What Went Into My New Book?

Question:

Hello Paul,

I would be very interested if you'd share a bit on what you did put into this work. I mean the content of it, of course, but also what your intentions and thoughts were as a writer .

For my part I started as a writer and illustrator and now after a couple of years of following your courses I’m becoming a woodworker without any expectation! Anyway, bless you for what you do and how you do it, and best regards from France.

Richard

Answer:

Thank you for asking this question, Richard, it seems we have both done things in reverse of each other.

In many ways I saw writing the book as a bridge between generations where a period of absence left an unplanned void left by sociopolitical and economic shifts in our western culture. We all know that nature does indeed abhor a vacuum and with the loss of experienced craftsmen put out to grass with early retirement packages resulting from redundancies in craft trades like mine, and then too most if not all other crafts too, there remained only the colleges to train anyone wanting to take up a true craft apprenticeship. I think it's common knowledge that college teachers and instructors have only moderate experience in the 'outside' world of commerce and craft training and teach mostly from a textbook background. They don't cover the core issues from a real working knowledge any more so we felt that the book could provide what may otherwise get lost. We didn't want a general nod to the traditional values of hand work to replace what we once had. Hence the void when it comes to filing saw teeth, turning scraper burrs. Most colleges no matter the continent do not teach even the fundamental levels of what we cover in the book and DVDs. So, here we see void #1 filler substituting for someone working under a craftsman or woman.

With primary information about hand tools now coming via tool catalogue companies online we began to see void #2 filler kick in. Salesmen and women are generally seen all the more as experienced staff when in reality the expertise they have is usually more informational surrounding sales than that of the crafting artisan. I am often asked by an unsuspecting sales person of around 20 if I need foam brushes and wood filler when being prompted by what pops up on the screen at the checkout. Magazine editors and some contributors take up the new slack with yet another agenda to market brand names advertising with them so void #3 filler takes up the slack.

With mass information traversing the globe by gigabytes per second per second, the real working knowledge in essential terms about hand tools becomes all too often buried in both mass information and misinformation too. The excesses of modernity then becomes hidden if you will with the proverbial needle in the haystack and then, ultimately, forgotten. Such misrepresenting of information eventually becomes culturally expected and worse still accepted too. It then becomes cloaked and without reinforcement from practicing artisans in the lineage that once protected the core essentials, links in the chain become broken and we lose what was once common.

In bringing this book to market I tried to recall everything that was passed to me from generations of craftsmen and then added my own discoveries about tools that I had found could be adapted or adopted beyond their original intended use or function. Cutting to the chase didn't make me the most popular kid on the block, but we survived the scuffles and gradually saw light at the end of the tunnel. People started experimenting with the suggestions we made and the book is my way of saying let's not forget past inventors like Leonard Bailey who designed 90% of all the metal planes we know and love as the the Bailey- and Bed-Rock-pattern planes. The reason Sheffield companies buy up available names from the Sheffield stables long gone is not because they invented anything but because their own names have no value.

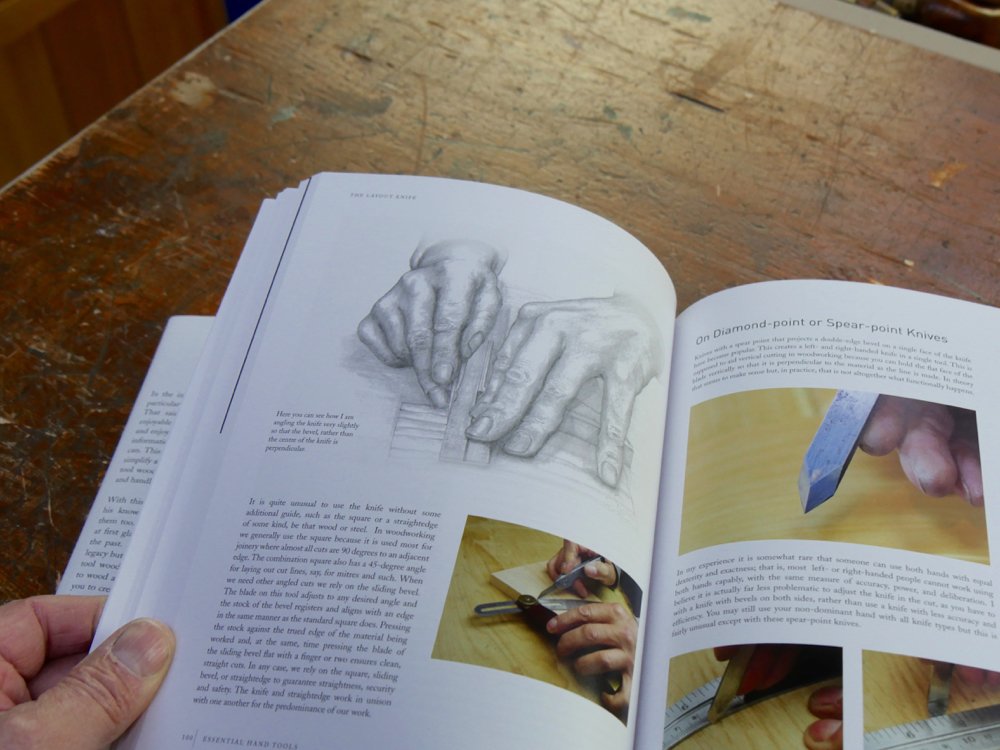

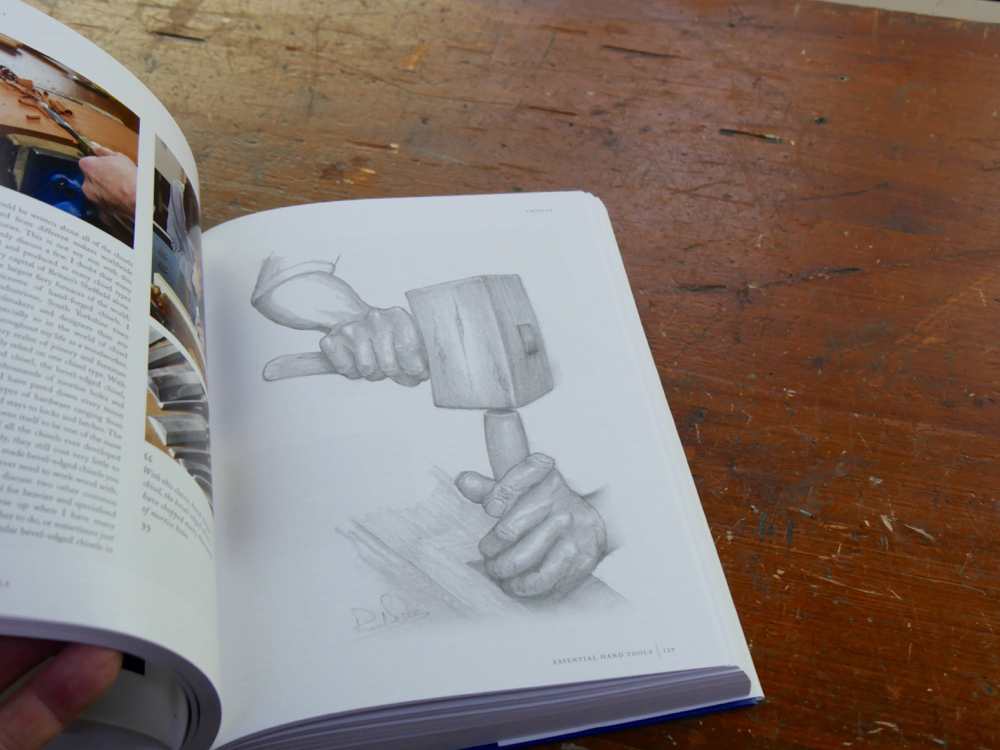

I wrote the book to show that with under about 30 hand tools, which includes the sharpening equipment to maintain them too, you can make almost anything from wood. The tools are generally available as new or secondhand tools but what I wanted to show was that even new tools must be sharpened eventually and they can and do go out of that perfect working condition remarkably quickly. This then necessitates a working knowledge for the everyday, minute-by-minute adjustments you need in the working of them. The book then covers the whole of this but then the DVDs kick in to show hidden information that in the pre-film or pre-digital era would be difficult to express in words. For instance, sharpening gouges using a figure of eight action was very conventional and so too rolling the gouge to gain the edges you need. With video this simplifies the issues remarkably as does saw sharpening where we cover both ripcut and crosscut sharpening and then show visually how we adjust the file to develop the rake to the teeth.

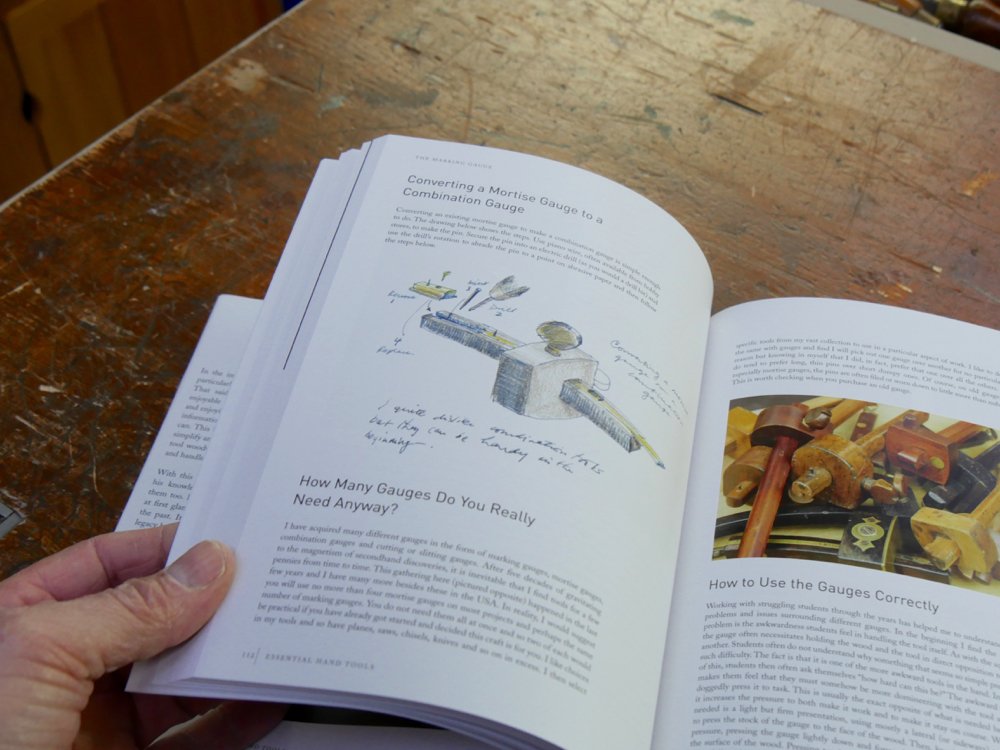

Lastly, I do have feelings about my work and the possible closing years as and craftsman. Books may well be on the decline but I still feel that books are the very best of tangible records to keep information alive. The decline has happened for many reasons and yet I too find myself delving into the archives to look for old manuscripts for information and explanations. I find myself searching for answers, yes, but then I like to convey my personal feelings from knowing the tools I work with from my long exposure to them. Philosophy is often edited out for clarity, brevity and simplicity. Many such thoughts were left in these pages as were drawings from my journals and sketchbooks that so personalised the work and put my thumbprint as my signature in place.

Comments ()