Old Men, Old Planes, Old Ways Now Gone - The Origin of Scrub Planes

This Blog Post is About Scrub Planes.

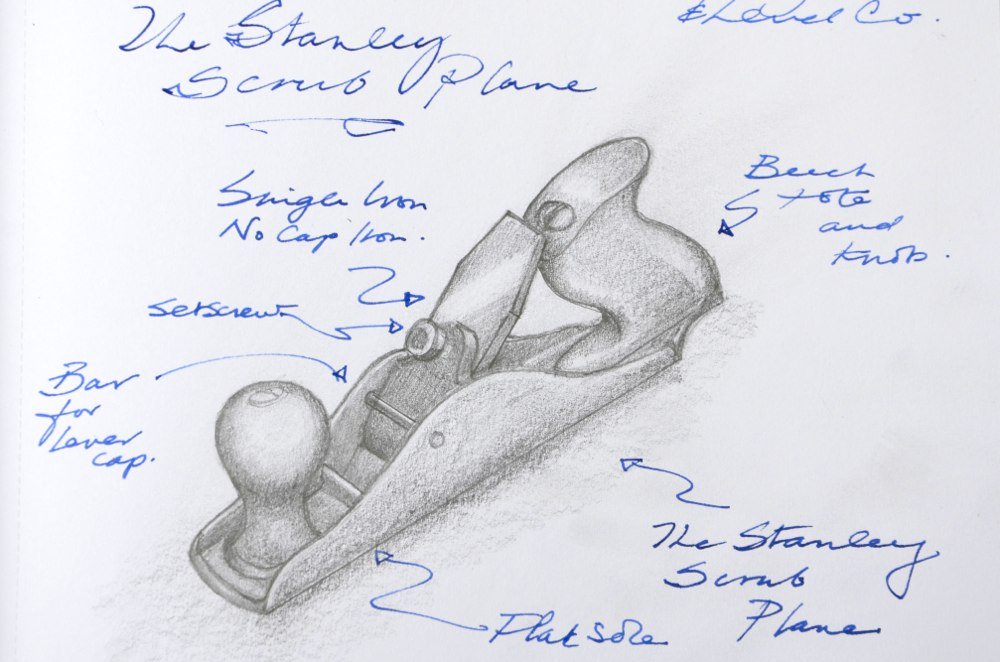

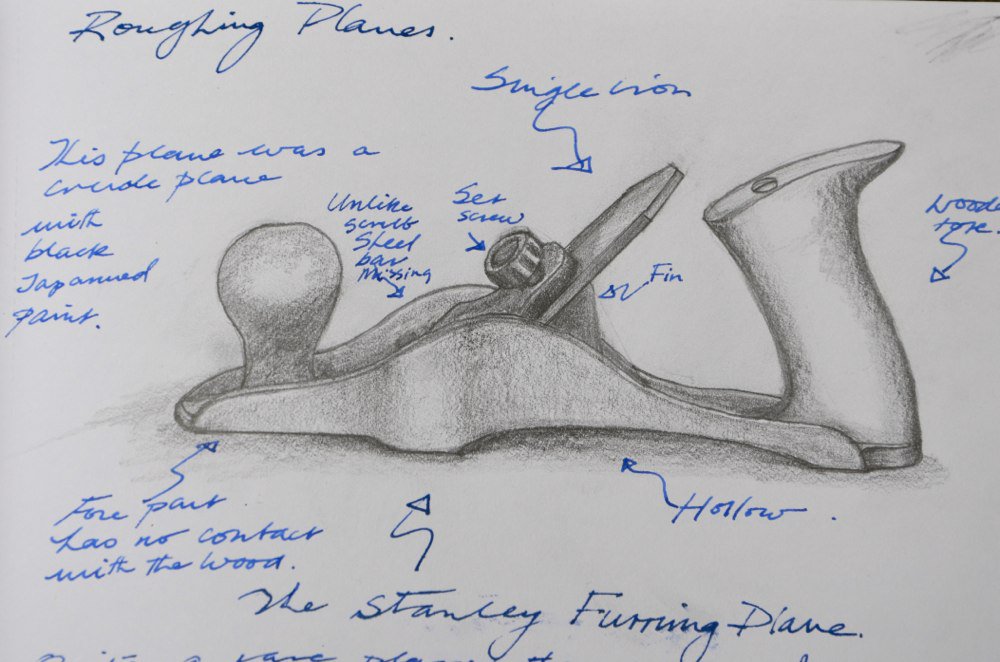

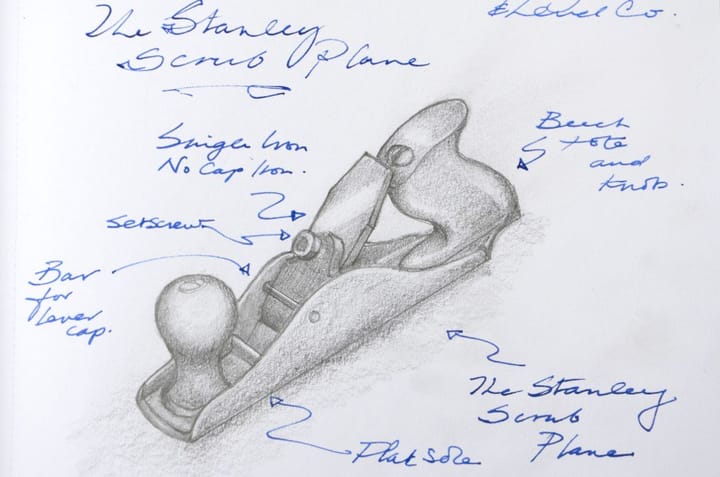

Had I said roughing planes, only a few would have understood. Even in the 1960s old wooden planes, the Stanley scrub plane and even the Stanley furring plane would have been referred to as roughing planes because, in typical fashion, the plane derived its name from its function.

In my dim and distant past (yes this is me 25 years ago or so) I worked with many men 40 years older than myself and all the way up to being 80+ years old. My personal tools then were all squeaky new of course, but the tools in the tool chests and joiner’s boxes these men treasured were all very, very old. Older even than them. I don’t think I was even remotely capable of seeing then that the value in these tools could not be appraised in monetary value but by the provision they were to the men from two world wars in making everything from children’s toys to fine furniture and door frames to coffins. Today, 50 years later, I understand their real worth.

I Keep Old Tools to Work With Because They Work; Not Because They Look Nice

Today many planes from the past are somewhere near to my bench and the throats vary according to use. It’s here that I want to share something i think has value to us as woodworkers. It’s a little bit about the history of planes that may offer insight. In time past I have shared that old wooden planes were never abandoned because they didn’t work or indeed work well. They were abandoned because they didn’t keep pace with the industrialising of craft and the art of work. The whole process of plane making was an art that required great skills in both woodworking and metal working to make the tools of the plane maker. The wood too required specific parameters to produce tools that would remain stable. Though wood was dried in large quantities, distilling this down, a plane blank for your average bench plane, regardless of length, would at very minimum be 5 years before the plane would come from the hands of its maker.

For Centuries Woodworking Craftsmen in Different Trades Made Their Own Planes and Tools

Though wooden plane making ultimately became a specialist woodworking trade within the realms of carpentry and joinery, this only happened after centuries of craftsmen making their own planes according to their given trade. Coopers and wheelwrights, joiners, carpenters, boat builders and 50 others all developed their own specialist planes and tools. Making a plane was a 3-4 hour process and from new the plane served its maker for many decades.

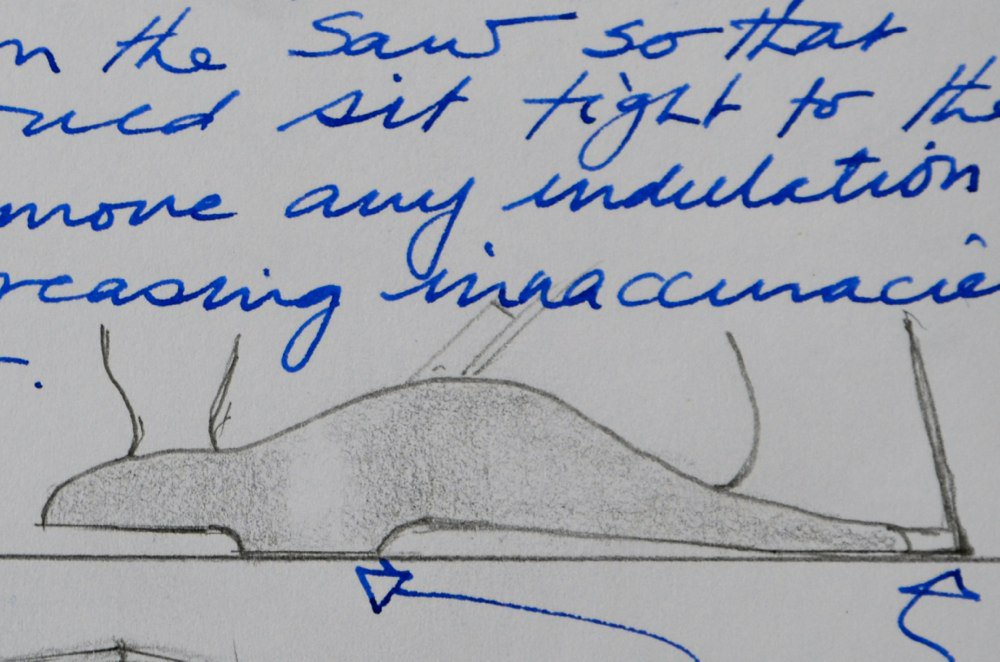

This Image Shows Progressive Stages of Wear and the Resultant Throat Openings Culminating in a Convexed Blade Intended for Roughing.

The Evolution of the Roughing Plane

In the beginning the plane started life as a plane with tight tolerances. Cutting edges were bedded only 1-2mm from the front aspect of the sole , which created the closed throat needed for fine shaving work. Such a plane brought into service for close and fine work would work for a decade or so before wear began to take its toll. It made sense to create a new plane alongside the more used one as the wear became apparent but before too much wear took place. That being so, the new plane would run alongside the older in tandem in the same way a shepherd runs a new dog alongside the old so that he’s never without a dog. As the original plane sole became worn and needed truing because of wear and unevenness, the mouth opening became marginally wider and more open. Another decade and the mouth would be too wide for fine work and so the second plane began to replace the first. It’s at this point that the craftsman transfers the original plane to its new work working the distorted surfaces resulting from air drying wood and saving his finer plane for finer work. The cycling continued and three or four small smoothing planes would see a craftsman through his decades as a working craftsman.

Wooden Planes Performed Exceptionally and Were Never Replaced By Anything Better

Now then, try to remember that these wooden planes were not simply old fashioned models being replaced by something better and newer. That wasn’t the case at all. Also try to remember that they weren’t called scrub planes as we know the term either. They did however perform the same task. It’s important to know that woodworkers were using wooden planes for these different tasks for centuries and that they were in no way inferior to anything produced with modern-day all-metal planes. These crafting artisans in wood resisted the introduction of the all-metal cast iron and steel planes with legitimate cause. The reason they resisted the new planes was not that they shunned change for the sake of it or were merely nostalgic, but that their wooden planes were, in their hands, flawless designs in functionality in every way and actually worked better than the new all-metal ones. They were much lighter in use, almost frictionless in motion wood on wood, were more stable and they could be refined whenever or if needed. Cycling through three or four planes made from the off cuts of a beech table or bed leg was simply the practice of the day. Running planes side by side meant staggered stages of wear levels in the throat and so planes were adapted and adopted to different levels of roughness for the removal of undulation and twist to rough prep boards for the jack and jointer planes. The shorter the sole the kore localised the ability to rough-down highs and of course the easier to turn the plane to task in tackling grain variance of direction and so on.

Ultimately, planes with large and open throats could scrub off masses of wood.

The Scrub Plane Emerges

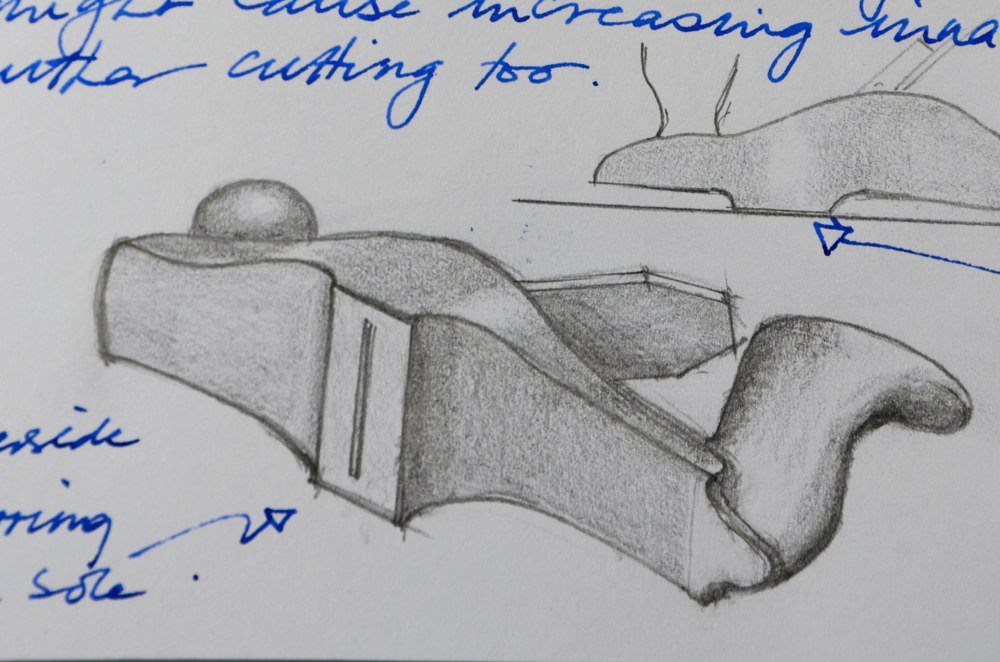

So, as you can see, when the wooden planes were ousted by the cheaper alternative all-metal ones that required only assembly-line production, it became only a matter of time before one replaced the other. Add into that the demands of a world war on timber resources for every aspect of industrialism and you suddenly begin to see how the demise of the wooden bodied planes took place. Machining in woodworking lessened the demand on hand methods too, to the point that one, by one, the wooden planemakers of Britain and Western Europe began dropping like flys. In tandem with the demise the need for a roughing plane made from metal was needed to replace the wooden versions. Remember there was no secondhand market for planes as we might know it now in the sense of family members selling off their great grandfather’s old stuff and certainly no world wide web. The term scrub was most likely in use long before Stanley came developed their version in the all-metal scrub. There can be no doubt that Stanley adopted the descriptive name and so created a special plane in a category all of its own. Though still a crude looking plane compared to all others, the Stanley scrub could initially be mistaken for a very unique and different plane altogether which is the much rarer Stanley #340 furring plane. I only ever saw and owned one of these planes, primarily because it was a US development in planes and made only in the US. I bought mine for peanuts in 1985 as part of a collection of tools and planes owned previously by a working craftsman. Just like the the term used for the scrub plane, furring plane to me implies it was used to remove furry and rough surfaces left by the sawyers after sawing, hence the minimalist surface area of the sole with only four square inches of sole in contact with the wood at any given time as apposed to 11 square inches with the scrub plane and 20 square inches with a regular smoothing plane. frictionless humped area around the mouth and the hollows either side to the toe and heel.

Those operating the machines would use the plane to take off furring from the ripped wood before second and subsequent passes on the saw if the wood had deviated slightly or left too much furring on the surface. The plane would be used both with (along) the grain and at a tangent to the grain equally. This plane will most likely never be replicated because its use is so very limited.

We Lose the Art and Craft of Plane Making

In all of this we saw a close to an era; a tradition of craftsmanship destined to die, save for one or two lingering makers who continued into the early 1960s. For a few decades wooden plane making died and became extinct and to a great extent that has remained the same. Two or three individuals in the USA and the UK have become independent planemakers intent to develop their own niche market for making and selling wooden planes made by hand. There are enough collector users to keep them in business.

Comments ()