Sharpening on hollow stones

Someone emailed me as a result of my earlier post and said that if a stone hollowed through constant sharpening of the bevel of a tool’s cutting edge, how do you then hone the reverse flat side of the tool blade without creating a round face on what must be dead flat. That’s a good question. I had been working on the next stage of my challenge on sharpening methodology when I received the question and so my answer is here:

One answer is keep a second, superfine grit stone and use it only for flattening. This stone will still hollow (unless it’s a diamond plate), but only at a fraction of what it does when you hone the bevelled side of the tool. The other answer is to never hone the reverse side once it has been flattened and polished which is what I do. The reverse, (large flat surface) of my edge tools such as chisels, planes, spokeshaves and so on are lapped flat and then polished through refining stages to a mirror finish. This face never actually wears away. Remember it is not the bevel or the flat face that wears, but the very cutting edge. And even this is more a matter of edge fracture rather than wear. The finer (smaller) the edge the greater the edge-fracture because of the lack of back support. The reason we work so heavily on the bevel more than the flat is because it’s so much smaller than the whole of the flat face and therefore easier to maintain. We then move the whole bevel along the length of the blade until we remove the fracture on the very tip. The flat face is still highly polished and can be maintained in its polished state in the next stage in the sharpening process, which is honing on the strop.

Lapping the flat face of all the edge tools is critical to flatness straight off and this is something most woodworkers accept. I usually use my diamond stones for this, as they stay dead flat and wear so minimally I cannot detect any discrepancy resulting in roundedness. From here I go to a dead flat granite tile. A manufactured granite slab would of course be better, but it’s beyond the reach of most woodworkers when they are trying to get on with the job. I recommend that you take a straightedge into Home Depot or B&Q and look through the granite tiles until you find a flat one, or you buy a piece of thick plate or float glass around 5” wide and foot long. This will hold abrasive papers and will abrade the flat face of the edge tools dead flat. I usually work from 150-grit through to 1500-grit and then further polish the face up to the edge with abrasive car polish. In a few minutes my chisel is flat enough up to the edge and polished enough to give the surgically sharp tool edge I need for all of my work. From there I can work on the bevel in the usual manner, regardless of whether I use stones or plates. Here are the steps I use:

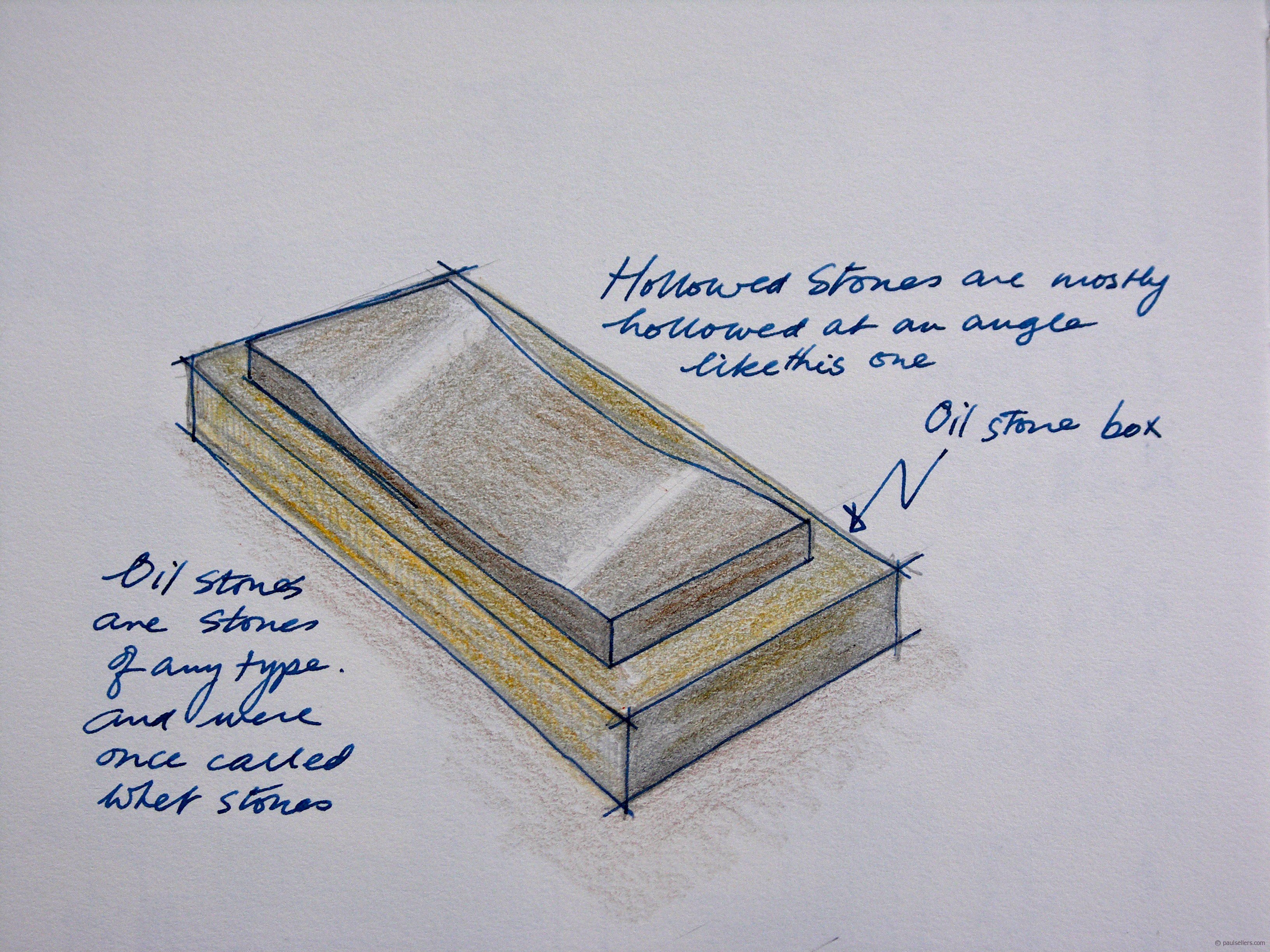

Here is a drawing of the shape of a well used and well worn whetstone (also known as oil stone natural stone, honing stone, Arkansas stone, India stone, carborundum stone, Japanese water stone, Norton stone and several more) of old. This is a stone used by working craftsmen and these are the ones I saw on all of the workbenches in the workshop where I grew up. No one ever flattened their stones that I ever knew and yet the men I worked with always had pristine sharpness that matched or exceeded what we have today.

From this point on it’s up to you what you do as to stone choice. They are all abrasive and they all cut steel. All of them work for woodworkers but some cut steel faster, resist wear more and they will all have different qualities to give you a sharpened edge.

I actually use diamond plates as I have for well over a decade. I recommend them because the stay flat, cut fast and last a very long time. I anticipate a diamond plate from EZE Lap or DMT (3" x 8") will last me for personal use about 20 years. Here at the school, sharpening 10 sets of chisel throughout the classes as well as ten planes, ten spokeshaves and other tools including all of my own every hour or two, they will last about 5-10 years.

For the bevel

Here is my preferred method. It’s not the only way, but it’s the fastest of all I know, apart from machine sharpening in commercial grinders, which no one has access to in general.

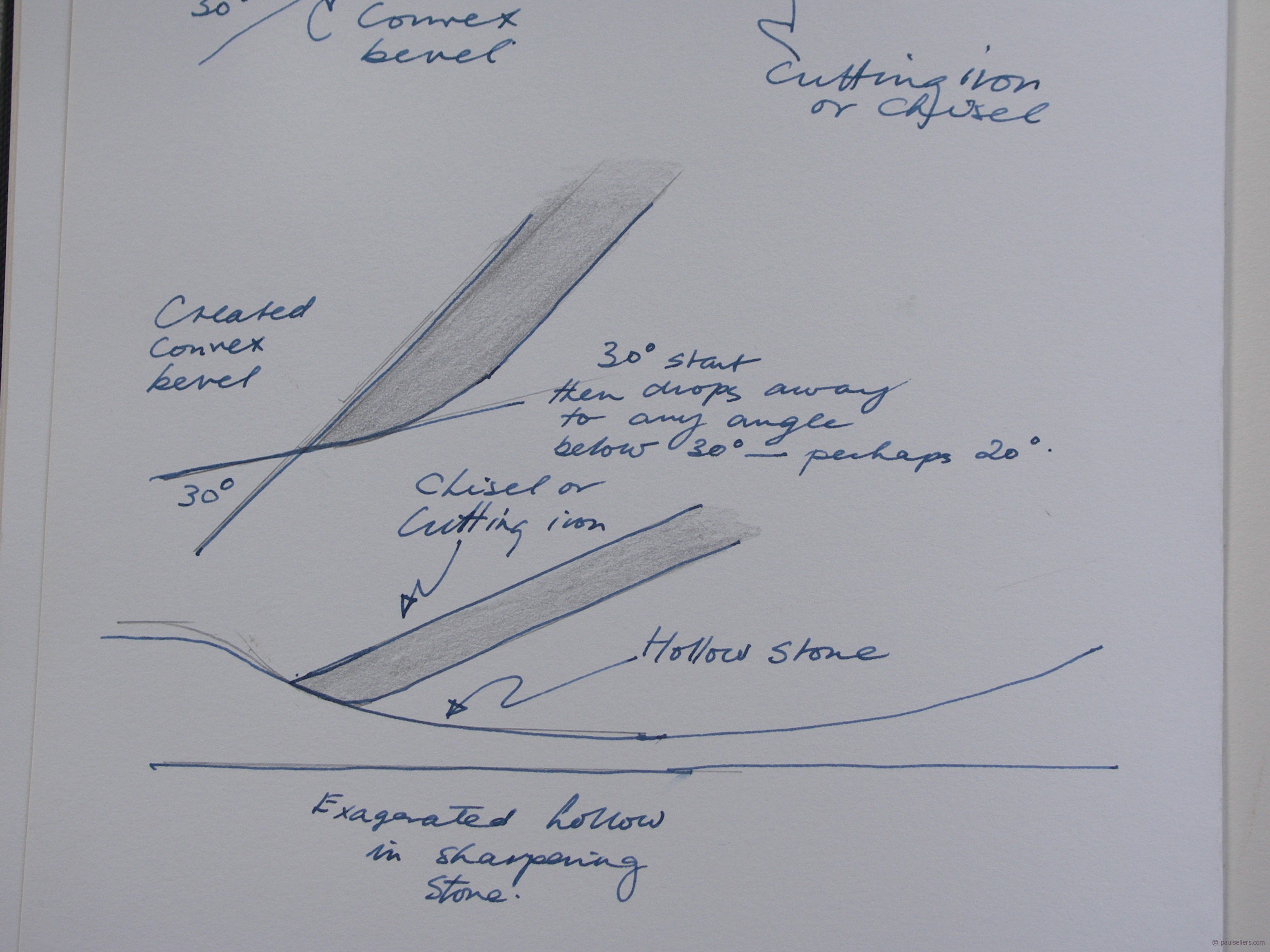

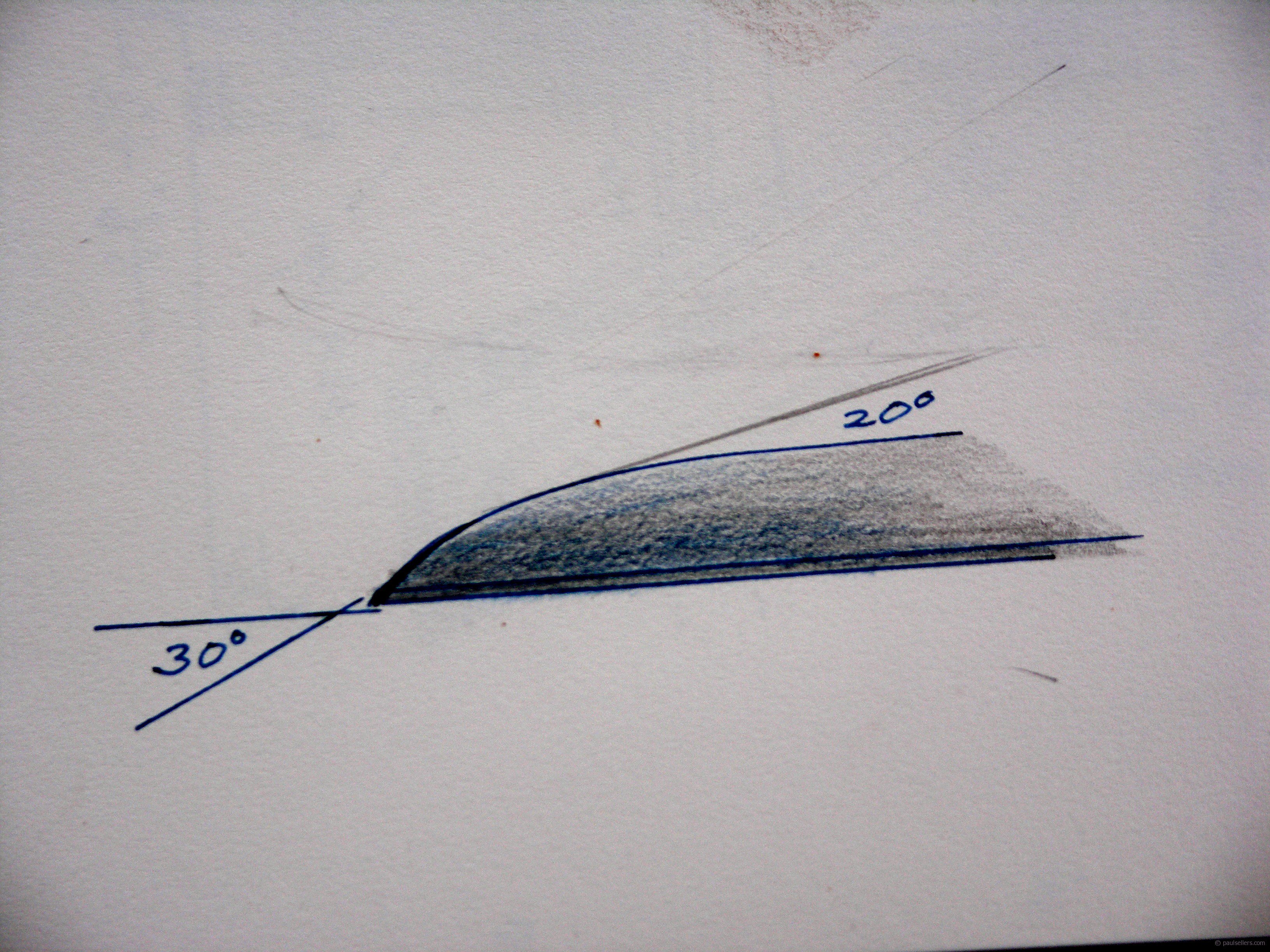

I have three 3" X 8” diamond plates in a row, Coarse (250-grit) on the left, fine in the centre (800-grit) and superfine on the right (1200-grit). I always go through every grit from coarse to superfine in that order. It’s important to maintain not restore. I abrade until I remove all previous polish and get down to the cutting edge to remove all dullness and edge fracture. I then go to through the next grits until I have an evenness on the entire convex bevel. You can push from the 30-degree angle and as you push forward gradually drop you hand at the far reach of the sharpening plate to cause an elliptical convex bevel. This will accomplish the convexing you want.

Strop

Now move to the strop. I use split cowhide, rough side uppermost, glued to a flat board 3” x 10” long. I charge the whole surface of the leather with buffing 15,000-grit compound. This polishes to the ideal level I need for most of my everyday work. Sometimes I go to higher levels and for this I have a square strop that can be flipped for 3 different grit size up to 25,000. The 4th side has plain leather for stropping without compound, to remove any burr from the edge.

The carrier fits in the vise and has a stop at each end so that I can pull the tool against the strop and the strop remains in place. The strop itself is not clamped by the vise but simply enclosed on the two long sides so without loosening the vise the strop can be lifted out, flipped and used with the different grit abrasive compound.

This is a long answer for a very simple solution. Don’t be put off. It takes minutes to do.

Pictures tomorrow

Comments ()