Salvaged Saws Survive as a Legacy

I found a tenon saw two weeks ago and picked it out of the basket of junk smothering it. It seemed sad, uncared for and out of place. I did have some sympathy for it and as I traced my fingers along the dulled teeth I considered putting it back down. I do that a lot. In my eyes it was worth a pound or so and I asked the lady, “How much?” She surprised me when she said, “Four pounds?” I surprised myself when I said, “OK.” My eyes traced a bead along the teeth like I might sight down my old Smith and Wesson 38 in my former life. She was surprised when I pulled the four coins from my pocket and placed them in the palm of her hand. “Why did I pay so much?” I asked myself as I tucked the saw under my arm and walked away. It looks like a junker and you have a hundred tenon saws. Something told me there was a bit more depth to this saw and it is harder to find 14”, 16-tpi tenon saws secondhand these days. But I think it was more the lady selling the saw that I felt respect for that affected me. Yes the saw was a much neglected specimen. It was unkempt but my inmost considerations proved right. The saw had belonged to her late husband. She knew he bought it with good intent, valued its worth, bought the best he could afford and used it as much as he could before it went dull. The asking price became fair to both of us and for me, I wanted to refine my find to better condition than when it was new back in 1945. I wanted the saw to work like it never had and I wanted it in the hands of woodworkers not the landfill.

I left the saw alone by my bench for two weeks and picked it up from time to time. The restoration appeal grew each day, but patience and a heavy workload said wait. I sensed something hidden beneath grime, oxidation and crumbling varnish wanted out. Some modern saws leave me feeling that way too. Yesterday I lifted the saw to my eye once more to remind me of the needs. No kinks, thankfully, but what lay beneath the grunge on the plate? Before deciding anything, I place my Groves on top of the unknown, no maker’s marks anywhere, and see that parts parallel the flow in the newer handle, yet aspects seem stunted by a phase in modernity. I see that the similar parallels connect through a span of near 200 years. Imagine that preservation anchored in a design. Why did we stop. Utilitarianism resulting from two World wars was over. My Groves 14” matched several details of the new find. The angle of presentation of the handle to the line of the saw identical. Both handles were beech, of course, but my Groves felt like an old glove-fit as yet unmatched by any modern maker but close to in one or two.

The handle came loose easily and the brass screws parted from their dimpled recesses beautifully. Reshaping came quickly with the smaller Auriou rasp. I think they should sell the rasp as a saw handle rasp. It’s the most perfect rasp I have ever used for this purpose.

I am sure there are other makers too. But this one gets you there fast, really fast. Sanding is minimized and your soon done with shaping. In an hour my saw felt no different than my Groves. That’s a good starting point and I have shortened perfecting by two decades.

The plate surfaced quickly and without any pitting. I was glad, but pitting is only aesthetic and such physical defects make no difference to functionality. The brass started shining but the original was not smoothed like old saws were. I took it up several notches with abrasive to 2400 and then buffed with buffing compound and cotton mop. So too the heads of the bolts both sides. The domes glistened in the sunlight. Two primers of shellac thinned to sanding level and with a little colour mix I dyed the handle close to where I liked it. All that’s left for tomorrow is wax.

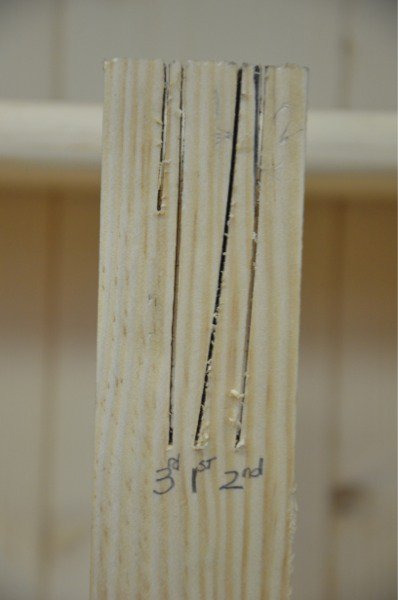

Before sharpening the saw curved in the cut, which took 50 strokes to bottom out. After sharpening the curve was less and the number of strokes was 18. After I knocked of most of the set the saw cut to line and took 14 strokes.

Comments ()