Setting the traditional wooden spokeshave

....continuing on from the last blog I wrote.

These spokeshaves are not complicated or difficult to set provided everything is in fairly good shape. Complications come when the tangs are rusted into their sockets which is not at all unusual, or the forepart of the spokeshave is so worn away that there is massive gaping hole above the cutting edge. There are different reasons one not working well and being difficult to set and use. Sometimes the tangs are too loose and won’t hold their position in the holes. This often happens when they have been rusted into the holes and separating the tangs from the spokeshave pulls away rotted or damaged wood. For now we must assume all is well, the wood is good and the tangs are capable of tightening and turning loose.

The four-sided tangs are indeed a friction fit relying on a compression fit as well as the slope of the four sides inside the four-sided hole. Amazingly this works and works well. You would think the compressed walls wood give out eventually and of course sometimes they do, but I have bought enough and used enough to say it’s worth the rick in buying at least one of these as a user. They are wonderful tools and well worth having in your user selection of tools. If on the other hand you want to own something with a more guaranteed outcome for a user and you like the idea of making your own then plum for the Veritas kit. I have run courses in making these and they are indeed all you want from a blade-soled spokeshave. They work the same way as the conventional ones and they are quickly and easily adjusted without any fuss of needing added tools like screwdrivers and allen wrenches to adjust the mechanisms for depth of cut. I have owned three or four of these myself for about a decade or more now and find them about as good as it gets.

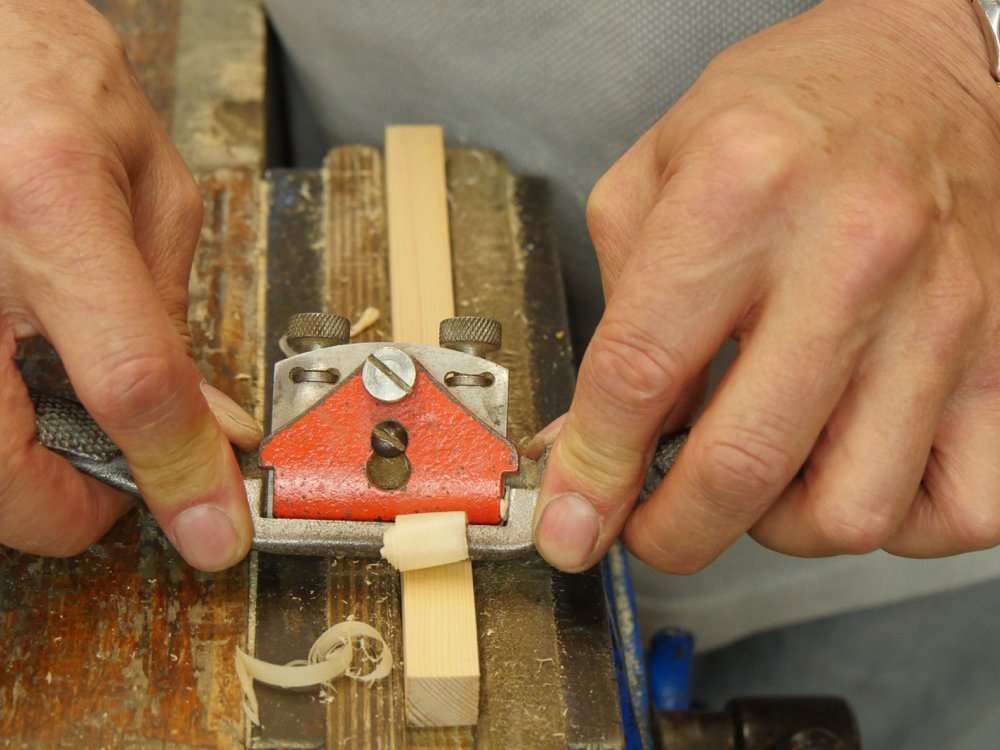

Once your spokeshave is sharpened as per the last blog, tap in the blade until the tangs are fully seated and working equally on each tang side

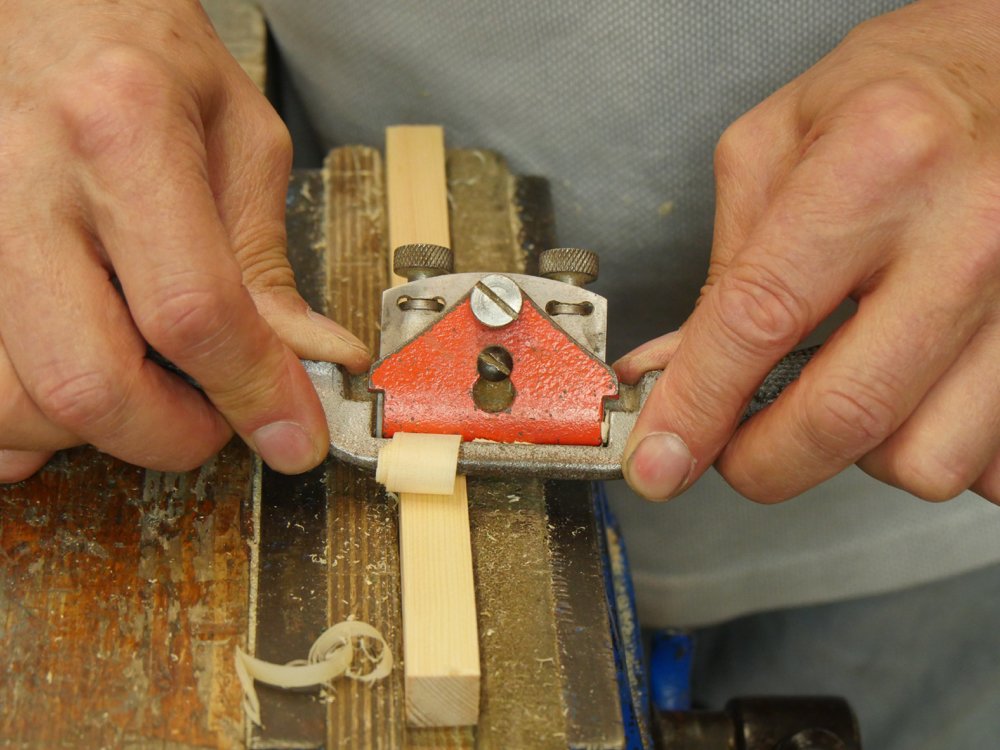

Using a thin strip of wood held in the vise, offer the spokeshave to the wood first offering one side of the spokeshave blade to the wood and then the other. There should not but could be a saving emerge depending on the condition of the spokeshave and other things too. Makers matched their blades to individual spokeshave at the point of installing the blade and making the spokeshave, a lifetime marriage of one part to the other with not intentions of the two interchanging elsewhere ever. Of course we can always make an adjustment of a blade snaps and we find another provided we heat the tangs to bend them and reshape them or make a new spokeshave and install an existing blade fitted for that purpose. Lets assume all is good and no or just a small shaving emerges somewhere. Its at this point you have a decision to make. Depending on the nature of the work you can set the cutting edge parallel as you would any plane, which is what a spokeshave is really, or you can offset one side so that it takes a thicker more aggressive shaving from one side of the throat and a thin or zero shaving from the other side. This gives us an infinitely variable ability to move from left to right to take thick shaving for roughing out and then a refining shaving for finishing. For chair makers this was a standard procedure being as they were mostly making spindles and legs, rungs and so on. It was quick and effective to work economically by hand this way. In fact, we often do this with spokeshaves that have adjusters too because it is so effective.

With a zero cut setting or thin shavings coming from the throat it’s now merely a question of tapping the tangs with a steel hammer and testing on the thin strip of wood to test the thickness you want. Tap the tangs with the spokeshave held in front of you lightly. A light tap will give you a thin shaving adjustment. Tap twice for doubling the thickness and so on. If you tap too much and the shaving’s too thick tap the underside of the blade to correct it. The offset idea of the uneven setting os mostly for rounding work, which is why the old chair makers used them that way, but at the bench we use to that way for rounding over work to create roundovers we call bull noses. This happens on say window sills and stair treads and especially where the the stair tread is round at the bottom of the staircase, places like that. We use it for kitchen ware like spoons, spatulas and cutting boards too. For cabinet and furniture work, joinery work and so on, we often want the spokeshave set parallel as we would any plane. This gives us the control we need. Always remember that the work of rustic woodworking commonly known today as green woodworking was just a segment of woodworking carried out in woodland regions by a group of chair part makers known in England as chair bodgers. This was in an era now long past and though a substantial part of the woodworking industry of the period in terms of overall furniture making this played only the smallest part and not the whole, not the predominant user at all. The bodger of course was highly skilled using the lathe and so should be if most of your work is replication of the same or similar components by the thousands from dawn until dusk. These men were hard workers working in a competitive era and the use of the lathe gave them the speed they needed. Ultimately of course mechanical replication won to and gave the companies the control they wanted together with the speed too. The electric machines ultimately rendered them redundant. Turned parts from dry wood and cutter heads that made their parts in seconds with a pristine finish meant hand work was gone. The spokeshave filled in the gap for some work that could not be worked on the lathe however. Crinoline stretchers and bow backs, long thin spindles and so on defied the lathe and had to be cut and shaped with the spokeshave and finished ff with chair devils. The spokeshave was indeed a fully refined tool used by every segment of the woodworking world of course and these trades included barrel makers and pattern makers, cabinet makers, joiners and carpenters of every type including shipwrights, and two dozen more trades.

So we see that the traditional spokeshave still has a home in our user tools and of course we often adjust the 151’s with their adjusters the same way because of practicalities. I learned this when I was 15 and the men I worked with introduced me to their wooden spokeshaves.

Comments ()