Questioning the Cross-grain Rim On Toolboxes

There are concerns about the type of lid fixing to the toolboxes we made where the lid is skirted crosswise to the main long axis of the grain of the lid with a lip covering the end grain at each end of the lid in the traditional manner. I understand the comments and the concerns, but then again, it’s not so much perhaps an exam piece but a near replication of something that has been common practice for centuries and so there I almost rest my case, well, initially at least, and with no pun intended.

On all of my toolboxes and tool chests I use frame-and-panel, a method also very traditional, but of course it would be pointless to do a replication if you change everything because a better way was devised. The reality here is that no modern woodworker came up with a better way beyond reconstituting the materials common to the craft like a Pringle chip so that it stacks up in the box as sheet goods do and use MDF to get around the issues of expansion and contraction. Of course the life span of most MDF goods are not what we were promised when magazines in the late 70’s in the US were saying MDF was the new miracle material that could be a great substitute for wood and one that could be routed, sanded and stained and would change our need and use of wood. MDF was never a real alternative in furniture making for real woodworking but machine-only woodworking mostly; that is except for those building in ways to limit life expectancy and create fashionable and mostly but not always disposable product.

Putting ourselves in the place of men building boxes like these shown above, from the centuries before, helps us to place ourselves in true realms of realness when working people knew no such thing as the luxury of leisure time, disposability and short shelf-life furniture pieces. They didn't buy wood as we would from Home Depot or B&Q in S4S sections pre planed and such. Boxes like these had no counterpart in the form of plastic alternatives and people traveled the globe, boxes in tow, stowing their chattels in cases just like these to contain some of their most valued possessions, not the least of which were indeed the tools of a man’s trade. For some, this traveling container was purely a transitional step to one of the colonies and a new life. When I moved to migrate to the USA I made twenty 3/4” plywood boxes glued and screwed together and skinned each side with 1/2” plywood. Strong and watertight, half of them were filled with my tools and the other half treasured family stuff. These boxes became cupboards and shelves in my shop and as far as I know are still wherever they were screwed to the walls in different workshops I left behind me as I moved on.

For others intent on protecting their tools in previous centuries it was more important to make something that was lightweight and strong and built to last. These boxes fulfilled their existence as being fit for purpose and, though perhaps in an era of unknown and uncertain futures, unable to predict what would happen, they have proven themselves worthy of total respect in the fact that we are using them now a hundred or hundreds of years later on. The boxes traveled continents and supported craftsmen through two world wars. They transported tools to and from work places and kept them safe in workshops too. No small thing and especially so when I think that I own several of them and still use them today for keeping and protecting my personal tool collections.

It’s interesting to see the responses people have had and the discussions issuing forth and yet no one actually acknowledged that hundreds of thousands of chests were built and used just like those shown here over at least four centuries. Was it that no one knew what we knew today? Not at all. Woodworkers did what was necessary. It took much more work to create the more sophisticated framed panels that also date back through at least half a millennia. This system was developed to make doors that would not shrink too much and panels that remained solid and constrained in a massive range of situations. Security was the key issue in eras when people really valued even the smallest of possessions in a none disposable or fashionable age. That meant that chests had to be durable, strong and fit for purpose at the very least.

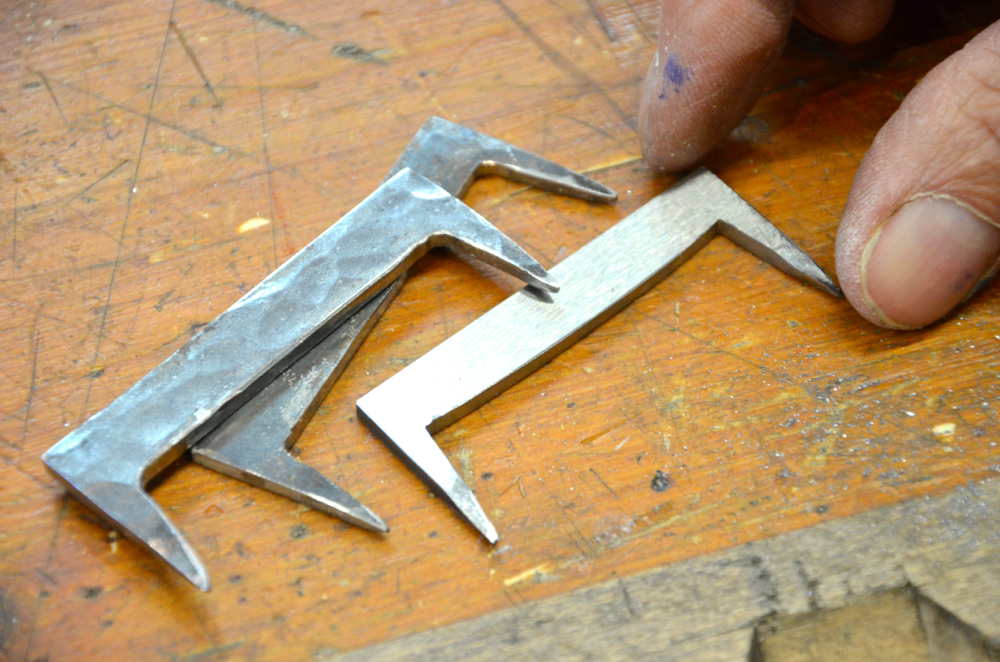

I have noticed how much more people do obsess about things like expansion and contraction. I noticed this when I wrote on spring clamping wood where some people said I had it the wrong way around and I should really not have clamped the ends with a clamp at each end but with the one clamp in the middle and a slight concave rather than a convex along the edges of the conjoined boards. In actual fact you can do it whichever way you want, slight convex or concave. Back in history people used the nail dogs I showed extensively, which defies everything the naysayers said. Now then, that said, there are considerations in that people today live in an era of total air-conditioned immersion, where everything is conditioned to a certain dryness and temperature. The ends of boards supposedly dry out faster than say the mid section of a tabletop or, as in this case, a chest top. That’s not so interactively concerning when you nail on the end piece though over longterm exchanges of moisture can become an issue and might in some cases become problematic. But the problems can be adverse either way. I think too that gluing and nailing can occasionally be a problem because it is very rigid and immoveable but rarely is it actually so, and especially in Britain where we have pretty regular levels of humidity. The glue does seal the end grain pretty well and prevents the ingress of moisture except in long terms of exposure or immersion. In the US there are other considerations such as the differences I found between east and west Texas, Arizona and Arkansas. It's simple enough as I said at the time. Keep the wood in the same conditions it will be living in if possible, let them acclimate, and then get on with the build. Your box will most likely be fine. Here and in other situations, people who believe this will usually never risk making a toolbox like this, even though it's more likely to work out than not. It’s a shame really because the toolbox may never do what they’re fearful of at all.

Comments ()