Sharpening Is Mostly An Abrasive Issue

The title of this post seems almost a contradiction of terms. Sharpness and abrasion; how does that work?

Sharpening most cutting tools and cutting blade edges is not particularly complex but it will take practice to establish patterns of guaranteed success for the freehand sharpening methods that make you expertly fast and effective. Oftentimes we start out sharpening using a honing guide and that does work to get to the cutting edge we need. Eventually though, you will want more, you will want to get the edge faster so you can get on with the real work you love to do. As I said, sharpening cutting tools and cutting blades is not really complex, but it can be made more difficult when you move into harder steel types like high-speed steel and hard steel alloys or cutting edges made with superimposed tips and edges like tungsten carbide. That's when you must cross a line to use more industrial methods. Then commercial abrasives and diamond cutters combine with power and speed and take over to project you into the less pleasant world of industrial abrading and metal cutting. So, it's here that I've decided to take some time out, to present thoughts and feelings as concisely as possible. Opinion is one thing and there's always lots of that, experience another, so let's see what happens in the reality of daily, at-the-bench working.

Experiencing makes a difference

What I’ve seen over my five decades of daily sharpening and of course teaching others to sharpen by the thousands is mostly confusion. Yes, there's lots of head knowledge, but that seems not to have really helped because it's relational knowledge that dispels confusion. What I have experienced as normal is just how confused people seem to be when it comes to what was once simply a simple sharpening process. My quest then is to see if we shouldn’t look at what it takes to get to the cutting edge and circumvent the confusion by myth-busting some of the mystery. In the age of information overload I found it quite challenging penetrating the excesses of information purporting to be technical advice. What the information doesn't give you is experiencing the stones and the abrasives and the compounds, so what I want to try to do is use 50 years of sharpening at the bench to bridge the gap and give advice I hope will make sense. I think I can cut to the quick and we can return to the simplicity we all need.

Information overload

I'm sure I'll be ranked amongst the information overloaders by the time this post is read, sorry for that, but it has to be said. A student this week asked me about sharpening equipment and I pulled out a popular catalog of tools to help her understand which systems or stones would work best for her. To compare what was offered and guide her into making educated decisions. Try as I might, here was no way that that was even possible.

The lady's budget was around £30 max. Thumbing through the pages it didn't take long to see that £30 doesn’t go very far if you read what the salespeople and manufacturers have to say on the matter. Fact was, if you listened to them at all, you’d spend hundreds more than you really need to and end up with many times more than you need into the bargain. A little more thumbing through the pages and she stopped me and asked, "How much of this do I need? With so many pages on just sharpening she asked how would it ever be possible to understand so complex an issue with so much equipment necessary to sharpen a chisel and a plane. It was at this point that I stopped her and counted the 21 packed pages and I realised the confusion was the array of unnecessary stuff available and were I a beginner I too would be confused.

Are Machines Necessary?

The quick answer is, generally, no, but you might want access to one for heavier grinding work to restore badly ground, damaged or flawed edges from time to time. They are useful for that. Many things have changed the face of woodworking not the least of which is the industrialising of craft aspects we once took for granted to be hand work. In sharpening today most people use a mechanical system of grinding, be that a simpler electronic grinding wheel with two different grit-grade wheels, a horizontal grinder flushed continuously with water cooling, vertical and horizontal grinders with abrasive belts and discs of some kind and so on and so on. This of course opened a massive sphere of sales for sellers to sell the wares of the industrial abrasive giants like Norton and 3M and so when you add into this equation different stone types and sizes, different grits of every level and belts and compounds graded out too you can soon end up considering a hundred products those new to woodworking might think to be necessary. I think this is a good point to say that in general, when you have chisels and cutting edges in general good condition, you don't need any kind of mechanical machine grinding to sharpen your edge tools.

Catalogs compete with the old brand names by supplying knockoffs

What has happened with machine grinding abrasives has also happened on other fronts too. Now we have natural water stones, diamond stones, a monstrous range of man-made stones in diversely different grits and particulate types too numerous to mention. Over and above that you now have everything doubled up. When Asia and the west opened up the interexchange trade routes to intercontinental and especially Asian factories, new trend began with the replication of established lines. In a few short years knock-off brands copying the originals was normalised with and without licenses. The quest to satisfy what was then Western consumerism at compelling competitive pricing,open new the floodgates all the wider and catalog companies across the globe began to swell their offerings. Even the reputable companies sold out the honour of their forebears to take advantage of the cheaper labourers. Spear and Jackson, Woodcraft, Rockler and Irwin. Machine makers too have goods and parts made in the anonymous world of "somewhere abroad". The Brits and Americans and some EU countries became exceptionally good at copycatting ideas and having their stuff replicated somewhere in the expansed regions of Asia at half the price and less. That meant they could run both levels side by side to offer some price break to their customers but mostly to increase their own profits and compete. Everything made that at one time only came from what we might describe as say a reputable domestic maker suddenly became available from other ’alternative’ suppliers, but, now, under the catalog companies own brand names.

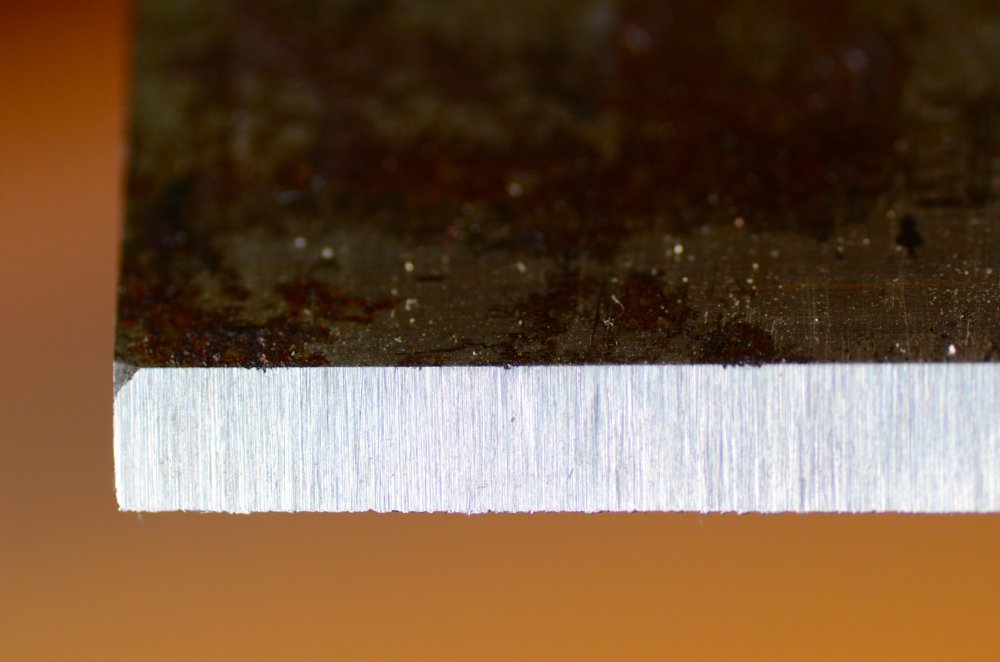

Hard grits, soft grits, hard steels and super hard steels

The reality is that different abrasives cut steels at different rates and speeds. The variance depends on the hardness of the steel and the abrading qualities of the different abrasives. Picking the abrading method introduces additional confusion into the arena of sharpening. Up until about four decades ago I recall that sharpening was really quite simple. Craftsmen always generally used freehand sharpening methods and most, not all, amateurs preferred to use risk-free honing guides as a sort of training aid until they gained confidence and competency free handing. Using Japanese stones, mostly natural stones back then, gained rapid popularity, mostly because western woodworkers were looking for answers. For some unknown reason simple sharpening methods were buried somewhere. It was as if the art of sharpening, no matter where, had suddenly become lost; forgotten. It was about that time that Japanese water stones and abrasive paper methods of sharpening (known for some reason as the scary-sharp method) became popularised. Both methods were seen somehow as revolutionary systems; an answer to all sharpening problems. On the one hand you had friable stones that cut steel fast but surface-fractured rapidly. This then led to severely hollowed out stones that supposedly needed permanent flattening and in some measure that might be true. We'll look at that soon. On the other hand abrasive surfaces such as abrasive papers and films tore easily and were short lived surfaces needing constant replacement. This proves a very expensive system for permanent or longterm sharpening. Before this point most workmen used oil-filled man-made or natural sharpening stones throughout Europe and of course North America. Why people became disgruntled with them I don’t really know. These abrasive stones all worked and worked well and, actually, they still do. If you don’t have much money you can get a very good cutting edge with a Norton combination stone and a leather strop. Most working men I have ever known would be content that these edges are good enough for creating good work.

So what am I saying?

Well, I’m saying that there are different camps. Some people like to spend an hour or two sharpening an edge to take pristine shavings that ripple from the throat of a plane and mesmerise the plane user. They want the plane finely adjusted and nothing more than shaving the edge of a piece of wood. To them it’s therapeutic and relaxing. Nothing at all wrong with that. Then there are those who love planing their wood as they work and create beyond or beneath the shaving. They perfect the wood and the shaving because they are interrelated for joinery, for panel making and for levelling and trimming and such.

Honing guides

The fact that I never saw a master woodworking craftsman use a honing guide doesn’t at all mean they never did or do. In my purview there is nothing at all wrong with that in principle at least. I use one from time to time for different reasons and especially when experimenting for the research work I engage in. However, for me, not using a fixed angle honing guide gives me much greater speed, economy of movement and time and thereby efficiency. Equally important is I find it too restrictive in terms of the motion and movement I feel using a fixed angle guide. Now that's in my general day to day work. As I said, honing guides do have their place. You see it’s too mechanical, yes, but then it also prevents me from honing either to task or for a particular preference I have that gives me the total versatility I enjoy and get from free-hand sharpening. Not relying on the honing guides does in some ways simplify the task as long as you see that it also demands the early development of skill. The problem usually is people don’t feel uncomfortable with it at least at first and therefore they often reach for the honing guide first. What’s my thought on this? Well, I never rode a bike with training wheels on that I can recall, and of course I came off from time to time in the early stages of learning, but once I mastered the balancing aspect it took I was very free. Knowing such freedom gave me the determination never to return to the training wheels. My recommendation is that you might want to buy one of the less expensive guides like the one and only one we use here at the school. It’s quick and easy enough to set up, reliable to use and lifelong. It can also be had for under about £10. I, as an apprentice, went straight to freehand sharpening at 15 and stayed with it for 50 years. It took me a few hours max over a week or so and I had it for life.

I hope that the next post on these issues will be more interesting and enlightening.

Comments ()