How to Build a Workbench – Leg Frame Glueing Up (part9)

NOTE:Just so you know, this is an older workbench series. Paul has a newer Workbench series. If you are interested in the updated version of Paul’s workbench please click the button down below. This page links to a cutting list, tools list, FAQS and much more.

Click here to go to the workbench page

Leg frame assembly and glue-up

Gluing up the leg frames comes next. If the joints are good and tight then they must be glued and left to dry for an hour or so, but even so, I prefer and suggest that you leave them overnight to completely glue-cure. With tight and large joints you must move quickly and be ready with a rubber headed hammer to drive the two together if need be. I have seen many joints ‘freeze’ mid glue-up in my five decades of working wood every day and combining clamping pressure with a hammer and block may be the only way to ‘unfreeze’ the surfaces inside the joint to fully seat the joint shoulders. This is more by way of a warning. It may not happen, but always have hammer and block at the ready just in case.

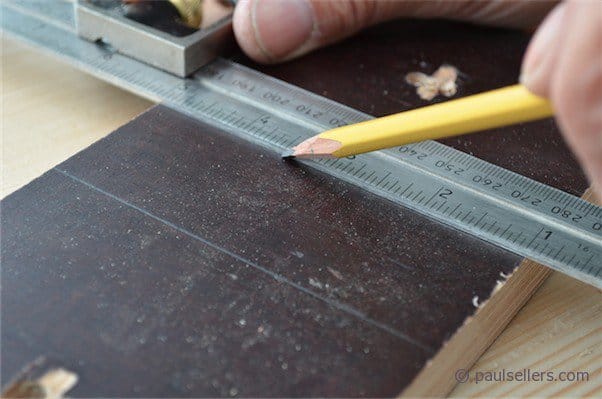

All of my joints snug together with the right amount of pressure on the cheeks. I sand my surfaces before I glue and so a dry run comes one time more just in case. This is my personal general practice because once glue hits wood I am in general at the point of no return. As a last plane step I take a flash shaving off all surfaces to remove pencil marks, grubby areas left from garden constructing a workbench and to prepare for the final stage, which is to sand the surfaces. Generally, I sand my surfaces because the hand planed surfaces are so smooth the finish will not take as well. That being so, I technically sand ‘rough’ rather than sand ‘smooth’. This sanding gives 'tooth' to the surfaces, an anchor for certain finishes to hold on to. But my sanding begins in general with 250-grit and ends there too. It's a brief encounter between wood and abrasive. I rarely use abrasive to create level or smooth surfaces in the way machinist woodworkers must. The #4 plane will get me where I need to be in general levelling and smoothing. Having planed all surfaces of the bench leg frame assembly and my dry runs completed I am ready for gluing up. I have all my clamps pre-set from my dry run. In many cases I run a bead of glue around the entrance rim of my mortise, to help ‘lubricate’ entry, which is a good tip, but in the case of the lower cross rail mortise and tenons I do not have this luxury because the protruding tenon would be smeared with glue. When the tenon lies flush, as with the top cross rail tenon, I can wipe off and plane the surface and flush the tenon so there is no trace of glue on any surface. You will need at least four sash clamps per leg frame assembly for this session. It’s worth having a couple of extras if you have them, just in case something needs some extra torque.

You must glue one side of the frame first; that is, you must glue the same ends of the top and bottom rails into the one leg and then do the opposite ends to receive the second leg. You will not be able to spread the legs should you glue up one rail to two legs. I mention it because it happens from time to time. Once a tenon goes together with a mortise it is often impossible to separate them. Use the rubber headed hammer or a regular hammer and block of wood to fully seat the joints as much as you can. With that done, apply the clamps, one to each side of each frame as shown. This will guarantee equal pressure from each side of the frame and to each shoulder. Use the hammer too. Even if the joint is seated I still add a couple of hammer blows to shock-seat the shoulders. It works.

Though it is almost impossible to make a frame like this out of square if the joints are well cut and shoulders square across and so on, it is possible to clamp a frame out of square. Check for square by measuring inside corner to inside corner. If the measurements are the same or within 1/8” (which means 1/16” out of square) there is no need to alter anything. If it is more, check that the clamps are parallel to the run of the rails. This can force a frame out of square and most often does, but people don’t realise it. Even if they are parallel, it is still possible to correct any out of squareness by adjust the clamps so that that they pull the longer distance into square. If your rails are the same length and the mortise holes dead parallel, and they should be if you followed the patterns and methods give, you will not have a problem. I give just-in-case solutions to help resolve possible issues ahead of time.

With both leg frames assembled you can add the bearer by gluing and screwing it to the rail and ends of the legs. On the standard leg frame assembly, pre drill the bearer with four 3/16” holes, run a zigzag of glue and secure with 2 ½” #12 screws. If you have made a leg frame to receive the tail vise simply screw the bearer to the tops of each leg with a single screw through each end. We then cut a block of 1 7/8” x whatever length we can to fit between the bearer and the top rail and the side of the vise screw mechanisms and the leg. This extends the support between the top rail and the bearer to reduce any flexing around this area. You can do this on either side of the vise screw mechanisms to shorten span distance to the underside of the benchtop, which minimises any flexing.

That is the leg frame assembly completed. Now we focus on the apron joinery.

Comments ()