More Flawed Concepts from FW

In the current Fine Woodworking Q&A section April 2012 the questioner asks a straightforward question about straightforward joinery with an angle for a chair he is making. He wants to know the best alignment of a mortise and tenon joint if the back of the chair is narrower than the front. The question is answered by a furniture maker, Jeff Miller, who I am afraid gave a very wrong answer that might knock many readers well off track. The heading immediately sets the tone and we have already seen that Fine Woodworking generally uses this to draw people into the article by sensationalising the headers. In this case the heading says:

"Angled Mortise is Better than Angled Tenon."

This seems like a minor opening statement, but it does preface the whole issue and, as it is said, 'he who frmes the issue determines the outcome" I see here that that outcome can be good, bad or indifferent. In this case I found it incomplete in discussing the surrounding issues that could have led to being much more informative and so I will try to address them to bring greater balance and prevent a flawed perspective.

I think it’s true to say that many woodworkers (amateur and professional) view this joint area as a conundrum, yet offset (angled) tenons are the norm at these interconnecting points and they have remained unchallenged for centuries simply because they work so very well. Jeff Miller says that, “An angled mortise and tenon is more difficult to make (the tenon has angled shoulders), but it is a better choice for two reasons.” Note the inference here is that the other type does not have angled shoulders. In reality, they both have angled shoulders at the shoulder line. He says that the tenon runs along the length, which is of course true. He says it makes it strong and the alternative is “weaker and prone to breaking.” This is like saying that an 8” x 8” post is weaker and more prone to breaking than a 10” x 10” post. The fact is that that is true. The fact is also true that neither of them will break under reasonable loads. I have in 48 years seen a several tenons broken, perhaps ten, but that’s out of thousands. In my own work I have never seen this type of tenon broken, but neither have I ever seen inline tenons used as a general practice. Most of the ten or tenons I have seen broken or broken myself have been on old tenons brought in for or during a restoration.

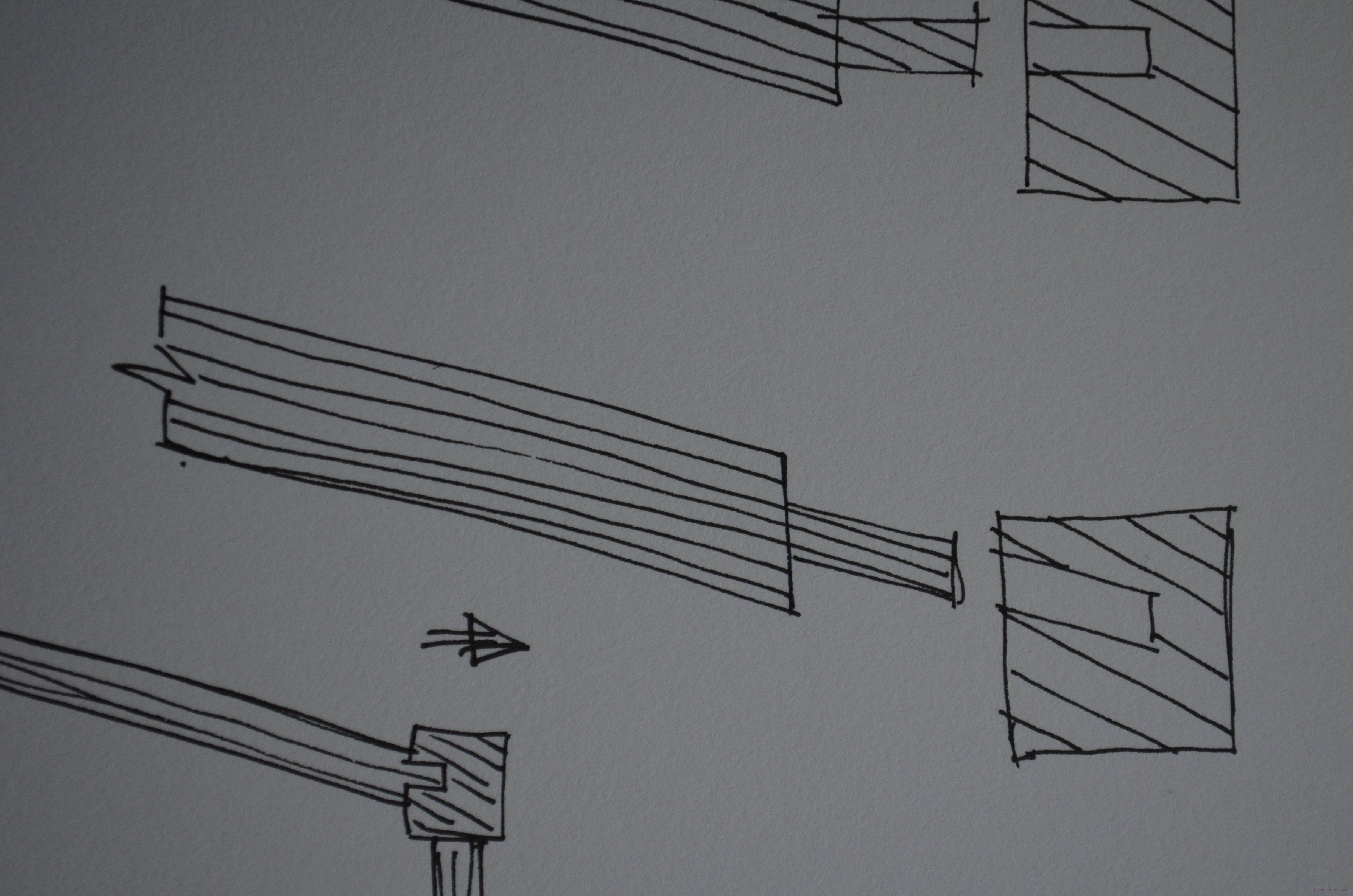

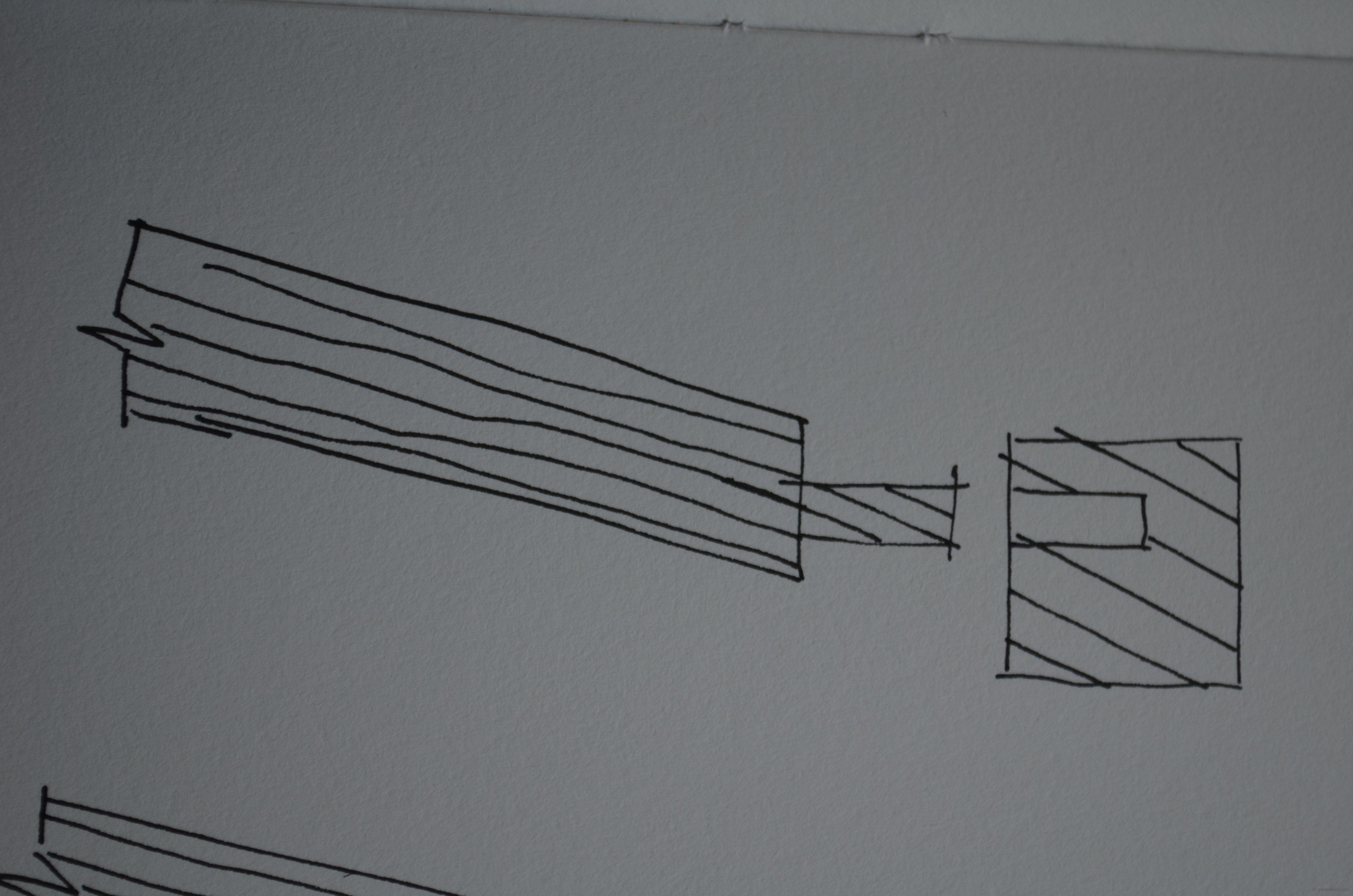

The most commonly used of joints used in chair construction where foursquare stock is used is angled tenons going into mortise holes parallel to the outside faces of the legs as shown here.

In general, no furniture is ever made with inline tenons for a couple of pivotal reasons Jeff Miller left out of the equation. One is that the method for cutting angled mortise holes demands the use of complex jigs if it is to be done by machine and is very difficult indeed to cut accurately by hand methods. It is also extremely difficult to clamp because the legs are now at an angle that must in some way be compensated for if standard clamps are to be used. I concede that strap clamps should work, but for the commonly used method using angled tenons you simply glue and assemble your sub-frames (front and back frames), set them to dry, and then add the side rails for a dry test fit before final gluing and assembly, which can be clamped very easily from front to back with straight clamps. Of the multiple millions of fully tenoned and mortised chairs created throughout Europe and North America, all of them are made with angled tenons and parallel mortise holes, not inline tenons as is suggested. I am fully persuaded that this method would have been tested and set aside time and time again. Had it proved a substantial improvement, someone would have adopted it, of that I am sure.

The second point he made is that the assembly is stronger. Is that true? I am not altogether sure, but one thing I am sure of is that the difference is only marginal and certainly not worth the very considerable effort it would take to actually make it work.

Another fact that Jeff Miller makes no mention of is that the mortise and tenon he espouses as being “more difficult to make but” the “better choice” is extremely scarce; so scarce I defy anyone to find this as an alternative in any craftsman’s workshop as a general-use procedure.

I hope that this reaches Bill Eckel of Lowell Mass. USA because I would suggest the standard method as the better of the two ways for him to go.

Comments ()