More on Making - Design Concepts

I think that sometimes I have been grateful for machines and I realise their real value when woods have difficult grain. I remember one time passing a most beautiful treasure of mesquite burl into my planer for a second pass of 1/64th. Not a heavy cut at all. The first pass had worked fine and I was passing it through oriented the same way as previously. The piece entered fine and then suddenly exploded every bit of it somewhere into the cutterhead. Nothing came out the other side and 16" by 5” wide of 1/2” mesquite burl that should have made a perfectly book matched lid was obliterated. That’s not so rare an occurrence as it might seem and that’s why many users of thinner stock use planes and scrapers rather then machine planers to thickness their stock down to final sizing. I know that many guitar makers use thickness sanders to gain the thickness to exactness but I also know that Marty Macica resolves his work as I do using hand methods and no sanding. This is because he feels the sanding dust fills the grain pores with dust that deadens sound. Marty is teaching a new guitar-making workshop later this year in New York and you can see him do that here.

Resuming from my blog a couple of days ago here. My mesquite pile had now ceased to lose weight. In summertime Hill Country Texas that means it’s as dry as you will get it and that’s when I like to start putting my final thoughts on paper. The most economical way to use rarer woods is to create veneers from them. Our modern take on that is of course that veneers are somehow cheating us out of the real thing and to some degree that’s quite true. IKEA and others use thin veneers to mask what’s underneath and they might tell us it’s to save the rain forests, which of course is untrue. Most modern goods with surface veneers are usually super thin. So thin in fact you can see through them to the light sub-woods underneath. What mass makers want is something that feels and looks like real wood for its warmth and appearance and at the same time controllability to pass it through machines for tight tolerances. Adding stain to equalize colour and tone gives them and us the illusion of real and we unwittingly buy into a built-in obsolescence product. This is less true of hand crafting artisans who want the control MDF offers, but creative ways of using veneers. Box makers often use this and I recall the most prodigious UK furniture makers SilverLining making doors for the Russian Embassy in London using MDF for some massive doors that were veneered with some very special veneering to the faces. Many top-notch makers use MDF. I chose ot to do this and find ways of veneering with solid wood as a substrate. It can be done but it takes careful consideration every time.

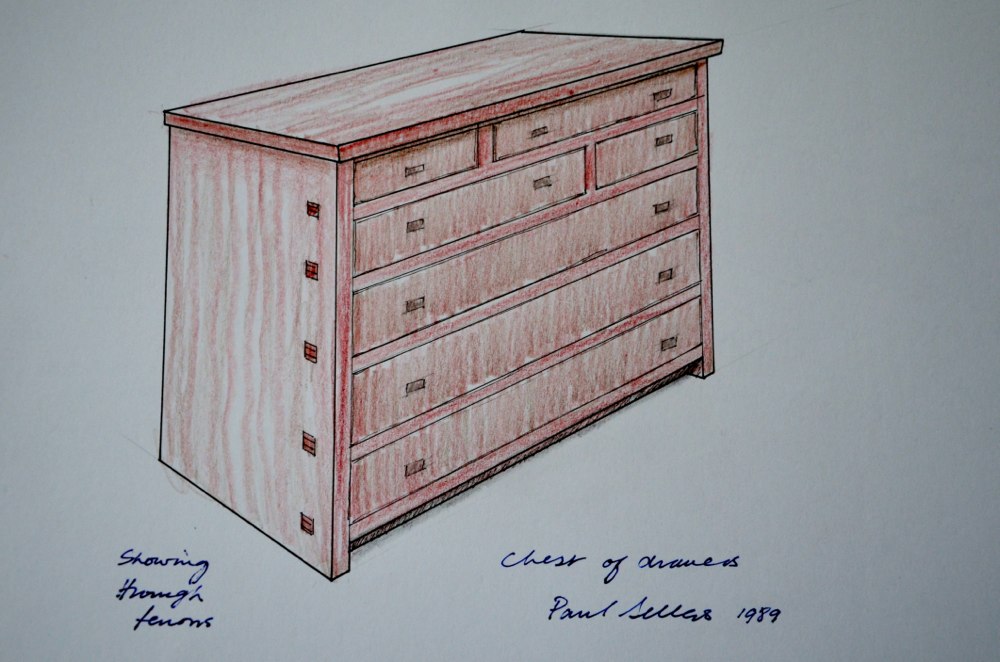

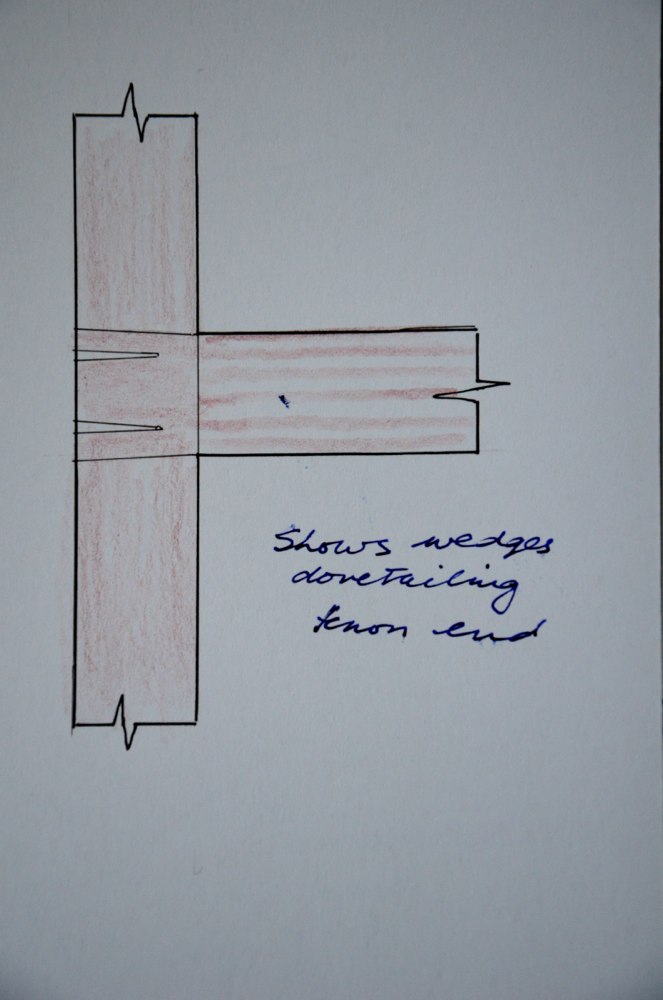

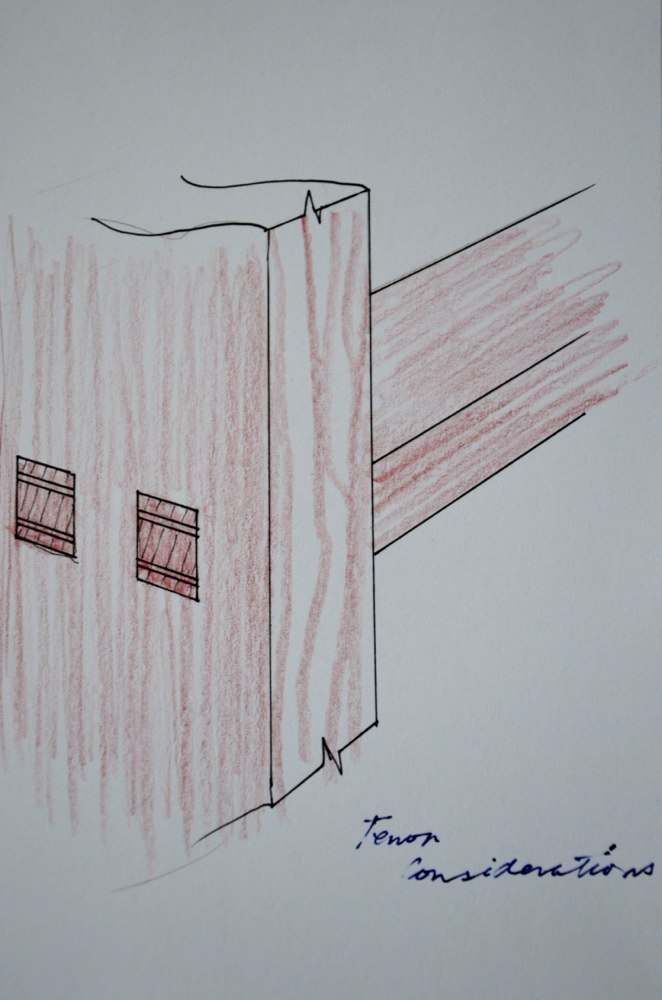

The piece I designed had many features I chose from my early signature details. The rails separating the drawers comprised hidden aspects to the internal joinery but through tenons cross-wedged on the outside. I have always liked this feature because it visibly shows the contained tenon within the mortise and the compression within that creates a lock to the dovetailed tenon.

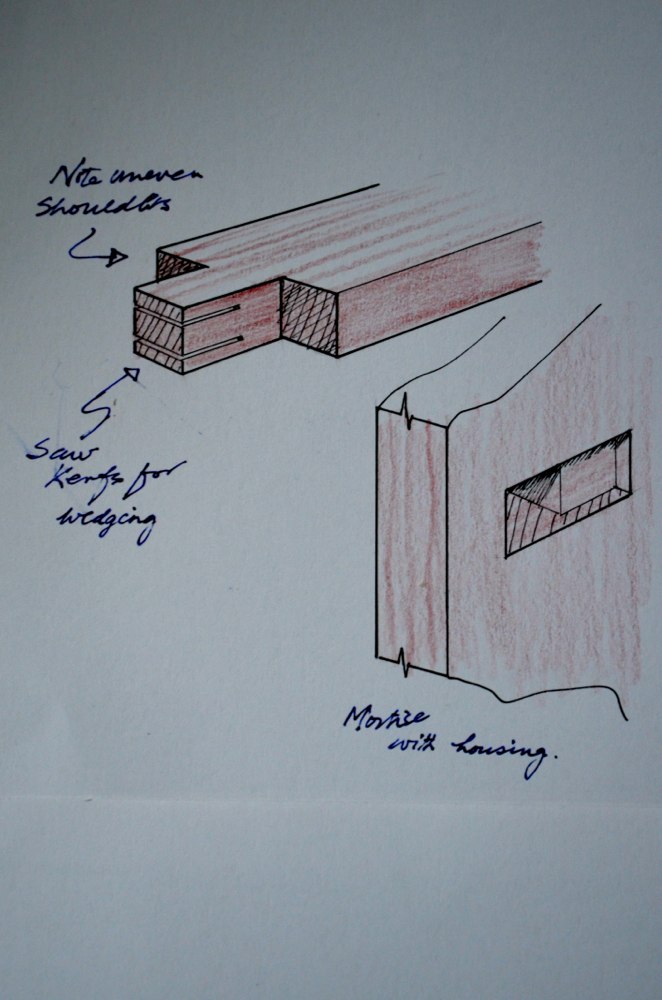

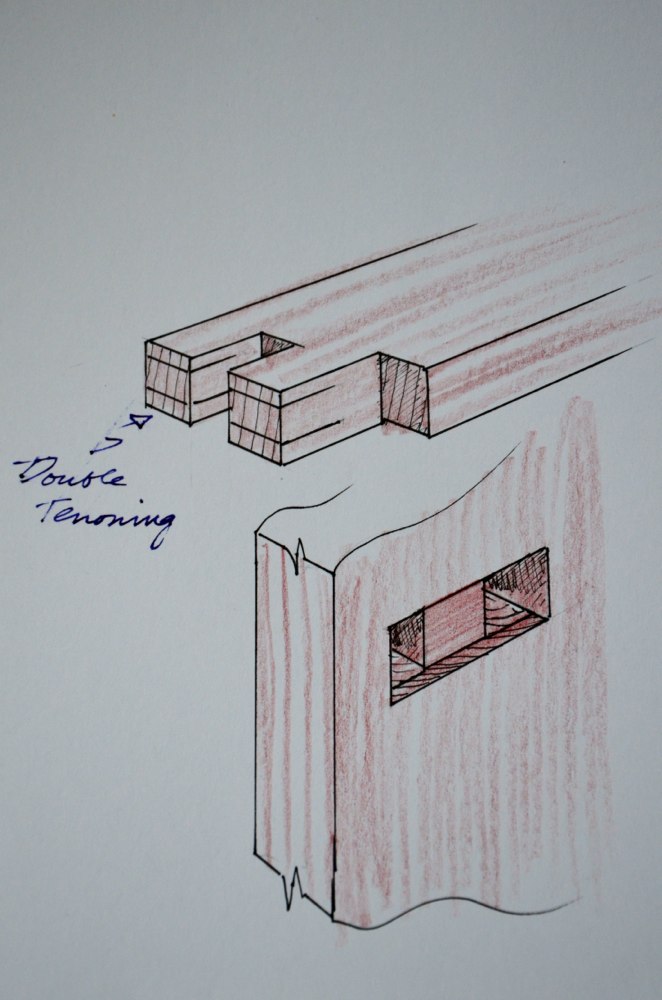

Inside the tenoned area I created a housing 3/32” deep. I wanted to support the rear of the rail. In the scheme of things all joinery necessitates one part to to be reduced in some measure to fit into another. I considered two types of mortise and tenon joints and chose one for different reasons. Here are the two options I thought to consider. The one on the left is a single through tenon. The one to the right is a twin tenon. I rejected this for this particular piece but used it in other work later. I felt that the joint with twin mortices took too much wood way. It made the joint area weaker, but I decided this based on my knowledge of mesquite and knowing it’s brittle nature. using a single tenon meant I could move the tenon further from the front edge of the side panel and increase the strength that way.

The cross wedging needs much care too because the wood either side of the wedge needs to retain continuity along the length of the rail. The wedges are not too long and must not be driven into the rail beyond the depth of the saw kerf. I start my wedge the same width as the kerf, that way the the wedge immediately parts the narrow section of the wedge to press it into the widened aspect of the mortise. I forgot to tell you that the outer aspect of the mortise to the top and bottom are widened with a sharp chisel. You can see this in the drawing. It’s always important to consider joinery in terms of its reductive parts. Widening a tenon means less wood surrounding the mortise. Reduce the size of the tenon too much and you have a weaker tendon. Reduce it too much and you destroy the efficacy of the tenon in favour of the mortise. Joinery is about finding balance and seeking harmony between two married parts. Each relies on the other, which is why when I was young the men always referred to “marrying” the various parts. It’s a reductive process you see, but one part cannot be reduced so much as to be weaker at the cost of the other.

Comments ()