Edge Fracture - Is It More or Less Likely With A2 Steels?

These past few days I have been working more with bevel ups and bevel downs and in my R&D mode I have found all the more questions in the different steels people are using as well as the plane types and so on. We sharpened to different angles to see what happened at different angles of presentation and looked at carbon steels used in plane making in the pre 1960’s and then A2 steels and others offered by most modern-day planemakers. Different planes installed with different plane irons gave surprising results. These images presented below, whilst in no way definitively scientific (yet), show contrast I found between harder A2 steels and the commonly used carbon steel.

You see, in using two different planes, one a bevel-up and the other a bevel-down, I found that the bevel-up plane with an A2 (harder steel alloy) began to ‘climb’ the surface of the wood much earlier than the bevel down. In other words, after 50 full length plane strokes along a 1 1/4” (30mm) wide by 48” (1.222mm) length of red oak with each plane type installed with different steel types, the edge fracture was much more apparent in one than the other. So markedly different was the obvious visual difference I became totally absorbed by it. What I saw visibly at the cutting edge with an unaided eye was further substantiated by the physical effort it took to effect subsequent cuts.

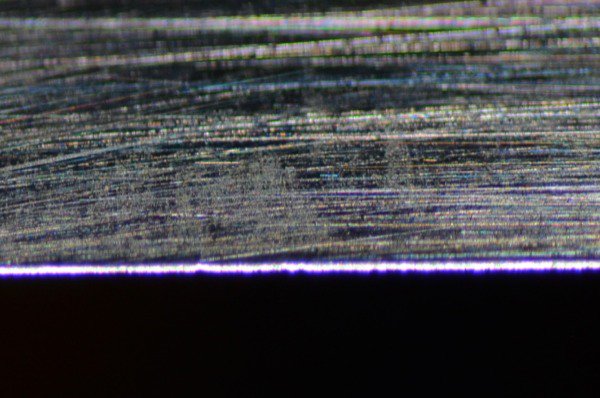

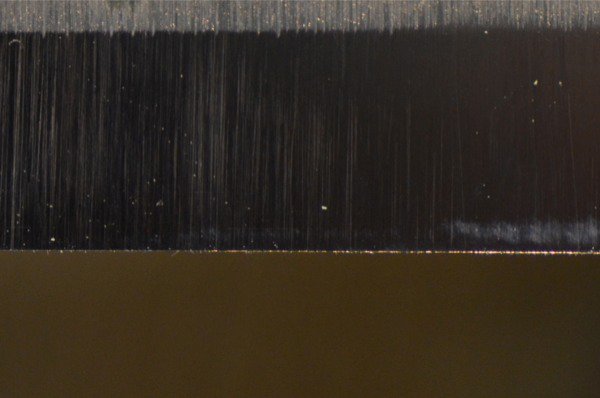

The image on the left shows the edge fracture showing on the flat face of an A2 steel blade in a bevel-up plane. The purple line (fluorescent light) shows light reflection off of the leading edge . The one on the right shows the edge fracture on the bevel face of the same plane iron; the bevel up side. The right of the image shows near the centre of the blade where most of the work took place at that 1 1/4″ section of the iron.

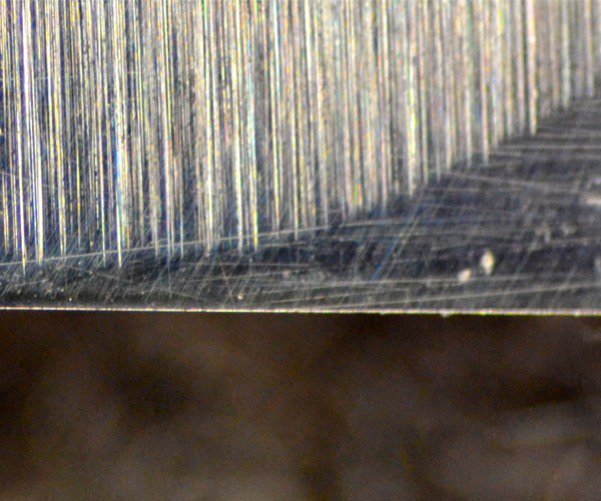

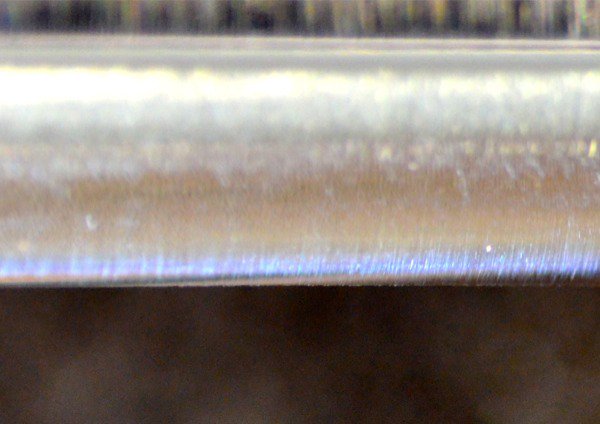

The second pair of images above and right show an iron from an older I Sorby plane I use regularly now. After the same number of strokes the edge fracture is markedly less on the flat face of the cutting iron compared to the harder A2 steel from the bevel-up plane (shown in the first two images above) and also on the bevel side of the same iron. I noticed that I had to push harder sooner on the bevel up plane than the bevel down plane because the plane began to ride the cut because the fractured edge on the flat face created a sort of rounded or convex corner to the flat face of the cutting edge. This means that the cutting edge was no longer pulling itself to task but pushing the plane up and over the surface. This is generally the most principal way we can tell that it’s time to sharpen up. With the bevel down plane this began to show only when I neared the closeout of the 50 strokes.

This work piqued my interest and helped me to understand that the jury is all the evermore out on plane types, bevel types, steel types, iron thicknesses and much more. Time to dig much deeper I think. The proof is at the workbench where I discovered the wood ‘climb’ and not only in the lab, but I want to understand why we found what we did and perhaps if it is a consistent finding. We could just have a poor iron. On many older English irons used in wooden bench planes of course the steel was laminated, as with some Japanese planes. these planes had toughness and hardness. i will be looking more at these irons too. Did we lose something in our progress?

Comments ()