Handsaw defined by cultural changes

I often receive emails asking me about more modern saw makers and apart from a couple of modern makers more involved in finessing the finished tools they make, I find myself unable to recommend most of the mass-made saws for one simple reason - hard-point teeth. Is it the hard-point teeth alone that fails the test or something more? Induction hardened teeth mean that a perfectly good saw has to be discarded and at best might end up being recycled if we are lucky. Beyond even that there is another problem and that is that most often these saws have teeth defined by shape for crosscutting wood and when they come to ripcutting along or with the wood grain they just don’t cut it.

I remember the transition coming into place when I didn’t quite understand the first Spear and Jackson catalog entry about 15, maybe 20, years ago. Two saws looked the same or similar, but the first saw said underneath, ‘resharpenable’, whereas the other said, “lasts five times longer than conventional saws”. I passed over the comments at first, but was left with a niggling feeling. Just what was going on here? I had never seen anything said or phrased like this before in a tool catalog and I then realized what was happening. On the one hand there was a conventional saw that had steel hardness at a level that could be resharpened with a three-square saw file whilst on the other the steel was induction hardened electronically and that hardness meant that the sharpness would last five times longer but then could not be resharpened by using traditional hand methods. The problem was this then. What was being implied was that the new saw would last five times longer than the old saw when in fact it was the sharpness of the teeth that would last five times longer. This then led to the first disposable saws we see so highly prized today and yet in the construction trades this now makes sense even though it’s still hard to reconcile making a throwaway saw.

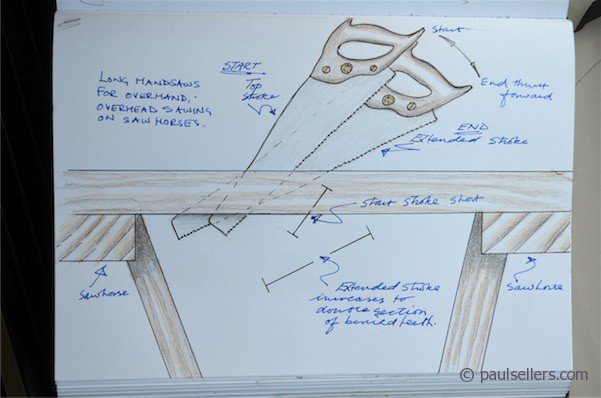

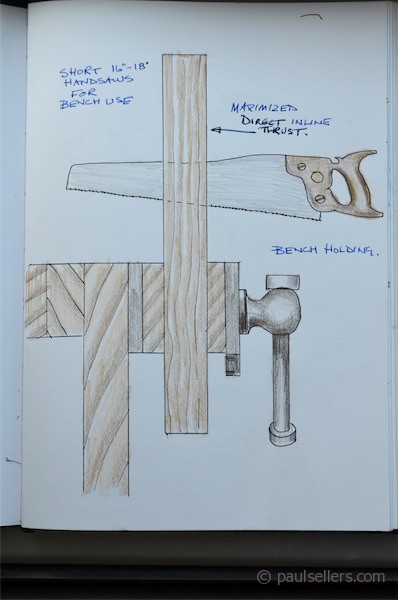

I think that what prompted these thoughts came as a result of my traveling from state to state. In my demo's I have been working with a 16” Disston handsaw I bought on eBay for £10 ($15 usd). When people see its effectiveness they seem quite amazed. I rip and crosscut with the same saw too and so they begin asking questions. The saw is short and so that makes the saw somewhat unusual, but I like its shortness for a couple of reasons. One, it’s compact length makes it ideal for traveling with and, two, it’s shortened punchiness gives the most inline directness that penetrates right at the heel of the saw. As an at-the-bench saw, where wood is anchored differently than say on saw horses, the presentation of the saw to the wood is more perpendicular and so has a directness other saws might not have. On sawhorses the saw is presented at an angle as with most overhand overhead cutting. That being the case, a short handsaw works well for vise work, whereas sawhorse cutting actually relies on the extra length, which gives good purchase over the material and extra length for those teeth lost in the longer cut with angled presentation of the saw to the wood because of the angle of the saw engaging within the actual cut in the wood being sawn. Short handsaws like mine are ideal for larger tenon work because when taper ground, the saw plate (blade) affords greater localized rigidity in front of and around the handle area of the saw and so a rigid back to the saw is not necessary. This then allows unlimited depth of cut to the saw.

Many of the modern saws used in woodworking today are actually well designed for certain spheres of woodworking and I use them quite frequently because of that. The saw in the photo above seems somewhat out of place in my tool chest and generally speaking, for me, it might be. In construction carpentry however it’s different and especially so in today's carpentry. Most carpenters rely on powered skill saws of one kind or another. These machines require accessibility to the wood and freedom of movement say across saw horses or the like. Sheet goods such as OSB, MDF, plywood and two-by stock is indeed mostly crosscut cutting (MDF excluded as it has no grain per se). That being the case, there are occasions throughout any day when the skill saw doesn’t reach and that’s when a handsaw with induction hardened teeth comes into its own. These saws will indeed crosscut dimensional lumber very effectively and also deal with pressed fibre board (chipboard UK) faced with plastic laminate, melamine and so on. Resins used as binding agents to create engineered boards like this are extremely hard on all saws too and so tungsten carbide teeth and induction hard-point teeth become essential.

Comments ()