More about your JOINERY knife

More on your knife.

Left handed knife

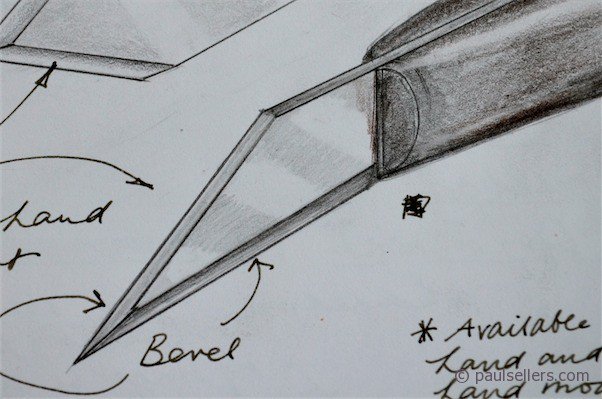

I hear often of left and right handed knives and how they aid vertical cutting in woodworking. In general that’s not altogether true. It’s a rare phenomenon that one person can use both hands with equal dexterity and exactness; that is, most of, left or right handed, cannot work using both hands capably with the same measure of accuracy, power and deliberation with our less dominant hand. It is actually far less problematic to adjust the work to task than use a knife or tool with only 10-20% efficiency. Paying $40 or £30 for a specialist knife such as a spear or diamond point knife means you must justify the price—trying to persuade someone that they wasted their money therefore become impossible. That said, there are times when you must use your less dominant hand, but that is quite rare. having said all of that, the benefit of a single knife blade capable of dealing with left and right hand cuts or working from the right and left side of a straight edge with the roll of a thumb has great appeal to the intellect, regardless of whether that works or not.

Inevitably the knife points above must be sharpened like these to gain a viable cutting edge and that is not much of an issue.

Using a sharp knife with my left (non dominant in my case) hand is like stirring my tea with my left hand. I can do it, but it feels awkward—now stirring is one thing. Now, as an experiment, try using a pair of scissors with the “other” hand or, even more difficult, try writing your name that way. Because someone invents something, we don’t have to fit our bodies to make it work.

It’s much easier, quicker, more accurate, controllable and powerful to train the dominant hand to task than the other. That being so, the conventional knife edge with twin bevels on opposite sides forming the same cutting edge enables both left and right-sided cuts with the same hand by simply compensating for the bevel of the knife. Most knives are 10-degrees, so it’s simply a question of tilting slightly as you cut and training your body to what it is naturally disposed to do. (no pun intended).

In woodworking we rarely use the knife for much more than severing the surface grain fibres to a depth of say 2mm or 1/16”. That being so, even if we are out of perpendicular by a further 10-degrees, it is unlikely that it will make any consequential difference or damage.

Almost all of our cuts are made against a straightedge, so as long as we angle the bevel into the straightedge, our surface cut line will show perfectly straight—usually we follow on with subsequent cuts with the chisel or saw—rarely with more knife cuts.

So what’s wrong with diamond or spear-point knives?

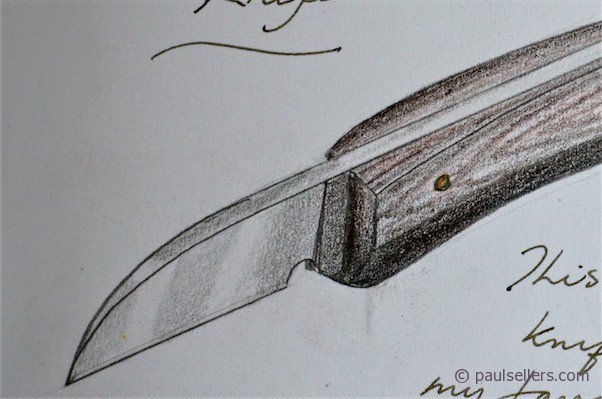

Spear-point knives make logical sense, yet in practice I find them awkward to use with left and right hand, which supposedly is the purpose of the design. If they were designed to be used by the two categories of people—left-and right-handed people, the design is perfect, but that is not the case. They are supposed to remove the need for two knives when in reality we never needed two knives to begin with and all of the craftsmen I ever knew never had but one knife. Also, the great assumption n all of this is the assumption that it’s purely a question of training your less dominant hand to use the device, but that’s not true at all, primarily because it is not necessary and therefore it becomes more impractical than practical. I have not met anyone yet who I saw use this knife with anywhere near equal alacrity and switched readily from left to right hand. I have however seen them switch their work to accommodate the dominant hand and arm constantly, which is what we do all day long every day without thinking. Inevitably again, spear point knives I have seen and used owned by other people almost always had the point missing or were corrected by rounding the point to a continuous edge as shown here.

Neat concept, highly impractical for something so intended to be, well, practical.

Comments ()