Understanding the frog in your throat—Part II

Looking at the two frog types—the art and sole of the plane

Now that we may have established that adjustable throats are perhaps more a less necessary feature rather than a necessity, let’s take a more educated look at the two throat types to consider how we evaluate their pros and cons.

Using the two plane types, regardless of maker, you must first ask yourself how the contrasts between the two plane types has been framed over recent decades. Remember that craftsmen in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s rejected the Bed Rock almost out of hand, but they did gradually accept the Bailey-pattern model as a viable replacement for their wooden counterparts. The Bailey-pattern predates the Bed Rock by a couple of decades of course, but the big question for me still remains as a capital Why?

In my view it wasn't that the Bailey-pattern actually failed in any way in creating an adjustable throat to a plane and yet perhaps there was something in the naming of the alternative offering of what became known as the 'Bed Rock' plane that suggests the name went to bedrock in resolving a perceived problem. Personally I think this comes back to the issue of framing the issue. Having any frog, no matter the plane type or maker, builds something into the chain of command and so any such link more introduces a problem rather than resolves it. That said, it wasn't really a problem not having any such adjustment for prior centuries of hand work before its invention, but once invented, no one wanted not to have some kind of throat closing capability. To me this starts to feel a bit like the emperor's clothes, but non the less people did seem to want the ability to open and close the throat. It doesn't seem to me back then that the frog type was really an issue at all either. I know that the Bed Rock only became more popular when it was revived in the latter quarter of the 1900's when woodworkers were looking for something more refined and of better quality. I think Lie Nielsen succeeded in producing one of the finest planes available and provided an alternative quality that countered the mediocrity resulting from the complacency in western tool making by the big entities of the era. I would that a tool maker would revive the lightweight # 4 to the same standard size but with the added quality. A plane like that hitting the market at around £125 would be wonderful for those looking for a topnotch new plane. I have a few features of my own that I would like to add to the design too.

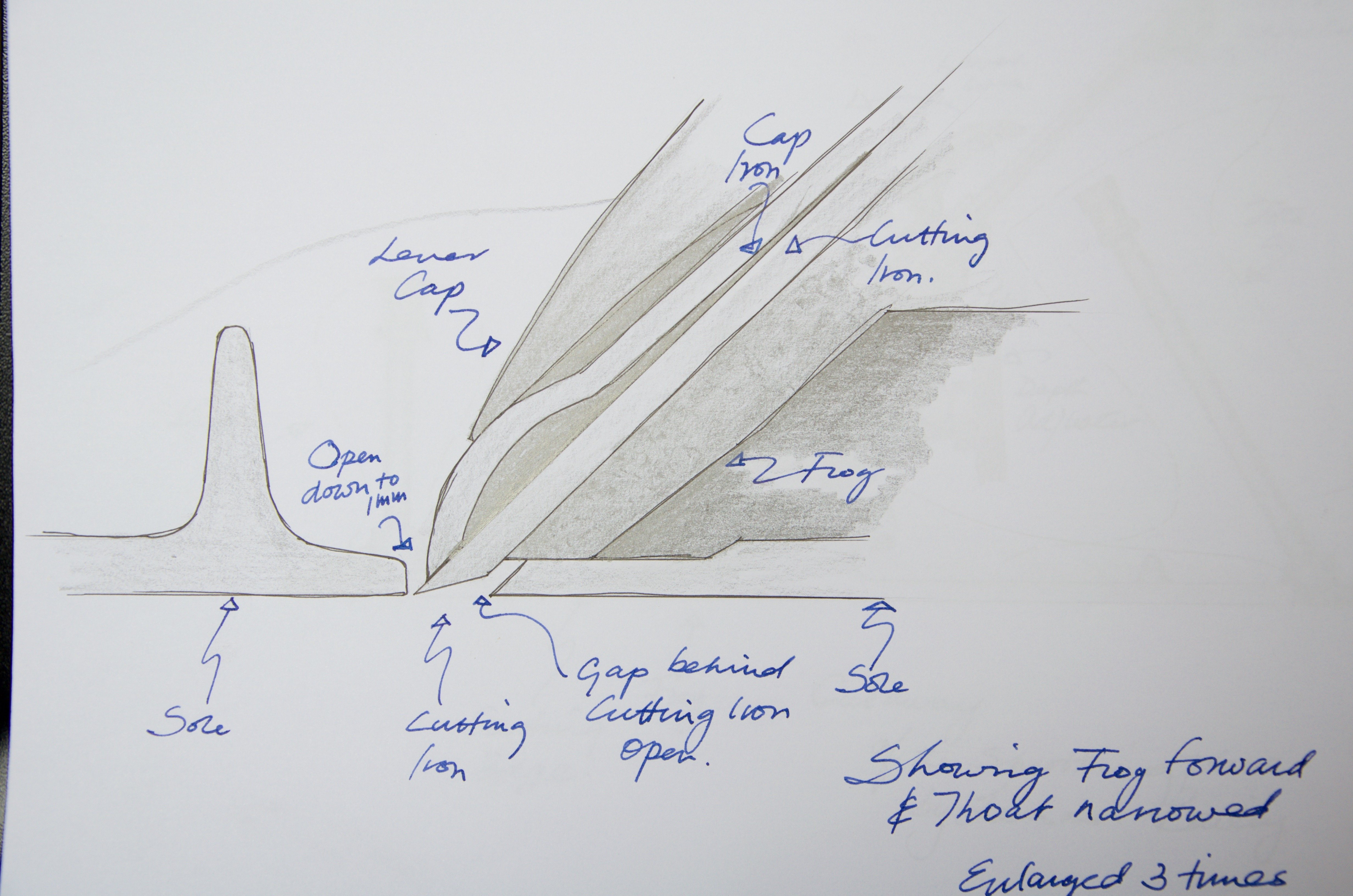

If we examine the Leonard Bailey-pattern plane we see two set screws that lock the frog to the main body of the plane quite solidly. An adjustment screw sits directly below the adjustment wheel at the rear aspect of the frog that facilitates changes to the throat opening (shown below). Notice in the drawing that the frog rests on two levels, an upper level to the top and rear of the frog rise, and then to the lower edge at the forepart of the frog and directly onto the sole of the plane itself. This forepart of the frog divides into a spit section so the frog actually sits on three points, two at the front and one at the rear.

Because the Bailey frog basically sits on two flat plateaued levels, the frog actually moves perfectly parallel to the sole of the plane. This is a definite advantage to the plane and frog type because moving the frog back and forth does not generally affect the depth of cut.

The Bed Rock plane adjustment relies on two opposite or counterpoised inclines; opposing wedges that adjust the frog in relation to the throat opening by the one block of metal sliding up and down according to the desired opening size. Herein then lies the first chief difference between the Bailey-pattern frog and the Bed Rock frog. Not only does the Bed Rock frog move backwards and forwards to alter the distance establishing the throat opening according to need, but, because it does slide up and down to make such adjustments, it also changes the depth of cut dramatically and in an uncontrolled way too. That being so, you must always remember to withdraw the cutting iron back up the incline before presenting it to the work otherwise you will find the plane can gouge and tear the surface of the wood.

What may not be noticed or generally addressed anywhere is that the fore edge of the frog itself can protrude through the throat ahead of the cutting edge and the frog can thereby damage the work. This is not generally a problem because when the cutting iron assembly is housed on the frog it disallows moving the frog too far down. On some imported plane models it is necessary to file the fore-edge part of the frog back a little.

The frog adjustment on the Bailey-pattern plane frog relies on a centre screw thread to move the frog backwards and forwards. This threaded mechanism is actually tapped into the sole and not the frog but an adjustment screw-feed transfers feed to a ‘U’ shaped yoke that facilitates direct adjustment to the frog. The screw-feed adjuster has a channel that generally prevents the frog from moving backwards and forwards once the screw-feed screw is distance set to throat size. Without a screwdriver turning this screw-feed screw the frog is pretty much distance set and so prevented from moving backwards or forwards. Two setscrews inside the frog itself actually serve to lock down the frog immovably to the sole. If these two setscrews are indeed locked they disallow any movement in any direction and so we see that these two setscrews are designed maintain frog alignment square to the throat and the long axis of the plane length.

No, you do not have to dismantle the cutting iron assembly of a Bailey-pattern plane

This is what everyone says you must do, but you don’t need to at all usually. I was taught a different method fifty years ago and I have used it throughout those fifty years without flaw or failure. Try it for yourself and see how you feel. remember though, that you may find you won't change your frog setting but every few years. It may not be an issue at all.

In my work I set the frog alignment and distance in relation to the fore part of the sole as needed. Usually in its back position. Regardless of the frog position the setscrews lock down the frog to the sole, but here’s the difference between me and modern-day woodworkers. I tighten down the screws fully and then back turn the setscrews a bare fraction of a turn; perhaps an eight of a turn, no more. This allows me to readily change the feed screw backwards and forwards at will without further touching the two setscrews. In turn this means that I can fully adjust the frog without removing any of the cutting iron assembly or loosening the lever cap. So what everyone should hear here is that you do not need to remove anything to adjust the frog of a Bailey-pattern plane. This then is often the very thing anyone selling Bed Rock pattern planes states makes the difference advantaging the Bed Rock plane over the Bailey-pattern plane.

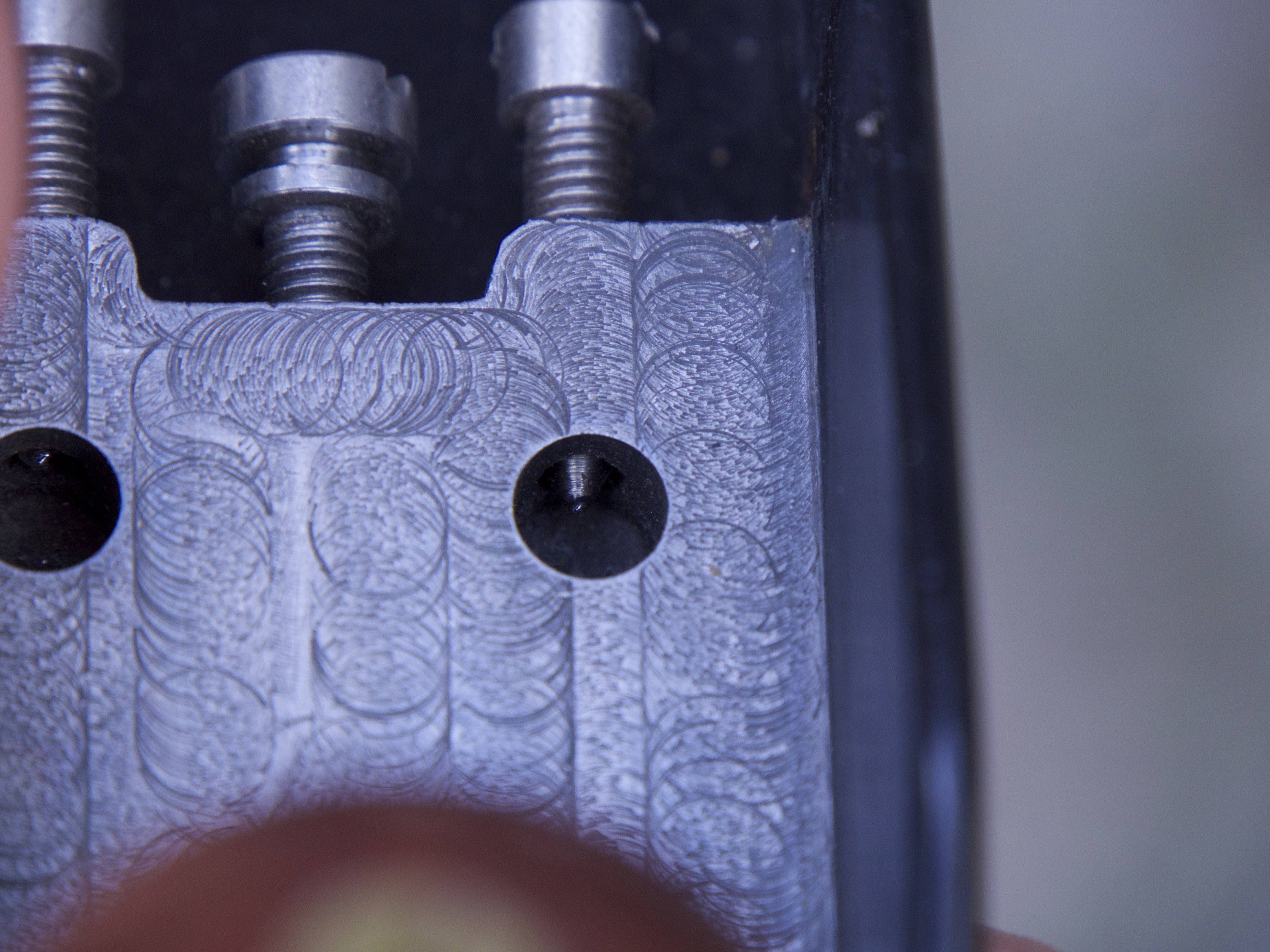

Now for the Bed Rock pattern plane adjuster

The Bed Rock adjustment is more complex in engineering and yet simple in functionality. Three screw threads at three points of contact lock the frog to the inclined slope. This three-point contact allows the frog to be adjusted forwards and backwards and up and down synonymously, even though the up and down movement disadvantages the functionality of the adjustment. Two conically pointed screws locate into two steel pins that pass through the frog into two holes in the main body of the sole, perpendicular to the flat recesses in the inside of the inclined frog and also to the incline of the sole itself. A ‘U’ shaped yoke, the same as the one on the Bailey-pattern plane frog adjustment, serves to then move the frog as a feed screw and so the actual adjustment method is identical to the Bailey-pattern frog adjuster. Here, then, the main difference in locking the two component parts down are the twin pins. It’s very solid. Whether this validly betters the plane over the Bailey-pattern is debatable for me.

Concluding

Beyond this then I feel the two planes need periodic frog adjustment about every year or two in general depending on the nature of some of your work. If you are a fine woodworker thinning fine parts or refining fine surfaces and feel the need for a closed throat most of the time then both planes do give you the same optional adjustability.

I have considered this subject carefully because it’s important to me and to others. I own or have owned every type of Bailey-pattern and Bed Rock-pattern plane for over 50 years. Being on an inclined plane alters the set of the iron markedly using any of the Bed Rock planes regardless of the maker and so needs immediate adjustment beyond altering the frog to compensate for the additional depth of cut. This is not particularly a big thing but it's also rarely ever mentioned because the benefit of not having to remove the iron is often espoused as a virtue yet you cannot use the plane as a result of the benefit straightway because the plane iron is altered every time you make the adjustment. That being so, the benefit of being able to adjust the plane externally is disadvantaged by the need to reset the plane every time the frog is adjusted. If, as is a fact, you do not need to remove the cutting iron assembly of the Bailey pattern plane, then the Bailey-pattern plane remains a coequal contender and might even be considered the more general practical all rounder.

Remember though, I have woven throughout this article the reconsideration of whether throat openings and the ability to adjust them is as critical as we have been led to believe in the recent decades or, for most woodworking, are they merely just another add on. I know I consider myself a fine woodworker and and fine furniture maker specialising in hand work. I generally don't adjust the frog in my throat.

Comments ()