Framing the issues...

...determines the outcome

It's said that the one who frames the issues determines the outcome. With frame saws that may not be so predictable and so I found myself drifting with thoughts of frame saws these past few weeks and the thought crossed my mind that rigid plate steel saws like the ones developed in Britain and further developed in the USA by people like Henry Disston might seem to be a more advanced methodology than say the mainland European frame saw. It struck me then that thin plate was the demand of craftsmen for finer work such as dovetailing and small tenons used in furniture making and so on, but that the plate envisaged was actually too thin for a push-stroke saw without some way of keeping the saw plate from buckling under the forward thrust between hand and wood. Hence the addition of brass or steel splines that allow thinness and rigidity in the same tool.

Thick and thin plate

Thicker plate seemed to be preferred in Western makes of ‘freestyle’ saws as the saws were not pulled into the stroke but pushed, and that then required slightly thicker steel plate. To counter some of the weight and retain strength, Western makers came up with the taper-grind that removed about one third of the weight without compromising rigidity. This also enabled a change in direction for alignment if needed and even a curved cut to a certain degree. Of course thicker plate stock meant more effort and energy in the cut. Adding a rigid back, be it steel or brass, gave rigidity to thin stock and so the Western-style tenon saw was born for finer joinery and furniture making work. In recent years we have seen the Western world adopt Japanese saws and so there has been another trend toward pull-strokes. These saws work well too, but because they are more difficult to sharpen, over time we have seen yet again another substitute with the arrival of the disposable pull-stoke saws mass-made by various giant tool companies. And that’s the kind of saw most people buy today.

Differences do exist between types

A huge difference between push and pull stokes is that the pull-stroke saw almost demands a vise and bench to pull against, and whereas the push strokes work really well on saw horses, pull strokes are indeed more problematic; having the whole earth countering downward pressure from above is a whole lot easier than pulling against your own strength in the same motion. Accuracy too becomes an issue between the two. Which one is backwards seems to me a matter of the culture you are raised in and programmed by.

Mainland Europe’s frame saw

Though of course Britain has long since had a variety of frame saws, most of those in the furniture maker’s arsenal are turning saws. Isambard Kindom Brunel and Samuel Bentham were indeed the first ones to create the vertical frame saw for slabbing trees into boards and this method was used up into the early 1900‘s in some regions of Britain. The frames were huge and so too the blades. It wasn’t so very long before we saw the continuous bandsaw blade we know today.

Frame saws old and new

In mainland Europe and later on in North America, frame saws of every size were used for everything from limbing and logging to fine dovetailing and shaping for violin necks and so on. Many modern-day woodworkers like Frank Klaus use frame saws in their everyday work and on an added note Joel Moscowitz of Tools for Working Wood came up with a most stunning development by simply extending the length of a common coping saw blade, refining the cut, and adding the components for making your own turning frame or bow saw. Joseph uses one he made from the kit parts for all of his shaping work in making violin necks and bodies. It makes a really fine tool. Made using the same cross-beam and stem structure, with tourniquet tensioning to a thin blade pulled taut by the pressure on strings traversing the length of the saw, the saw has a handle and pinion that allows the user to turn the actual blade during a cut, so that the blade can readily follow curved sections in similar fashion to a coping saw.

The advantage of the frame or bow saw is that push and pull stroke both work as and if necessary and for some applications this can prove greatly advantageous. The steel can be super-thin and you don’t need a whole lot of width to the plate for most work. For this frame saw I used a very functional metal cutting bandsaw blade generally used in a hand held power metal-cutting bandsaw. The bimetal steel quality is really excellent and the aggressive non- or negative-rake to the front of the teeth cuts wood along the grain quickly and effectively. Because of the size of the teeth, I can also cut cross-grain with smooth efficient cutting too and so I found that this bow saw can cut small tree limbs and dovetails with equal alacrity and leaves a very smooth cut. I also found that I could rip along the grain or at a tangent, so this answered my quest for a saw that could be used for a range of tasks far beyond those that I could get with a regular handsaw or tenon saw. Of course I am not suggesting that it replaces either. I think that the frame hinders certain tasks that are easier with the British-style saws, but for under $5 I have a saw that adds new dimension to my woodworking and also gives me a saw I can hand to a young woodworker that will give a measure of bandsaw capability without the dangers of a bandsaw machine.

Simply made in half a day

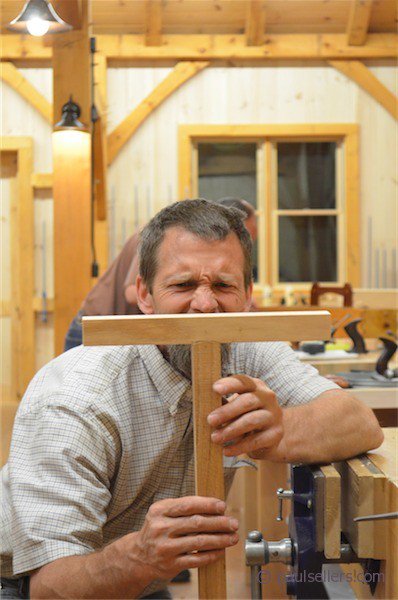

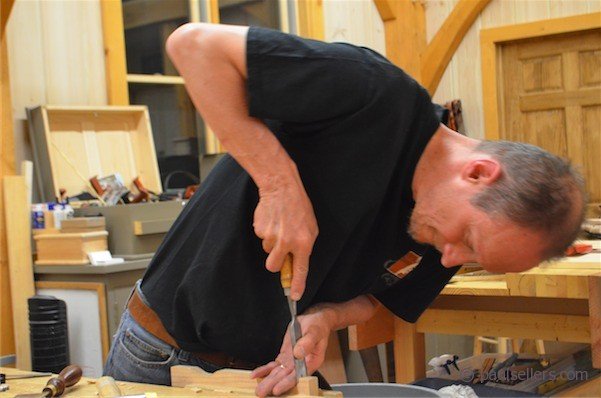

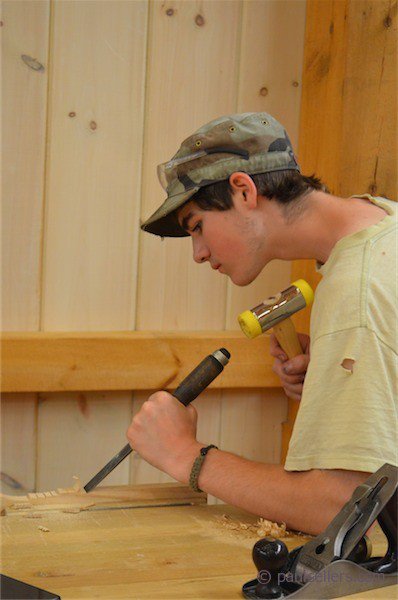

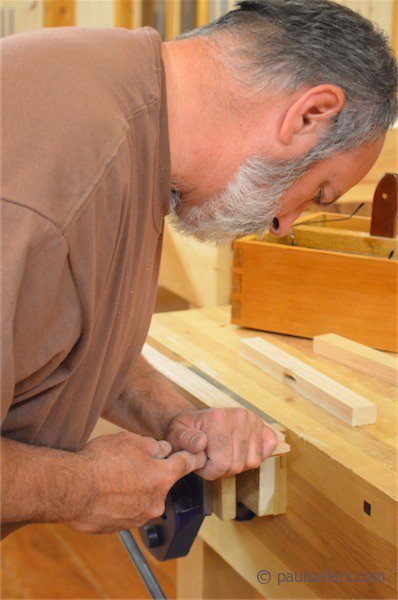

Making the saw is not complicated, even though my two jointed intersections may at first seem intimidating. This is a functional saw and making one is constructive and enjoyable. On Monday evening this week we had a hands-on workshop making this saw with friends and staff at the Maplewood Center woodshop. I made one complete in about four hours, but I also taught it and took two hundred pictures for my how-too as well. By the time the evening was over we had made eight bona fide frame saws that not only worked but worked exceptionally well. Here are the first dovetails I ever cut with this particular frame saw using a metal-cutting bandsaw blade as the blade. Eleven year old Isaac made one too, alongside his dad, David Ashdown. This is just another step toward getting children back into the woodshop. I think too that this is a good step for others who might be intimidated by machine bandsaws. It’s not exactly the same purpose or intent, but it means people are equipped for certain types of work without the inherent dangers machines inevitably bring.

Evidence of work and functionality

Here are my finished dovetails. I also cut a mitered haunched tenon that followed the gauge lines perfectly. You may take an hour to get used to the lightness of the saw and the nuances of flexing to task rather than forcing the saw.

A new series

I am about to do a series on spoons, spatulas and other shaped items and this saw helps me span the huge crevasse between hand and machine methods for those who prefer not to use machines and those who simply cannot use them.

Comments ()