Questions Answered - Why Crosscut-pattern Saws Dominate - Part I

Question:

Hi Paul,

Reading past articles and watching things in your videos it seems you sharpen saws only in a rip cut pattern when most saws available here in the US are fleam-cut and not rip cuts. I wondered, why do you not sharpen a fleam pattern for crosscut saws and a ripcut for rip saws or why you teach only one way? I think it might help if you can tell us what the difference is when using only a rip saw pattern on all of your saws. Do you not rip out the grain when cross cutting if the teeth are not actually severing the grain knife-like?

In anticipation,

Jack

Answer:

In an ideal world it might seem to make sense to own saws with dedicated cross- and ripcut patterns in each saw type and size. That's what many saw makers are indeed telling us and now selling us. Following their recommendation you will end up owning a six pack of back saws and four handsaws. With current makers selling such saws anywhere between £50 and £150 a pop the money stacks up and, without exaggerating, it seems you could be spending in the region of £700-1000 plus on just saws.

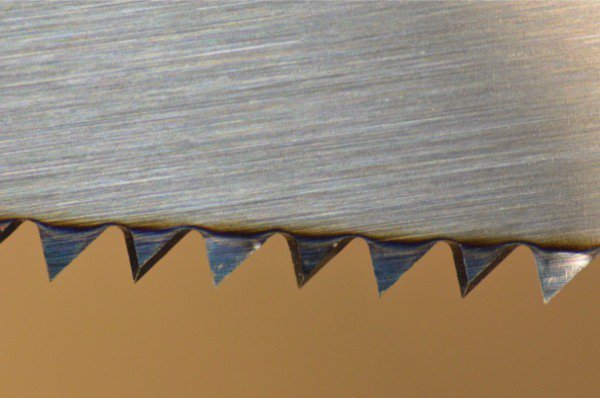

Splitting saws into two dedicated tooth patterns for sharpening in general is unnecessary. I have used rip cut patterns throughout my life as a woodworker involved in general carpentry, speciality bench joinery and of course fine furniture making. In general the patterns I use were handed down to me. However, I have further developed my own patterns to improve what I was taught; to ensure that one saw will cut equally well in both aspects of sawing. I wanted and needed this versatility to make me efficient without losing effectiveness. I think that these patterns were and now remain more the craftsman’s practical solution to effective saw sharpening that keeps them in the zone as they work so that for their general work there is no need to switch saws during tasks requiring cross and ripcut in close proximity of cuts.This differs from advice given by way of the engineers manufacturing saws that if left to their own devices and marketing strategies have us straining at gnats like they do with other methods of edge tool sharpening of hand tools.

I actually like to sharpen saws - any type of saw, so when I come up against one that says you can't sharpen it, something rises up inside of me until I can better understand why. As I started out, I actually like to sharpen saws and for several good reasons. More on that later. It’s never a chore for me and I usually get the results I want in a particular saw in about five minutes regardless of size and or type. First of all, I have several saws - about a hundred. In reality I reach for about eight. The same number described above. Tooth sizes require different saws as a general rule and for different reasons. The rest are used in the schools or are in for restoration work and filming the processes. Seven of my eight saws are sharpened to a ripcut pattern even when I use them equally for rip and crosscutting. The makers of saws obviously prefer to sell two saws instead of one. To my recollection as an apprentice I never heard anyone say pass me that ripcut saw or that crosscut tenon saw. No one called a small saw a dovetail saw and the terms carcass, sash, back and gents were not actually used. Of course men I worked with knew names of saws and we knew what to hand them but i knew by the task in process. Somewhere around the 1980’s we saw the two saw types emerge and we saw progressive tooth sizes return to specialist hand tool woodworking; this happened alongside hardened teeth sharpened to the crosscut fleam-pattern for working 2x4 construction from dimensional lumber and the so-called engineered boards used throughout construction. Talk about a confusion!

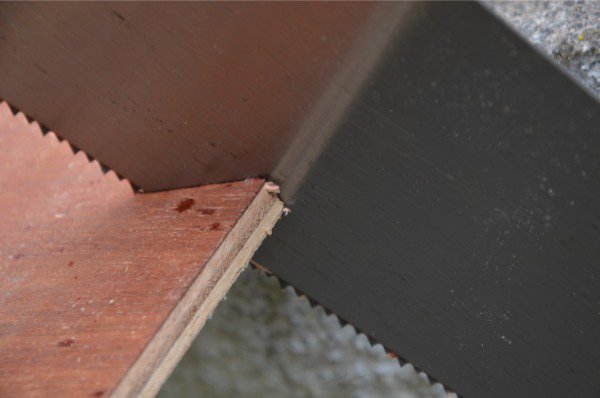

If you consider construction work today it has very little to do with actual joinery and so too joinery has very little to do with using hand tool methods for construction. What the construction trades needed was a throwaway saw that could basically perform tasks that might be prohibitive on site. Whereas all tasks can be performed using the ubiquitous chopsaw and skilsaw, in any given day a site worker needs to cut out a corner or a shape that defies using power equipment for many different reasons not the least of which is size. Skilsaws will indeed rip down 2” stock to any angle and parallel in a heartbeat compared to say a conventional handsaw. Pressed fiber boards like OSB are made up of strata laid flat in manufacture but effectively, because the orientation is so diverse and unpredictable, all cuts are crossgrain cuts. Plywood is always either side of fifty-fifty crossgrain cutting also depending on which direction you cut in. Using a skilsaw you can barely detect any noticeable different but a crosscut saw always cuts better than a ripcut. MDF has no grain to speak of and chipboard is the same. So you can see why in certain trades the fleam cut modern construction trade saw displaced the traditional saw on the construction site in general and in joinery too because of course the work done in industry is almost always machine work.

Of course furniture making is no different in that it's no longer so much a craft outside of a few individuals choosing an alternative lifestyle but a mass-manufacturing process using machines. Most furniture made for homes today is manufactured and no hand tool ever touches any surface. The craft has indeed died.

Once you see why saws made for big box lumber and building suppliers don't really suit general woodworkers and furniture makers, you start to see the niche market smaller specialist makers discovered and developed. I'm glad they have, but most woodworkers cannot afford to buy into the multiple new saws syndrome. Tomorrow, all being well, we can look more at tooth patterns.

Comments ()