On Marking Gauges Part I - Old and New

On marking gauges as a whole - Part I

First of all let me take the unusual step and say I have lumped three different gauge types under the one heading as I have done, ‘marking gauges’, for, regardless of specificity and nomenclature, what they do is what they are. Beyond that, the names help us when we pass them to one another in the shop or write about them as we are here. The names identify the tool for our convenience. We use only three different types of marking gauge to run parallel lines lightly into the surface of wood to guide subsequent work with other tool such as saws, chisels and planes. The lines are made with single and double pins installed in the gauges on a part we call the stem or beam. We use different marking gauge types throughout almost every area of woodworking and a wide range of specific tasks from laying out recesses to marking out the parts of joints before cutting the actual joint parts.

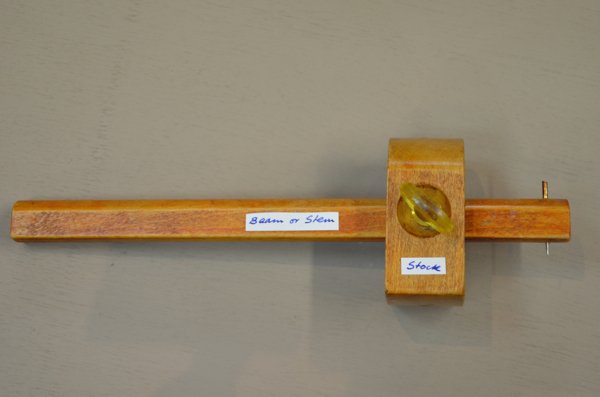

Here is a traditional marking gauge with the two main body parts identified.

Marking gauge types

Marking gauges are quite simple tools and there is not really too much to be said, yet my experience tells me I should share what I know from using them daily this past 50 years. Few modern gauges give us what the pinned versions of old offered and still have for us. There are one or two modern gauges of quality but in my view few match those made in previous centuries using ornately configured brass wear plates inlaid into solid and stable exotic woods such as ebony, rosewood, boxwood or mahogany. Some older gauges might be utilitarian with no redeeming qualities other than the fact that they really work well while others come as highly engineered units but perhaps unnecessarily so. That said, beyond appearance, the most utilitarian gauge gives exactly the same results as the ornate counterparts and equals all of the modern ones in functionality too.In general use, different types exist for woodworkers and at first glance it would seem confusing to anyone new to woodworking as to what they do, how they differ, what they should be looking for to buy and what to use. So, let’s have a go at demystifying the offerings of three centuries.

As can be seen above, marking gauges are basically two sections of wood united together with one or two steel pins passing through the stem part that score the surface of wood to make guidelines usually parallel to the edge of a piece or part of wood. We’ll cover that in the next two paragraphs.

Traditional marking gauges

Traditionally, marking gauges dating back several centuries divide into two main types with a third offering that combines the two types in one gauge. The two main gauge types are the marking gauge and the mortise gauge. The third type is one we call the combination gauge and this one combines both the marking gauge and mortise gauge using a single stem housed in the stock of the same gauge.

The mortise gauge

The combination gauge

The conventional marking gauge

Most marking gauges made through the past three centuries have been made from beech, a straight-grained domestic hardwood growing throughout Europe and parts of north America. In functionality and general appearance the marking gauge remains unchanged after two centuries and more of developed use. In its simplest form this gauge comprises a single stem of wood known as the beam and a shaped stock designed to fit the hand, hold the stem and secure the stem to the stock during use. The stock houses the square or shaped beam which passes into and through the stock at 90-degrees. The stem holds a single, round, steel pin about 2.5mm in diameter fixed near to one end of the beam as shown.

By moving the stock to the desired distance from the point of the pin, and having locked the stock to the beam by turning a thumb screw or setscrew, we push or pull the gauge along the edge of a piece of wood and score a parallel line or lines along the surface of the wood being worked to guide subsequent work with cutting tools such as planes, saws and chisels.

The modern marking gauge

New gauges have been developed in more recent decades, mostly by newer tool makers looking to develop new and innovative tools or replicating high end tools for the more recently developed market catering to tool collector-users. These gauges use hardened steel discs anchored to the ends of twin or single stemmed rods that pass through a metal stock which has a thumb or knurled set screw that locks the beam in the stock to the stock in like manner to the conventional marking gauge. Instead of a pin tracing lines on the surface of wood, the disc engages the wood and actually cuts a very thin knife-like cut line into the surface. These seem highly refined and whereas they give a very fine line on the wood, I often find them too fine to see because they incise-cut the wood so thinly and the wood springs back to close up the line. Having tried the different disc-type cutters over several years I have decided their best use is for two areas; one, they are good for developing hinge and lock recesses, things like that, a very limited use, and, two, I also find them very functional for delineating straight inlay work and for developing cockbeading rebates. Beyond that I find traditional marking gauges that date back centuries have proven themselves invincibly reliable for both longevity as lifetime tools and efficacy in ease of use and simplicity. The discs on disc-type marking and mortise gauges tend to edge fracture along the super thin cutting edge and this seems to easily happen even without careless treatment.

I passed my gauge to John this week and asked him what he felt when he used it. He moved the gauge with difficulty along a piece of sapele, a medium to light density wood, and the edge broke before our eyes leaving another section on the edge of the disc of 2mm missing. The engineering and material quality of this gauge is excellent, but herein is a reality comparison. I suspect that this is another case where an engineer thinks we need something super thin, which is not the case at all. A steeper bevel wall would have given us the a good line without compromise. The disc would be easily sharpenable for a once a year touch up too. Of course this may vary between different makers and even between the actual discs but the fact is they are very, very fine, in my view generally unnecessarily so, and they break easily. On the other hand, I have yet to wear out or break a pin in pinned marking or mortise gauges though I am sure it has happen. With all of that said, in actuality the disk gauge actually works fine with the fractured edge. Perhaps a serrated edge would be another innovation too.

Comparing the two types

In my view modern developments in the gauge in no way replaces the performance and ease of use that the conventional marking gauge offers to woodworking. The two types offer different possibilities and I like to have both with the additional disc type being kept for more special work and not to replace the pin type gauges. That being said we should consider why the two exist. I have found both gauges handy in my work but the ones I generally reach for are the conventional wooden ones. This is not because I am used to one and not the other or I am nostalgically attached. The marks left by the older gauges are clearer to see in just about any and all wood types and the marks made help me to align tools such as chisels exactly to the final line. The pin gauge forms a small but refined ‘U’ shape in the surface of the wood and because I set the very point of the gauge pin to the depth or width of cut, the pointed bottom of this slight ‘U’ then is the exact depth I plan on cutting to whichever cutting tool I use. Another thing I like is the gauge traces the surface easily in all woods and that I have found consistently is not the case with disc-type gauges. In almost all hardwoods the disc gauge binds in use and the manufacturers say not to press down hard, inevitably the gauge seems to pull itself into the wood and indeed bind. This is most difficult and so I find myself using great force forward (not downward) to effect the marking I need. Often times the pinched disc becomes immoveable and especially is this so in oak whereas In self lubricating woods such as some of the softwoods such as pine that’s not the case at all.

These pins are about 100 years old. Use time cannot be calculated but it will be many hundreds of hours.

This disc is used occasionally and over five years the disc has deteriorated. Use time is about six hours.

This picture shows the comparison between the heavy pressure of a pine-type marking gauge on the left, the light pass with a pin gauge at centre and a disc-type cutting gauge at right.

Comments ()