Myth and mystery surrounding plane and chisel bevels

I want to revisit something that proved interesting throughout my tour in the US these past three months. I asked attendees at each seminar what angle we grind our chisel and plane bevels to and everyone said 25-degrees. I then asked what angle do we hone them to? The answer was a resounding “30-degrees” and so I asked them, “Why 30?”

Actually that only became a truer statement in more recent decades. We woodworkers actually sharpened to what we felt we wanted and not what we were told to sharpen to. We woodworkers decided to sharpen a chisel to task so that if we were working on one wood or doing one task, we changed the bevel by eye in a fraction of a minute and got on with the work. Some chisels we sharpened to 35-degrees, but we never ever checked any angle with a protractor, but you can if you want to and I think new woodworkers should check themselves from time to time. Sometimes we changed it to 25 degrees and that worked so effectively for hand paring soft wood. The reality is that there are good and practical reasons that we do sharpen or hone to around 30-degrees for general woodworking, but they may not be what you think they are. For the main part, certainly throughout history, this 30-degree bevel was merely the angle to shoot for, rarely was it gauged and it was not a legalistic and rigid definitive angle. How often we teach this as an absolute in the same way that we say you must freehand sharpen or you must always use a honing guide. The disadvantage of using a honing guide for me is you can’t create the macro camber I like as a bevel. The advantage is you are assured you get the exact bevel you want. On the other hand it can be a bit slower, quite a bit, and it's more fiddly, but perhaps not overly so because I am told you can "get quick at it." All in all there are reasons for both freehand and guide held sharpening methods ,so then it’s a matter of personal choice.

This plane has relief of only 3-degrees less than the bedded angle of the pane and it cuts very nicely; as well as one honed to 30-degrees. Wow! That's freeing!

The issue of the ground or honed bevel is for me an important one because, just like laying the plane on its side became right and leaving it upright on the benchtop became wrong when it’s not wrong and never really was until someone said it was wrong, so too sharpening a plane at 36-, 29- 33- or 40-degrees can be deemed by many as wrong when in fact it’s not wrong at all.

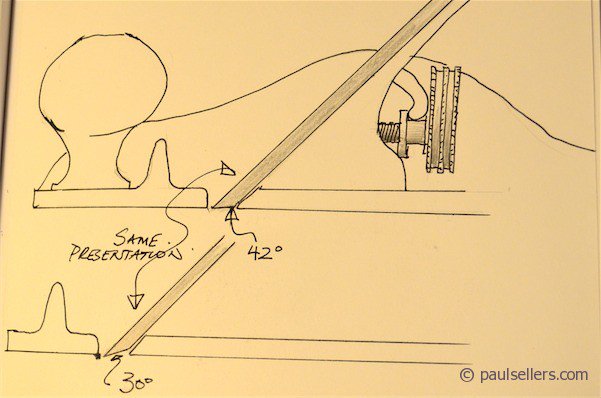

Let me ask you a question. If a bevel-down plane has bedded angle at 44-45-degrees, like all of the Bailey-pattern bench planes and many others are, what difference does it make to the cutting edge if the plane is sharpened at an angle more than 30 and less than 44 to 45-degrees? Surely, as long as the bevel is underneath, it makes no difference to the presentation of the cutting angle to the surface of the wood, right?

At the shows, this was a question I asked and indeed answered. It demystified what was the unasked question, which was who said it had to be dead-on 30-degrees? As I said, the angle of presentation remains identical because the bevel is on the reverse side of the cutting iron and not on top.

The fact is it’s just good sense to have something to shoot for and 30-degrees is a quite practical angle to establish. I never use a honing guide unless something has gone wildly out of kilter. On the other hand, in my classes, I have honing guides for people to use as some prefer to at least start out that way. Ultimately, all of my students end up freehand sharpening because of the speed and efficiency and indeed variability of creating say an instant change to a 30-degree bevel to make it 40-degrees for chopping mortises in certain types of wood or something like that instead of a hand paring angle. Most people have chisels for chopping and others for paring as they accumulate more and more tools.

This protractor shows the exact angle we ground and honed at. No secondary- or micro-bevels.

Yesterday I honed a 42-degree angle onto a #4, bevel down, plain old Stanley smoothing plane and planed pristine finishes on a surface that slightly tore with a bevel-up plane presenting the exact same angle as the Stanley. I have known this all of my life and yesterday Phil and I put the plane through a series of at-the-bench tests to see the results. Now you can start to see implications to this. A 42-degree bevel is much stronger than a 30-degree bevel because there’s a mass of steel right the way behind the cutting edge and all the way back the width of the iron. He presto, no chatter too. Not that my plain, non-retrofit, #4, Bailey-pattern Stanley with its original iron ever chattered in the first place.

Straightedge showing the honed primary bevel in relation to the sole and showing a 3-degree relief at the back edge of the bevel.

The outcome of all of this is to help people understand that the 30-degree bevel is a good and practical angle to shoot for, and when or if you do decide that freehand sharpening is a good option to establish as a skill, it’s best not to think too much about the angle at all, even on bench planes, because it doesn’t really make a whole lot of difference to the actual cut. It is most unlikely that anyone is going to freehand hone anywhere near 45- degrees in my experience. The bevel must be about 2-degrees under the bedded angle of the iron for what’s called relief, that’s all. Otherwise, spring back in the wood’s surface causes the plane to ride the wood and rise up against the cut, resulting in a no-cut plane.

The other thing is that it is easier to sharpen around 30-degrees than it is at 40-degrees because of the steepness and control. If you are freehand sharpening and you are anywhere between 30-40-degrees, the plane’s cutting edge will of course last longer and the plane will cut with exactly the same pressure because the angle of presentation to the wood is identical, regardless of bevel angle. It’s also the same as is on bevel-up planes. So it makes no difference in terms of pressure and resistance. That said, there are physical dynamics at play with bevel-up planes and that’s to do with alignment of the cutting iron to give more inline direct thrust, so you cannot dismiss the efficacy of the bevel-up planes either. I don’t think that its an either other situation and I do like bevel-up planes. You don't have to get bogged down with infinite angles to bevels on planes and should leave yourself with options for change. You are free to sharpen your bevel-down planes with infinite variability. In freehand sharpening, this becomes essential and it makes little difference to the work you are planing so enjoy the freedom whether you use a honing guide or freehand your cutting edges. Try it, let me know what you think. Oh, and by the way. Three planes I bought recently that were old 70-80 years at least, and craftsman owned too, had macro cambers that started at 35-degrees and dropped in an elipse to around 20-degrees. I see that fairly frequently.More on chisels to follow.

Comments ()