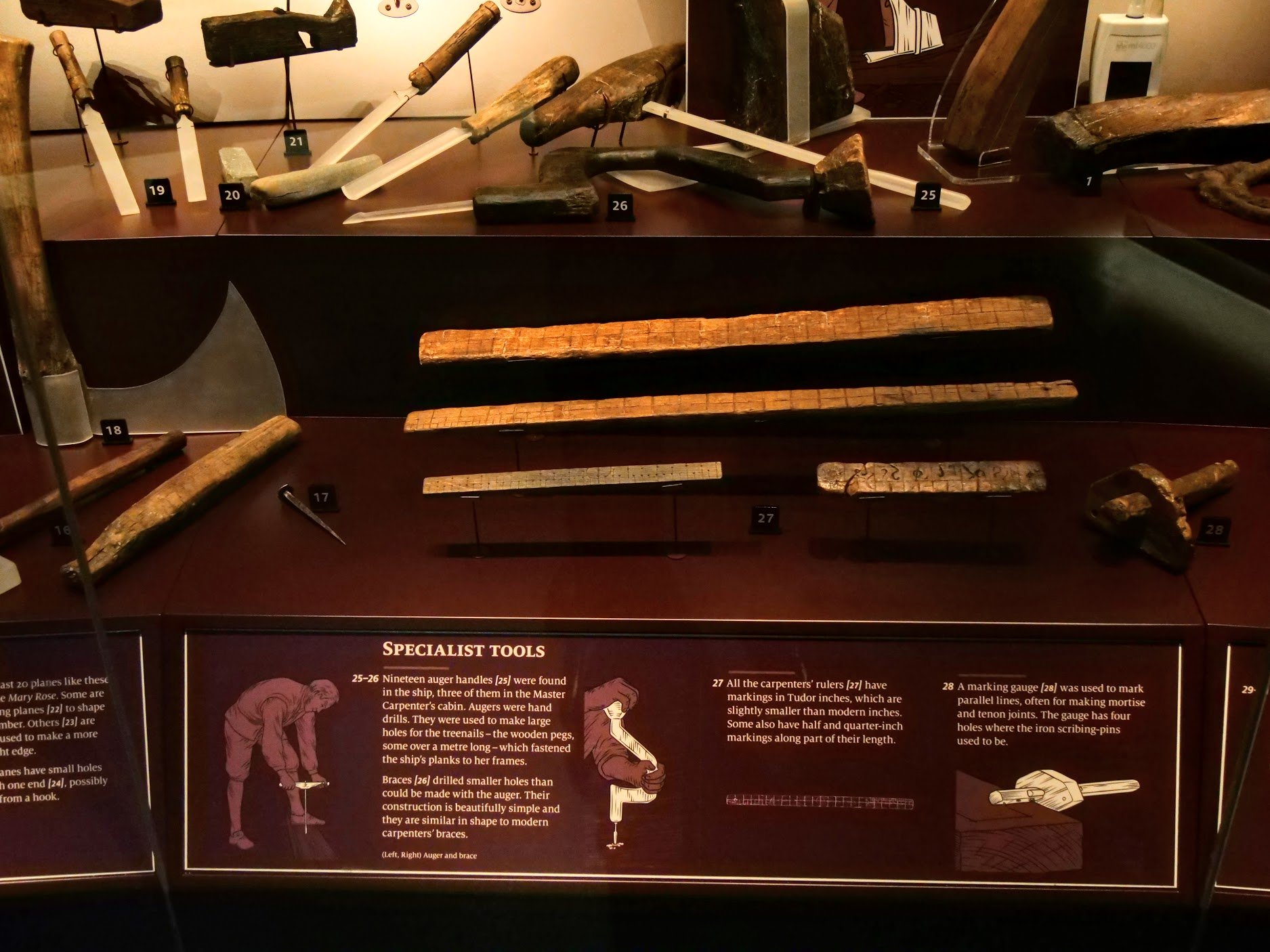

Look at this plane as an example. It tapers from the centre, becomes thinner at the four end and then has the handle, which looks like it was a branch from the main tree stem, coming out toward the stern end. What a fascinating concept! The large knob at the fore end looks more like a bung. I wondered about that too. Knife handles were interesting as were saw handles, I learned that a Tudor inch was slightly less than a modern-day inch.

Much use that is when only three countries in the world use imperial measurements today, Liberia, Myanmar and the United States of America, but interesting. Mostly the rulers had only inches with no in-between markings, so i assume ½”, ¼” and less were gauged by eye. I actually still gauge most measurements under an inch by eye. I am not sure if as much woodworking is contained in any other sphere that shows the diverse skills of the carpenter. Wheelwrights to ship wrights and coopers and cabinet makers lived and worked alongside one another, adapting their skills and knowledge interchangeably for the betterment of those on board.

You can’t help but place yourself in the tormenting whirlpool as the great unsinkable was enveloped in wind and water. What was found in the bowels of the ship might well have been worn out by life had it not been held in the watery time-capsule of the deep. A hundred yards from the Mary Rose is HMS Victory–two hundred years its predecessor, whereas across the docks is the modern-day warship of our era, HMS Diamond. Reputedly one of the most advanced warships of our time.

Comments ()