Sharpening - Hard facts you can work with (video)

Sharpness from keen observations - What do we really see as sharpness and what do we really need? Could sharpening to task be significant and practical?

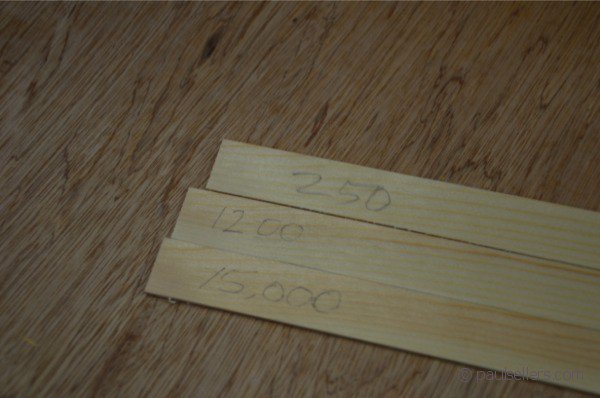

These three levels of sharpening leave the wood feeling only marginally different, look virtually the same and are all sufficiently finished for sanding and finishing

What does 'sharp' really mean in real terms? Sharpness is a relative term. One day everyone will believe that that the only best edge is one with a micro-bevel sharpened with a honing guide and polished out to somewhere between 15-25,000 grit. Such is the dynamism of living on cutting edge technology. Once persuaded toward this methodology, it's difficult to shift to any alternative that doesn't have at least the appearance of being more demanding. And it's this rigid strategy that somehow displaced the more free-forming methods of past craftsmen who , well, simply sharpened and got back to work. This blogpost might help to cast a different, alternative light on what is effectively a simple task complicated by, dare I say it, over-information.

More controversy surrounds the essentiality of sharpness today than ever in the history of woodworking. I think it could be another of those things created by disposable time and disposable income. The question I ask myself is is it obsessive to know more about the steel and give it new titles and facts about edge retention than to know what the tool with the edge can and cannot do? Is it more important to sharpen to tens of thousands of grit sizes than to be able to plane the edge of a door to fit without binding or level two adjacent surfaces in a frame?

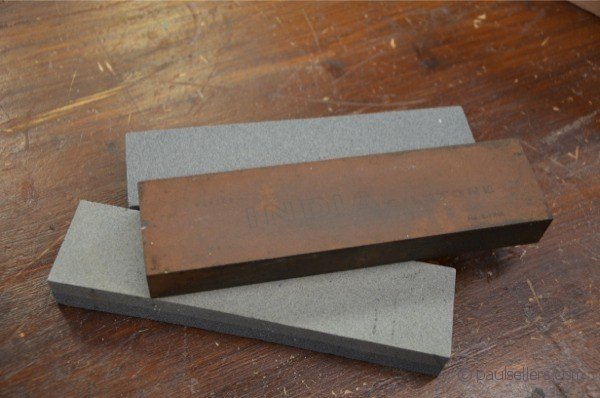

As a boy in my joinery-apprenticeship days, most of the men were caught up in the art of working wood and and the sharpening methods and stones they used seemed almost but not quite inconsequential. They sharpened their chisels and planes as they dulled and got on with it. Some men used Arkansas stones and some Washita (softer and more friable) followed by an Arkansas, Turkey, India or Slate whetstones. The thing was that all of the planes and chisels worked perfectly well for planing, chopping and paring. There was no conversation about one stone over another. It does seem more and more that this once very simple act and fact was radically changed. Today I receive more frustrated emails from people than ever before. Mostly because of a variety of reasons not the least of which is that they rely on learning from internet sources and of course with a zillion opinions out there, they cannot find what they are looking for. Stones and plates, slurry powders and diamond pastes. Tormek, Worksharp and all of these ‘things’ that promise perfect edges effortlessly in seconds are actually, for the main part, slow, time wasting and controlling. More than that, the men I worked with sharpened mostly to between P150 and P400 using stones for close to what you get with the Norton Combination India stone, which is a two-sided stone with coarse p150 on one side and p400 the other. The 150 took out small nicks from hotting nails or grit and the 400 polished the edge to give it a cutting edge for planing and chiselling. Some of the men had an additional stone called an Arkansas stone and they used this to gain a better, more refined edge, but this was reserved for occasions of finer work and not resorted to for daily sharpening. So this is where I diverge from what has very much become the norm. Visiting woodworking shows for twenty and more years I have seen something emerge that has created a false impression of craftsmanship. It happens in most woodworking magazines too. Demonstrators spend an hour developing a perfect edge, find a perfect piece of wood to shave and remove a shaving a full two inches wide and half-a-thou thick and float it in the air in front of an audience struggling to get a shaving of any kind. The question is this. Have we become an obsessing phenomena when it comes to sharpening a plane or chisel? There is a good possibility we have, but we may not know it. On the other hand it could be that people were held in the dark ages by a lack of the superior knowledge we have about sharpening today. Lets try to take a look at what I think we might all be seriously looking for.

Just what do we want from a cutting edge when it comes to chisels, planes, knives, spokeshaves and so on? Working with woodworking enthusiasts, new and seasoned, I think we can divide the woodworking world into two or three camps, but not equally. I meet people and have friends in one camp where a Saturday morning can be spent sharpening an edge on the very best equipment to bring the best of the very best tools to a level of perfection most others might never achieve. They then spend the afternoon of the same Saturday shaving shavings from beautiful woods like figured maple. The engineers callipers measure the thicknesses of the shavings thousandths of an inch thick and of course their enjoyment was the festoon of shavings floating from the wood to the floor. They then put the tools away until another Saturday comes around and the ritual is started over once again. Of course in this category the goal is the shaving and not necessarily the finished wood or the woodworking that needs shaving. The category is small, very small, but all too often this group perfected the plane setting and the shaving of fixed limits but never went on to discover the expanse of woodworking and where they might invest what they learned into a more comprehensive field encompassing joinery and fine musical instrument making, other woodworking crafts and so on.

Subsequent groups splinter off into a wide range but in the broader range. They are those who want to work wood whether they do it for a living or as an add on to their normal world as a second, income or non-income producing occupation. This group concluded early on that they must have a degree of sharpness to their edge tools and that they must be able to achieve a sharp edge if they wanted to indeed work wood with hand tools. They found the information they needed and started sharpening their tools to similar perfected levels without thought that they might be obsessing over achieving the edge without realising that that was indeed what they were doing. The question then is is it obsessing, or necessary, or practical to go for the so-called "scary-sharp" level of sharpening every time we sharpen our tools. Is it more practical to sharpen to task than to always reach for that surgically-sharp higher-ground cutting edge in pursuit of the perfect sharp edge we are now led to believe to be standard.

There is no doubt that when what you make has nothing to do with earning your living, and in an age of disposable income and time (remember somehow the Brits have 5 1/2 to 8 weeks vacation time a year), we can indeed spend time developing edges that take the chisel edge to new heights. In the new absence of at-the-bench, on-the-job training between master artisan and apprentice, we now have the salesman and magazine. In the land of the blind the one-eyed man is king, remember. They, and you, now stand in the aisle at the woodworking show buying and selling planes as a result of whisking off lace curtain shavings you can see through one after the other and full length at that. He’s talking the whole time and my goodness he looks to be doing it with such ease and peace. There is of course no knot in sight and he’s using “curly” maple that looks impossible to plane. You, on the other hand, are glued to his left hand as he lifts the shaving with each stroke and floats it away in flurried sweeps to fall weightlessly to the floor. You’re hooked. Is it the plane he’s selling that achieves these incredible results? Is it the honing oil? Could it be the honing guide or is it the stones and plates lined up in succession? “I have to have whatever it takes.” you say to yourself. But what you may not see is how any of this does any more than take a perfect shaving with a perfectly set plane on a perfect piece of wood. How do these perfect shavings apply to woodworking in reality?

Sharpening does not need to be an obsessive task unless of course you want it to be, in which case it may not be obsessive but undeniably fascinating. It can simply be that the end product you want is the shaving you can see through. All the time these days I read someone’s statement that to test for sharpness you pare the end grain of pine to see if the surface is pristine and shiny and the removed shaving singularly unfractured. It’s a bit silly really, but, again, somehow this has become the standard in the same way micro- and secondary-bevel sharpening has become standard. A chisel sharpened to 400-grit will chop hinge recesses on house doors just fine and effortlessly and so too a plane sharpened to 400-grit will plane the bottom and stile of the same door perfectly smoothly and more than adequately for painting or varnishing.

Sharpness appropriate to task. The fact is that there are levels of sharpness appropriate to task. My son Joseph is a violin maker and when he sharpens he sharpens his planes to about 25,000-grit. He takes each tool through the various levels of particulate diligently, so that the cutting edges cut crisply and flawlessly. This affects the sound of the instrument he is making. On the other hand, as a joiner, I never sharpened to more than 400-grit and neither did the men I worked with. I chopped thousands upon thousands of hinge recesses and chopped hundreds if not thousands of mortise locks using a bevel-edged Stanley or Marples chisel sharpened to no more than 400-grit. Transferring to shop fitting and architectural work I then began to sharpen to finer levels between 400 and 1,200-grit.

When I worked making furniture I moved my tools toward 15,000-grit and pretty much stayed there because once you have abraded to 250, subsequent grits take very little extra work and effort. Going from 1,200 to 15,000 is only 30-40 extra strokes on the strop. Does this make a big difference? Well, there's no doubt that it does, but let's take a closer examination.

Here I have three planes each sharpened to different levels. One is sharpened to 250-grit, the second to 1,200 and the third to 15,000. I plane subsequent shavings from the same piece of wood. My feeling, that is what I feel in the plane as I use it and not mere opinion, is that the plane cuts perfectly fine but I feel more resistance than when I hone to higher levels. The surface of the wood feels more than adequately smooth and I cannot see or feel any surface roughness that needs resolving with sandpaper. This then cuts my sharpening down by about two thirds. Taking the plane edge to 1,200-grit I can feel marginally less resistance as I push but my fingertips cannot say the surface is particularly smoother than to 250-grit.

Don't feel left out if you cannot afford the upper end levels of sharpening straight off the bat it does not generally matter. Depending on your work, you may not need to. I think if you were to try what I suggest here you might be surprised by what you find. My objective here is to say you need only one sharpening level. It could be 250, 400, 600, 800 or 1200. Using any one of these will give you a sharp plane or chisel that will cut and smooth wood well. Any one of these levels will give you a cutting edge that will plane and chisel wood to a smooth level. Any one of these levels will give you a cutting edge that will plane and chisel wood to a smooth level. Which ever level you like or feel most adequate to task is the only one you are likely to need. This is especially so in the initial stages of learning and acquiring the tools you need and when finances might be the biggest challenge. The chest above would have looked the same whichever grit I used.

Here is a video that might help you and indeed show that even without obsessing you can get good results from a chisel and plane.

http://youtu.be/UbAo4RpM7oM

Comments ()